85 Understanding Bureaucracies and their Types

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the three different models sociologists and others use to understand bureaucracies

- Identify the different types of federal bureaucracies and their functional differences

Turning a spoils system bureaucracy into a merit-based civil service, while desirable, comes with a number of different consequences. The patronage system tied the livelihoods of civil service workers to their party loyalty and discipline. Severing these ties, as has occurred in the United States over the last century and a half, has transformed the way bureaucracies operate. Without the patronage network, bureaucracies form their own motivations. These motivations, sociologists have discovered, are designed to benefit and perpetuate the bureaucracies themselves.

watch it

Watch this video to learn more about the types of bureaucracies.

MODELS OF BUREAUCRACY

Bureaucracies are complex institutions designed to accomplish specific tasks. This complexity, and the fact that they are organizations composed of human beings, can make it challenging for us to understand how bureaucracies work. Sociologists, however, have developed a number of models for understanding the process. Each model highlights specific traits that help explain the organizational behavior of governing bodies and associated functions.

The Weberian Model

The classic model of bureaucracy is typically called the ideal Weberian model, and it was developed by Max Weber, an early German sociologist. Weber argued that the increasing complexity of life would simultaneously increase the demands of citizens for government services. Therefore, the ideal type of bureaucracy, the Weberian model, was one in which agencies are apolitical, hierarchically organized, and governed by formal procedures. Furthermore, specialized bureaucrats would be better able to solve problems through logical reasoning. Such efforts would eliminate entrenched patronage, stop problematic decision-making by those in charge, provide a system for managing and performing repetitive tasks that required little or no discretion, impose order and efficiency, create a clear understanding of the service provided, reduce arbitrariness, ensure accountability, and limit discretion.[1]

The Acquisitive Model

For Weber, as his ideal type suggests, the bureaucracy was not only necessary but also a positive human development. Later sociologists have not always looked so favorably upon bureaucracies, and they have developed alternate models to explain how and why bureaucracies function. One such model is called the acquisitive model of bureaucracy. The acquisitive model proposes that bureaucracies are naturally competitive and power-hungry. This means bureaucrats, especially at the highest levels, recognize that limited resources are available to feed bureaucracies, so they will work to enhance the status of their own bureaucracy to the detriment of others.

This effort can sometimes take the form of merely emphasizing to Congress the value of their bureaucratic task, but it also means the bureaucracy will attempt to maximize its budget by depleting all its allotted resources each year. This ploy makes it more difficult for legislators to cut the bureaucracy’s future budget, a strategy that succeeds at the expense of thrift. In this way, the bureaucracy will eventually grow far beyond what is necessary and create bureaucratic waste that would otherwise be spent more efficiently among the other bureaucracies.

The Monopolistic Model

Other theorists have come to the conclusion that the extent to which bureaucracies compete for scarce resources is not what provides the greatest insight into how a bureaucracy functions. Rather, it is the absence of competition. The model that emerged from this observation is the monopolistic model.

Proponents of the monopolistic model recognize the similarities between a bureaucracy like the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and a private monopoly like a regional power company or internet service provider that has no competitors. Such organizations are frequently criticized for waste, poor service, and a low level of client responsiveness. Consider, for example, the Bureau of Consular Affairs (BCA), the federal bureaucracy charged with issuing passports to citizens. There is no other organization from which a U.S. citizen can legitimately request and receive a passport, a process that normally takes several weeks. Thus there is no reason for the BCA to become more efficient or more responsive or to issue passports any faster.

There are rare bureaucratic exceptions that typically compete for presidential favor, most notably organizations such as the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the intelligence agencies in the Department of Defense. Apart from these, bureaucracies have little reason to become more efficient or responsive, nor are they often penalized for chronic inefficiency or ineffectiveness. Therefore, there is little reason for them to adopt cost-saving or performance measurement systems. While some economists argue that the problems of government could be easily solved if certain functions are privatized to reduce this prevailing incompetence, bureaucrats are not as easily swayed.

TYPES OF BUREAUCRATIC ORGANIZATIONS

A bureaucracy is a particular government unit established to accomplish a specific set of goals and objectives as authorized by a legislative body. In the United States, the federal bureaucracy enjoys a great degree of autonomy compared to those of other countries. This is in part due to the sheer size of the federal budget, approximately $3.5 trillion as of 2015.[2] And because many of its agencies do not have clearly defined lines of authority—roles and responsibilities established by means of a chain of command—they also are able to operate with a high degree of autonomy. However, many agency actions are subject to judicial review. In Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), the Supreme Court found that agency authority seemed limitless.[3] Yet, not all bureaucracies are alike. In the U.S. government, there are four general types: cabinet departments, independent executive agencies, regulatory agencies, and government corporations.

