Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

6 Introduction to Four-Part Harmony and Voice Leading

Key Points

- Four-Part Harmony is the study and application of tonality through harmonic progressions in four voices (parts).

- This introductory chapter builds upon what we learned in species counterpoint (chapters covered in the section on Modal Counterpoint). Among new concepts introduced are:

- The four parts in SATB chorale style:

- Basic guidelines for both the spacing and voicing of chords

- Voicing is the process of taking a given chord and assigning/arranging the chord tones to each of the four voices (parts)

- Good spacing helps to insure balance and homogenous blending of the harmony.

- There are two different types of spacing: (closed and open).

- The voices, while sounding a complete chord, are also to be considered as independent lines, much like we learned in our study of counterpoint, and the process of moving the voices from one chord to the next is called voice leading.

- As with our study of counterpoint, the study of harmony in four part SATB chorale style is not designed to create good music but rather develop skills and reenforce basic musical concepts through active learning and creation, as well as to serve as a foundation upon which to build further knowledge. These exercises are analogous to lifting weights as part of athletic training, or the study of calculus as part of training in engineering, etc. Thus, these exercises in and of themselves are not intended to produce anything close to finished songs or well-constructed compositions. However, and what is an important challenge, one should strive to make them as musical as possible within the limited guidelines and resources provided.

Philosophy and Application

Pedagogical (Teaching) Philosophy

As with counterpoint, one might ask why we engage actively in something as strict and even as antiquated in some respects as four part harmony in SATB chorale style? The answer to such a question is similar to the answer given for why we engage in strict counterpoint exercises: These are directed studies in skill and knowledge building. I often use analogies from the world of sport. Larry Bird, for example, is one of the greatest basketball players of all time. However, Bird didn’t become an NBA legend simply by being born with great basketball skills. In fact, Bird was, by nearly every physical metric except for his height (he was 6′ 10″) a gangly, awkward and rather unsuited person for the game of basketball as compared to many other (for example, peers like the great Ervin “Magic” Johnson who was far more physically gifted). However, Bird worked hard at his craft for hours on end and built up his body with daily rigourous exercise. Any pro basketball player spends countless hours in the gym working with weights, engaging in stretches and sustained aerobic exercise, etc., all of which we don’t see directly on the court but is manifest in the ability of the athlete to perform at a high level during a game. Similarly, engaging in activities such as counterpoint or harmony exercises, even in the most dogmatic of approach as sometimes given here, are to the musician, composer, and songwriter as to the athlete engaging in daily gym work. These exercises are not intended to be efforts at great original composition but are rather designed to develop skills and hone a sense of form, control, and craft, furthering knowledge, understanding, and musicianship.

What is Four Part Harmony?

In four (4) part writing we think vertically, in the domain of harmony, voicing chords into four distinct parts. These four parts will be referred to as “voices”, and we will first work within in a format known as “chorale” or SATB style. The four parts are labeled by their range, from highest to lowest: Soprano (S), Alto (A), Tenor (T), and Bass (B). We will also consider how chords move and connect to one another, forming a harmonic progression (also known as a chord progression) and defining a complete musical idea known as a phrase. The challenge is to create or realize musical phrases in the four parts that are both harmonically coherent and logical within the key in which the phrase is written, and are melodically coherent and satisfying through a process and concept we call voice leading.

As with our first exercises in counterpoint, and to keep things simple and focused on only a few elements at a time, our beginning exercises in four-part harmony will not be concerned with rhythm and, as such, we will not worry about a time signature or any type of meter. The only note value we will use will use at first will be the whole note.

The Four Voices: Soprano (S), Alto (A), Tenor (T), Bass (B)

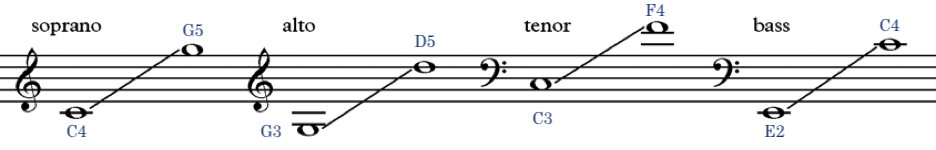

Each voice (part) is considered as an independent musical line, having an independent range defined by an upper note and a lower note. When writing in SATB “Chorale” Style, you should avoid exceeding these ranges. Although the terms we use to define each voice (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) have their origins in choral music, these ranges only loosely relate to actual human vocal ranges often found in a choir (professional choirs will often have greater flexibility in terms of range). The ranges assigned in SATB style are approximate and used in a very general manner. The ranges of each voice are show in Example 1 below.

