4 5.5 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation

One important area of primary research undertaken when embarking on any large scale project entails “public engagement,” or stakeholder consultation. Public engagements is the broadest term used to describe the increasingly necessary process that companies, organizations, and governments must undertake to achieve a “social licence to operate.” Stakeholder engagement can range from simply informing the public about plans for a project, to engaging in more consultative practices like getting input and feedback from various groups, and even to empowering key community stakeholders in the final decision-making process.

For projects that have social, economic, and environmental impacts, stakeholder consultation is an increasingly critical part of the planning stage. Creating an understanding of how projects will affect a wide variety of stakeholders is beneficial for both the company instigating the project and the people who will be affected by it. Listening to stakeholder feedback and concerns can be helpful in identifying and mitigating risks that could otherwise slow down or even derail a project. For stakeholders, the consultation process creates an opportunity to be informed, as well as to inform the company about local contexts that may not be obvious, to raise issues and concerns, and to help shape the objectives and outcomes of the project.

What is a Stakeholder?

Stakeholders include any individual or group who may have a direct or indirect “stake” in the project – anyone who can be affected by it, or who can have an effect on the actions or decisions of the company, organization or government. They can also be people who are simply interested in the matter, but more often they are potential beneficiaries or risk-bearers. They can be internal – people from within the company or organization (owners, managers, employees, shareholders, volunteers, interns, students, etc.) – and external, such as community members or groups, investors, suppliers, consumers, policy makers, etc. Increasingly, arguments are being made for considering non-human stakeholders such as the natural environment.[1]

Stakeholders can contribute significantly to the decision-making and problem-solving processes. People most affected by the problem and most directly impacted by its effects can help you

- understand the context, issues and potential impacts

- determine your focus, scope, and objectives for solutions

- establish whether further research is needed into the problem.

People who are attempting to solve the problem can help you

- refine, refocus, prioritize solution ideas and

- define necessary steps to achieving them

- implement solutions, provide key data, resources, etc.

There are also people who could help solve the problem, but lack awareness of the problem or their potential role. Consultation processes help create the awareness of the project to potentially get these people involved during the early stages of the project.

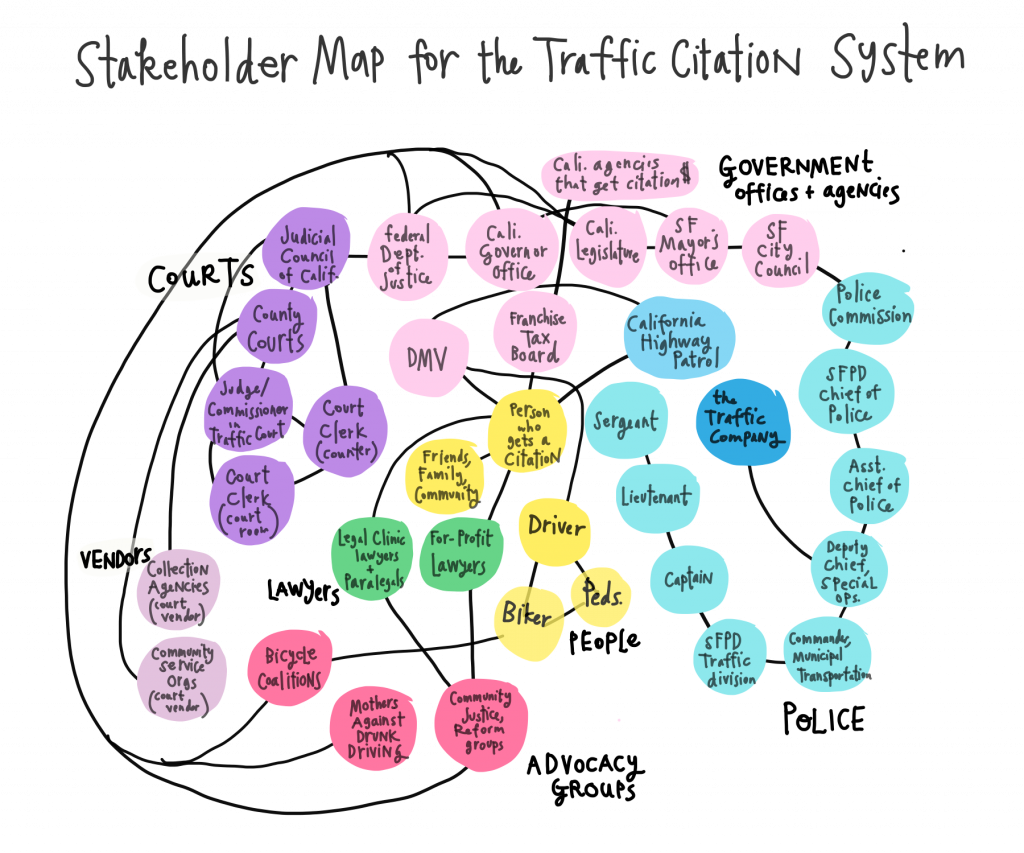

Stakeholder Mapping

The more a stakeholder group will be materially affected by the proposed project, the more important it is for them to be identified, properly informed, and encourage to participate in the consultation process. It is therefore critical to determine who the various stakeholders are, as well as their level of interest in the project, the potential impact it will have on them, and power they have to shape the process and outcome. You might start by brainstorming or mind-mapping all the stakeholders you can think of. See Figure 5.5.1 as an example.