Cabinet Departments

There are currently fifteen cabinet departments in the federal government. Cabinet departments are major executive offices that are directly accountable to the president. They include the Departments of State, Defense, Education, Treasury, and several others. Occasionally, a department will be eliminated when government officials decide its tasks no longer need direct presidential and congressional oversight, such as happened to the Post Office Department in 1970.

Each cabinet department has a head called a secretary, appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. These secretaries report directly to the president, and they oversee a huge network of offices and agencies that make up the department. They also work in different capacities to achieve each department’s mission-oriented functions. Within these large bureaucratic networks are a number of undersecretaries, assistant secretaries, deputy secretaries, and many others. The Department of Justice is the one department that is structured somewhat differently. Rather than a secretary and undersecretaries, it has an attorney general, an associate attorney general, and a host of different bureau and division heads.

| Members of the Cabinet | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Year Created | Secretary as of January 2019 | Purpose |

| State | 1789 | Mike Pompeo | Oversees matters related to foreign policy and international issues relevant to the country |

| Treasury | 1789 | Steven Mnuchin | Oversees the printing of U.S. currency, collects taxes, and manages government debt |

| Justice | 1870 | Matthew Whitaker (acting attorney general) |

Oversees the enforcement of U.S. laws, matters related to public safety, and crime prevention |

| Interior | 1849 | David Bernhardt (acting) | Oversees the conservation and management of U.S. lands, water, wildlife, and energy resources |

| Agriculture | 1862 | Sonny Perdue | Oversees the U.S. farming industry, provides agricultural subsidies, and conducts food inspections |

| Commerce | 1903 | Wilbur Ross | Oversees the promotion of economic growth, job creation, and the issuing of patents |

| Labor | 1913 | Alex Acosta | Oversees issues related to wages, unemployment insurance, and occupational safety |

| Defense | 1947 | Patrick M. Shanahan (acting) | Oversees the many elements of the U.S. armed forces, including the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force |

| Health and Human Services | 1953 | Alex Azar | Oversees the promotion of public health by providing essential human services and enforcing food and drug laws |

| Housing and Urban Development | 1965 | Ben Carson | Oversees matters related to U.S. housing needs, works to increase homeownership, and increases access to affordable housing |

| Transportation | 1966 | Elaine Chao | Oversees the country’s many networks of national transportation |

| Energy | 1977 | Rick Perry | Oversees matters related to the country’s energy needs, including energy security and technological innovation |

| Education | 1980 | Betsy DeVos | Oversees public education, education policy, and relevant education research |

| Veterans Affairs | 1989 | Robert Wilkie | Oversees the services provided to U.S. veterans, including health care services and benefits programs |

| Homeland Security | 2002 | Kirstjen Nielsen | Oversees agencies charged with protecting the territory of the United States from natural and human threats |