Example 1. The ranges of each voice in four-voice SATB style

Example 1. The ranges of each voice in four-voice SATB style

Voicing, Spacing, and Doubling

Voicing is a term we use to describe how a given chord is arranged (distributed) across each part. In general, there are many ways in which we might be able to voice a chord and the two primary considerations are how many notes a chord has, and how many voices (parts) are available for use.

Answering both considerations, as introduced above, in SATB chorale style, we will have four voices with which we may assign the notes from any given chord. And, for the time being, we will be working with purely diatonic triads and thus all of the chords available will be made up of three distinct tones, expressed in pitch-classes. As you will recall from our Basic Musicianship study (you may further review in fundamentals), the chord tones for any triad are labeled as follows: root, third, and fifth. Therefore, when we voice a triad, we are assigning each of the three chord tones to the four available voices. This process is, in fact, a very simple form of arranging and orchestration (more of which will be covered in later chapters). You may well ask how we will deal with a three note chord using four voices and this is covered in depth below.

In terms of music notation, our SATB parts will be written on a grand staff, with the soprano and alto parts written on the upper staff (treble) and the tenor and bass written on the lower staff (bass clef). This will be very similar to how we wrote our counterpoint exercises using one staff, but representing two voices on that staff. As with counterpoint, even though we will be writing two voices on one staff, we will still consider each part a a separate line. Later, when we begin using note values that require use of a stem (i.e. half-notes, quarter-notes, and so on), we will differentiate each line as we did in second and fourth species counterpoint by using the notation convention where the stems are in opposite directions: In the treble staff the soprano will always be shows as stems up and the alto as stems down, and in our bass staff the tenor will be shown as stems up and the bass as stems down. This allows us to easily see each part individually.

Voicing Guidelines

- When we voice triads, we need to make sure that each chord tone of the triad is represented. As a result, no chord tones are to be omitted at this time.

- For now we will be working only with triads in root position. A root position chord has the root sounding in the lowest voice and, thus, in SATB texture, we will assign the root to the bass voice. The upper three voices of soprano, alto, and tenor are free to take whichever chord tones are remaining as long as we respect the spacing guidelines above. Later we will learn how to work with inversions.

- Doubling: Since a triad only contains three distinct tones and we have four voices, one of the voices will be free to double: that is, one of the chord tones will be represented twice in the SATB texture. In our first exercises, we will only double the root of the triad. Later we will learn how and when it is possible and even desirable to double other chord tones.

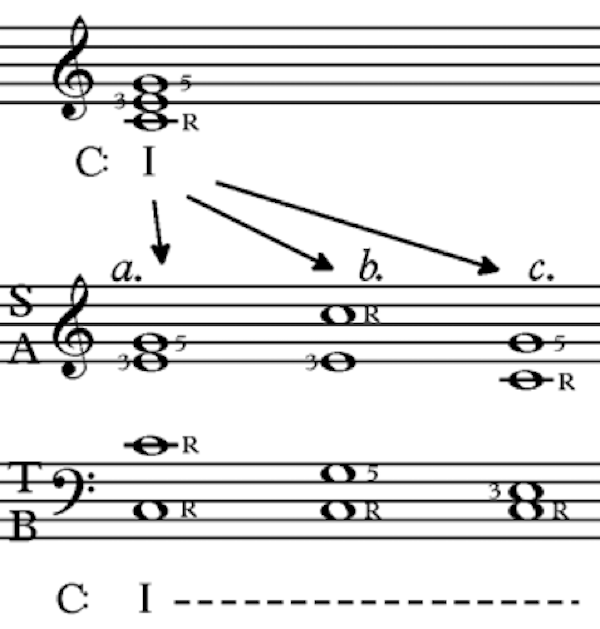

The example below shows three possible root position voicings of a C major triad in a SATB texture:

Example 2. A C major triad voiced three ways (a, b, c) in SATB texture. R = root, 3 = third, 5 = fifth

Voice Spacing in SATB Chorale Texture

While we must always consider the ranges of each voice part in SATB chorale style, we will also need to consider the vertical spacing (interval distance) between each of the voices. This will be similar to how we considered the spacing of the voices in our counterpoint assignments, being mindful of how far apart the counterpoint melody and cantus firmus are at any given moment. Since we now have four voices to consider, there are a few more considerations:

- Upper Three Voices (Soprano, Alto, Tenor): Each of the upper three voices may not exceed the distance of one octave between any adjacent voice. In other words, the Soprano to Alto distance should not exceed an octave, and the Alto to Tenor distance should not exceed an octave. Both conditions must be true.