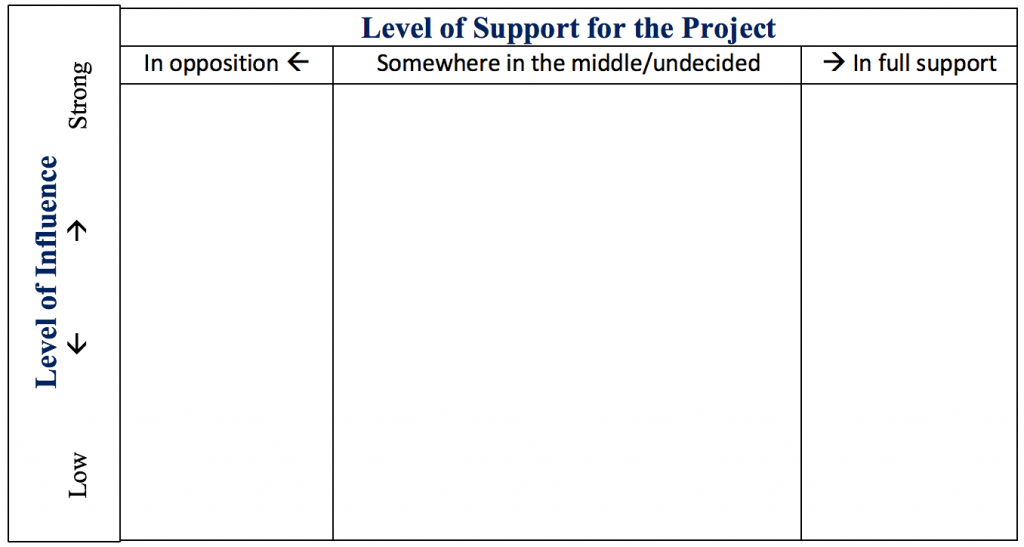

Once you have identified stakeholders who may be impacted, organize them into categories or a matrix. One standard method of organizing stakeholders is to determine which are likely to be in support of the project and which are likely to oppose it, and then determine how much power or influence each of those groups has (see Figure 5.5.2). For example, a mayor of a community has a strong level of influence. If the mayor is in full support of the project, this stakeholder would go in the top right corner of the matrix. Someone who is deeply opposed to the project, but has little influence or power, would go at the bottom left corner.

A matrix like this can help you determine what level of engagement is warranted: where efforts to “consult and involve” might be most needed and most effective, or where more efforts to simply “inform” might be most useful. You might also consider the stakeholders’ level of knowledge on the issue, level of commitment (whether in support or opposed), and resources available.

Levels of Stakeholder Engagement

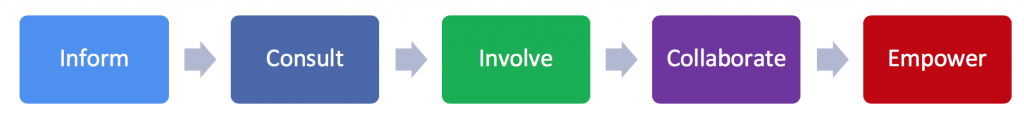

There are various levels of engagement, ranging from simply informing people about what you plan to do to actively seeking consent and placing the final decision in their hands. This range, presented in Figure 5.5.3, is typically presented as a “spectrum” or continuum of engagement from the least to most amount of engagement with stakeholders.

Depending on the type of project, the potential impacts and the types and needs of stakeholders, you may engage in a number of levels and strategies of engagement across this spectrum using a variety of different tools (see Table 5.5.1):

- Inform: Provide stakeholders with balanced and objective information to help them understand the project, the problem, and the solution alternatives. (There is no opportunity for stakeholder input or decision-making.)

- Consult: Gather feedback on the information given. Level of input can range from minimal interaction (online surveys, etc) to extensive. Can be a one-time or ongoing/iterative opportunities to give feedback to be considered in the decision-making process)

- Involve: Work directly with stakeholders during the process to ensure that their concerns and desired outcomes are fully understood and taken into account. Final decisions are still made by the consulting organization, but with well-considered input from stakeholders.

- Collaborate: Partner with stakeholders at each stage of the decision-making, including developing alternative solution ideas and choosing the preferred solution together. Goal is to achieve consensus regarding decisions.