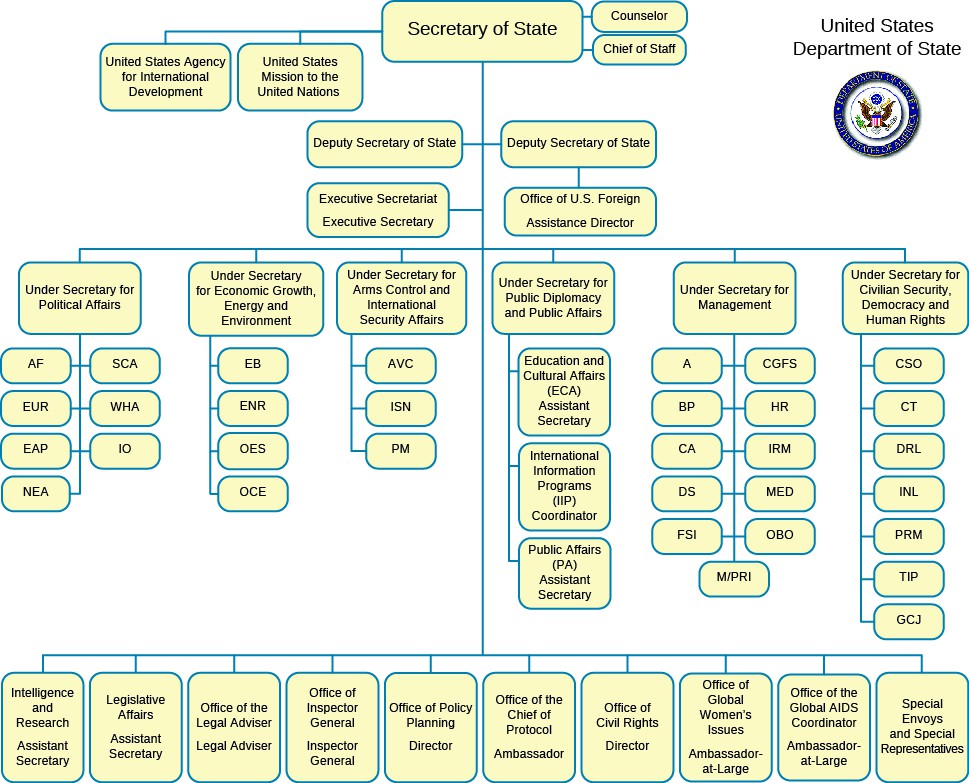

Individual cabinet departments are composed of numerous levels of bureaucracy. These levels descend from the department head in a mostly hierarchical pattern and consist of essential staff, smaller offices, and bureaus. Their tiered, hierarchical structure allows large bureaucracies to address many different issues by deploying dedicated and specialized officers. For example, below the secretary of state are a number of undersecretaries. These include undersecretaries for political affairs, for management, for economic growth, energy, and the environment, and many others. Each controls a number of bureaus and offices. Each bureau and office in turn oversees a more focused aspect of the undersecretary’s field of specialization. For example, below the undersecretary for public diplomacy and public affairs are three bureaus: educational and cultural affairs, public affairs, and international information programs. Frequently, these bureaus have even more specialized departments under them. Under the bureau of educational and cultural affairs are the spokesperson for the Department of State and his or her staff, the Office of the Historian, and the United States Diplomacy Center.[4]

LINK TO LEARNING

Created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to help manage the growing responsibilities of the White House, the Executive Office of the President still works today to “provide the President with the support that he or she needs to govern effectively.”

Independent Executive Agencies and Regulatory Agencies

Like cabinet departments, independent executive agencies report directly to the president, with heads appointed by the president. Unlike the larger cabinet departments, however, independent agencies are assigned far more focused tasks. These agencies are considered independent because they are not subject to the regulatory authority of any specific department. They perform vital functions and are a major part of the bureaucratic landscape of the United States. Some prominent independent agencies are the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which collects and manages intelligence vital to national interests, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), charged with developing technological innovation for the purposes of space exploration, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which enforces laws aimed at protecting environmental sustainability.

An important subset of the independent agency category is the regulatory agency. Regulatory agencies emerged in the late nineteenth century as a product of the progressive push to control the benefits and costs of industrialization. The first regulatory agency was the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), charged with regulating that most identifiable and prominent symbol of nineteenth-century industrialism, the railroad. Other regulatory agencies, such as the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which regulates U.S. financial markets and the Federal Communications Commission, which regulates radio and television, have largely been created in the image of the ICC. These independent regulatory agencies cannot be influenced as readily by partisan politics as typical agencies and can therefore develop a good deal of power and authority. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) illustrates well the potential power of such agencies. The SEC’s mission has expanded significantly in the digital era beyond mere regulation of stock floor trading.

Government Corporations

Agencies formed by the federal government to administer a quasi-business enterprise are called government corporations. They exist because the services they provide are partly subject to market forces and tend to generate enough profit to be self-sustaining, but they also fulfill a vital service the government has an interest in maintaining. Unlike a private corporation, a government corporation does not have stockholders. Instead, it has a board of directors and managers. This distinction is important because whereas a private corporation’s profits are distributed as dividends, a government corporation’s profits are dedicated to perpetuating the enterprise. Unlike private businesses, which pay taxes to the federal government on their profits, government corporations are exempt from taxes.