- Bass to Tenor: The bass voice, by virtue of its position as the lowest voice of the harmony, has a bit more freedom and, as a result, may exceed the distance of an octave in relationship to its neighboring voice the tenor. However, this distance may not exceed that of a twelfth (an octave plus a fifth).

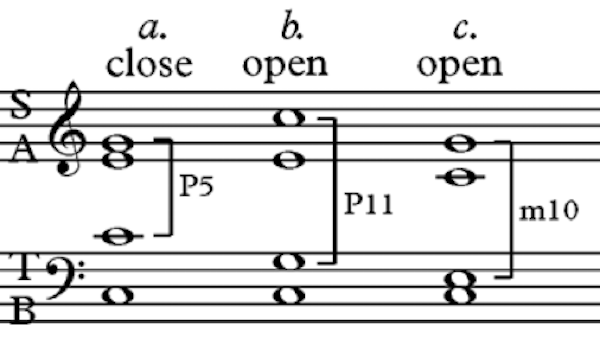

When looking at any chord voicing as a whole, taking into account all of the voices, we have two ways of describing the spacing: close and open.

Close Position (spacing): The upper voices, without the bass note considered, are an octave or less apart in total distance. In SATB texture, we measure that distance between the Soprano and Tenor voices.

Open Position (spacing): The upper voices, without the bass note considered, exceed an octave in total distance.

The example below shows how we would describe the spacing of the three voicings of a C major triad as shown in Example 2:

Example 3. Open or Close spacing positions for each chord (a, b, and c respectively) as found in Example 2

Roman Numerals and Labeling of Chords

In SATB chorale style, we will label each phrase with the primary key in which the phrase operates and each chord in terms of its function in the key, type and quality.

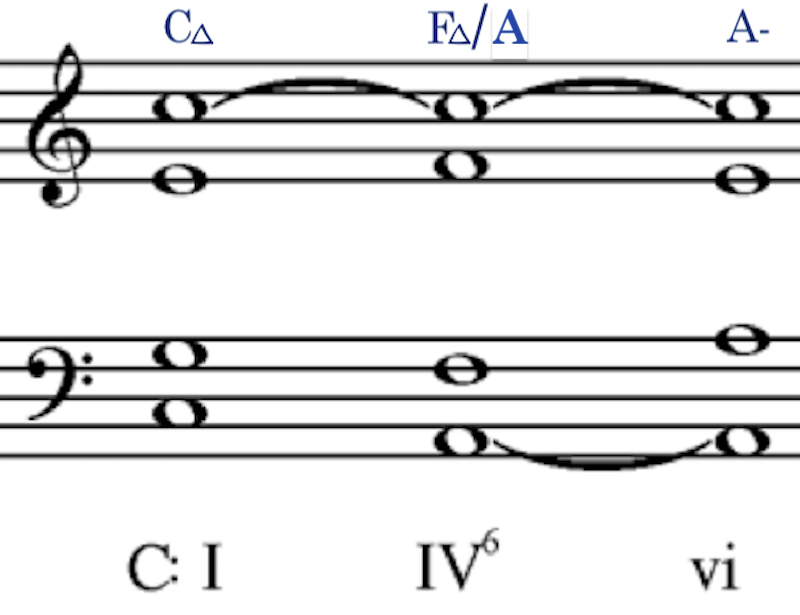

The primary tonal center (the key) of the musical phrase is shown at the beginning of the phrase below the bottom staff. We then label each chord according to its scale degree function using Roman numeral notation (abbreviated as R.N.). When we use R.N. labels, we will also indicate if the chord is in an inversion with a small superscript number just to the right of the Roman numeral, or if the chord contains tones beyond that of the triad (such as a seventh chord). This superscript number is called a figure, and taken collectively termed figured bass which is a notation originally invented for keyboard players to improvise musical accompaniments during the 17th and 18th centuries. This figured bass convention has carried onward to the present day as a way to identify chords and chord types in music theory analysis. As mentioned above, these labels always appear below the staff, centered below the bass-voice.

Furthermore, we will label the chords in each phrase using the more modern lead sheet chord notation above the top staff, centered above the soprano voice. As the name implies, this type of chord notation is often shown in jazz and popular music lead sheets (sometimes with guitar tablature as well), showing performers the intended harmony at any given moment in the composition upon which to play and improvise (jazz players will often term improvising over chords as “blowing over the changes”). Fortunately for us, both ways of labeling chords are easily accomplished in Noteflight when composing and realizing your own phrases.