- Empower: Place final decision-making power in the hands of stakeholders. Voting ballots and referenda are common examples. This level of stakeholder engagement is rare and usually includes a small number of people who represent important stakeholder groups.

| Inform | Consult | Involve / Collaborate / Empower |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Consultation Project Management Steps

There is no single “right” way of consulting with stakeholders. Each situation will be different so each consultation process will be context-specific and will require a detailed plan. A poorly planned consultation process can backfire as it can lead to a lack of trust between stakeholders and the company. Therefore, it is critical that the process be carefully mapped out in advance, and that preliminary work is done to determine the needs and goals of the process and the stakeholders involved. In particular, make sure that whatever tools you choose to use are fully accessible to all the stakeholders you plan to consult; an online survey is not much use to a community that lacks robust wifi infrastructure. Consider the following steps:

- Situation Assessment: Who needs to be consulted about what and why? Define internal and external stakeholders, determine their level of involvement, interest level, and potential impact, their needs and conditions for effective engagement.

- Goal-setting: What is your strategic purpose for consulting with stakeholders at this phase of the project? Define clear understandable goals and objectives for the role of stakeholders in the decision making process. Determine what questions, concerns, and goals the stakeholders will have and how these can be integrated into the process.

- Planning/Requirements: Based on situation assessment and goals, determine what engagement strategies to use and how to implement them to best achieve these goals. Ensure that strategies consider issues of accessibility and inclusivity and consider vulnerable populations. Consider legal or regulatory requirements, policies, or conditions that need to be met. Determine how you will collect, record, track, analyze and disseminate the data.

- Process and Event Management: keep the planned activities moving forward and on-track, and adjust strategies as needed. Keep track of documentation.

- Evaluation: Design an evaluation metric to gauge the success of the engagement strategies; collect, analyze, and act on the data collected throughout the process. Determine how will you report the results of engagement process back to the stakeholders.

Effective communication is the foundation of stakeholder consultation. The ability to create and distribute effective information, develop meaningful relationships, build trust, and listen to public input is essential. The basic communication skills required for any successful stakeholder engagement project include:

- Effective Writing: The ability to create clear and concise written messages in plain language.

- Visual Rhetoric: The ability to combine words and graphics to make complex issues understandable to a general audience.

- Public Speaking/Presenting: The ability to present information to large audiences in a comfortable and understandable way. The ability to create effective visual information that assists the audience’s understanding.

- Interpersonal and intercultural skills: The ability to relate to people in face-to-face situations, to make them feel comfortable and secure, and to be mindful of cultural factors that may affect interest level, accessibility, impact, values, or opinions.

- Active listening: The ability to focus on the speaker and portray the behaviors that provide them with the time and safety needed to be heard and understood. The ability to report back accurately and fully what you have heard from participants.

Additional Resources

For more information regarding consulting with Indigenous peoples and considering gender, with specific case study examples, see Clennan’s “Stakeholder Consultation” (.pdf). [3] The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also has an online “Public Participation Guide.”[4] For a recent and local example of a stakeholder engagement plan, see the University of Victoria’s “Campus Greenway Engagement Plan.”[5] A significant step in this plan — a Design Charrette — was implemented in the fall of 2018; the results of that engagement activity, presented in a Summary Report (.pdf) [6] resulted in changes and augmentation of the original plan based on stakeholder feedback.

- C. Driscoll and M. Starik, “The primordial stakeholder: Advancing the conceptual consideration of stakeholder status for the natural environment,” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 49, no. 1, 2004, pp. 55-73. Available: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000013852.62017.0e ↵

- M. Hagan, “Stakeholder mapping of traffic ticket system,” Open Law Lab [Online] Aug. 28, 2017. Available: http://www.openlawlab.com/2017/08/28/stakeholder-mapping-the-traffic-ticket-system/ . CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.[Accessed Feb 24, 2019]. ↵

- R. Clennan, “Part 1: Stakeholder Consultation IFC,” [Online .pdf]. Available: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/5a4e740048855591b724f76a6515bb18/PartOne_StakeholderConsultation.pdf?MOD=AJPERES April 24, 2007. [Accessed Feb. 24, 2019]. ↵

- EPA, “Public Participation Guide: View and Print Version,” United States Environmental Protection Agency [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/public-participation-guide-view-and-print-versions [Accessed Feb. 24, 2019]. ↵

- University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability, “Engagement plan for: The University of Victoria Grand Promenade landscape plan and design guidelines,” Campus Greenway [Online]. Available: https://www.uvic.ca/campusplanning/current-projects/campusgreenway/index.php ↵

- University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability, "The Grand Promenade Design Charrette: Summary Report 11.2018," Campus Greenway [Online]. Available: https://www.uvic.ca/campusplanning/current-projects/campusgreenway/index.php ↵