The most widely used government corporation is the U.S. Postal Service. Once a cabinet department, it was transformed into a government corporation in the early 1970s. Another widely used government corporation is the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, which uses the trade name Amtrak. Amtrak was the government’s response to the decline in passenger rail travel in the 1950s and 1960s as the automobile came to dominate. Recognizing the need to maintain a passenger rail service despite dwindling profits, the government consolidated the remaining lines and created Amtrak.[5]

THE FACE OF DEMOCRACY

Those who work for the public bureaucracy are nearly always citizens, much like those they serve. As such they typically seek similar long-term goals from their employment, namely to be able to pay their bills and save for retirement. However, unlike those who seek employment in the private sector, public bureaucrats tend to have an additional motivator, the desire to accomplish something worthwhile on behalf of their country. In general, individuals attracted to public service display higher levels of public service motivation (PSM). This is a desire most people possess in varying degrees that drives us to seek fulfillment through doing good and contributing in an altruistic manner.[6]

Dogs and Fireplugs

In Caught between the Dog and the Fireplug, or How to Survive Public Service (2001), author Kenneth Ashworth provides practical advice for individuals pursuing a career in civil service.[7] Through a series of letters, Ashworth shares his personal experience and professional expertise on a variety of issues with a relative named Kim who is about to embark upon an occupation in the public sector. By discussing what life is like in the civil service, Ashworth provides an “in the trenches” vantage point on public affairs. He goes on to discuss hot topics centering on bureaucratic behaviors, such as (1) having sound etiquette, ethics, and risk aversion when working with press, politicians, and unpleasant people; (2) being a subordinate while also delegating; (3) managing relationships, pressures, and influence; (4) becoming a functional leader; and (5) taking a multidimensional approach to addressing or solving complex problems.

Ashworth says that politicians and civil servants differ in their missions, needs, and motivations, which will eventually reveal differences in their respective characters and, consequently, present a variety of challenges. He maintains that a good civil servant must realize he or she will need to be in the thick of things to provide preeminent service without actually being seen as merely a bureaucrat. Put differently, a bureaucrat walks a fine line between standing up for elected officials and their respective policies—the dog—and at the same time acting in the best interest of the public—the fireplug.

In what ways is the problem identified by author Kenneth Ashworth a consequence of the merit-based civil service?

Bureaucrats must implement and administer a wide range of policies and programs as established by congressional acts or presidential orders. Depending upon the agency’s mission, a bureaucrat’s roles and responsibilities vary greatly, from regulating corporate business and protecting the environment to printing money and purchasing office supplies. Bureaucrats are government officials subject to legislative regulations and procedural guidelines. Because they play a vital role in modern society, they hold managerial and functional positions in government; they form the core of most administrative agencies. Although many top administrators are far removed from the masses, many interact with citizens on a regular basis.

Given the power bureaucrats have to adopt and enforce public policy, they must follow several legislative regulations and procedural guidelines. A regulation is a rule that permits government to restrict or prohibit certain behaviors among individuals and corporations. Bureaucratic rulemaking is a complex process that will be covered in more detail in the following section, but the rulemaking process typically creates procedural guidelines, or more formally, standard operating procedures. These are the rules that lower-level bureaucrats must abide by regardless of the situations they face.

Elected officials are regularly frustrated when bureaucrats seem not follow the path they intended. As a result, the bureaucratic process becomes inundated with red tape. This is the name for the procedures and rules that must be followed to get something done. Citizens frequently criticize the seemingly endless networks of red tape they must navigate in order to effectively utilize bureaucratic services, although these devices are really meant to ensure the bureaucracies function as intended.

Summary

To understand why some bureaucracies act the way they do, sociologists have developed a handful of models. With the exception of the ideal bureaucracy described by Max Weber, these models see bureaucracies as self-serving. Harnessing self-serving instincts to make the bureaucracy work the way it was intended is a constant task for elected officials. One of the ways elected officials have tried to grapple with this problem is by designing different types of bureaucracies with different functions. These types include cabinet departments, independent regulatory agencies, independent executive agencies, and government corporations.

Try It

Glossary

- Government Corporation

- a corporation that fulfills an important public interest and is therefore overseen by government authorities to a much larger degree than private businesses

- Red Tape

- the mechanisms, procedures, and rules that must be followed to get something done

- Susan J. Hekman. 1983. "Weber’s Ideal Type: A Contemporary Reassessment". Polity 16 No. 1: 119–37. ↵

- Congressional Budget Office Report, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44172 (June 6, 2016). ↵

- A. L. A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935). ↵

- http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/rls/dos/436.htm (June 6, 2016). ↵

- David C. Nice. 1998. Amtrak: the history and politics of a national railroad. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. ↵

- James L. Perry. 1996. "Measuring Public Service Motivation: An Assessment of Construct Reliability and Validity." Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 6, No. 1: 5–22. ↵

- Kenneth H. Ashworth. 2001. Caught Between the Dog and the Fireplug, or, How to Survive Public Service. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ↵