Example 4. Example of chord labeling using both Roman numeral analysis and lead sheet notation.

More on Chord Labeling

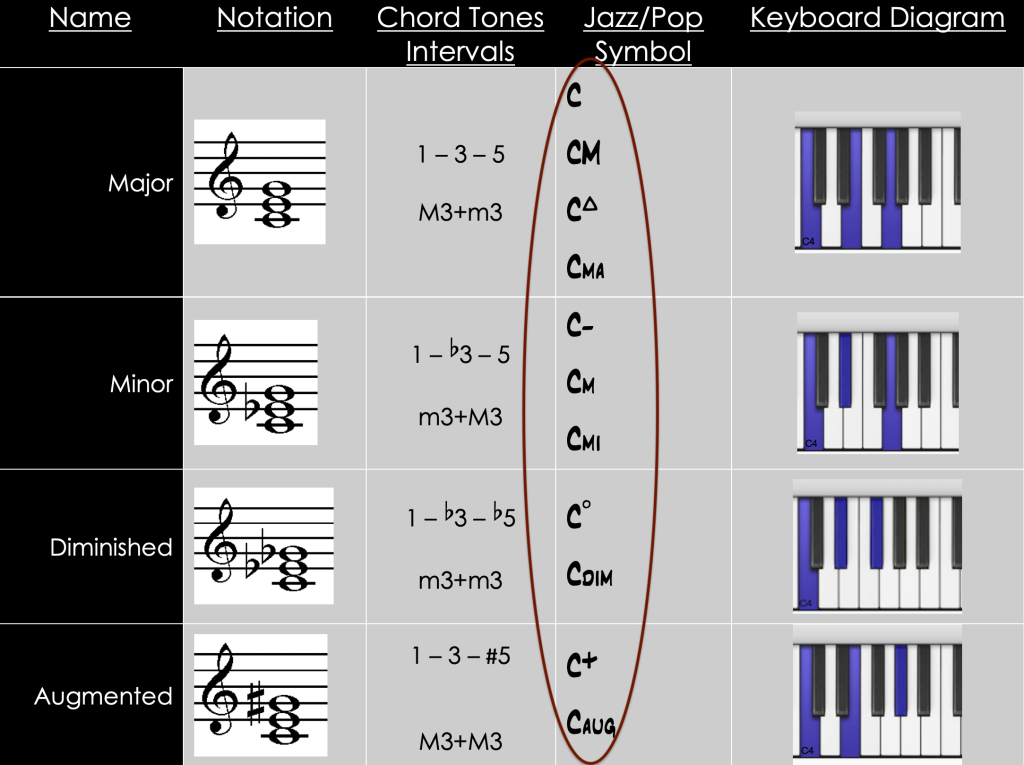

There are many different stylistic conventions to lead sheet chord labeling, often these are stylistic preferences established by publishers. For our purposes we will keep the labeling simple and follow these basic guidelines:

- Major triads: The pitch class of the root of the chord notated with an upper-case letter. I prefer also adding a small triangle symbol to the right of the letter but this is not necessary and is also not easily done when using Noteflight.

- Minor triads: The pitch class of the root of the chord notated with an upper-case letter as with the major triad, but follow this with a minus sign “-” immediately to the right of the letter. This will indicate a minor chord quality.

- Diminished triads: The pitch class of the root of the chord notated with an upper-case letter followed by a superscript “O” to the right of the letter. This will indicate a diminished chord quality.

- Augmented triads: The pitch class of the root of the chord notated with an upper-case letter followed by a superscript “+” to the right of the letter. This will indicate an augmented chord quality.

- Inversions: The root and chord quality as indicated above, but adding a slash “/” to the right followed by the pitch class of the note found in the bass (also in upper-case).

Figure 1 below shows the common triads with various chord notation conventions for easy reference.

Figure 1. The four common triads and, circled, the common lead-sheet naming conventions.

Seventh chords and their associated labels will be covered in a later chapter.

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

A vertical sonority.

A harmonic progression, also known as a chord progression, is the movement from one chord to another, often in such a way as to create or define the structural foundation of a work, song, or piece of music, particularly music in the Western tradition.

An independent, monophonic part within a piece of music (instrumental or vocal). Each voice may be played by a different instrument, or multiple voices may be played by one instrument (especially with polyphonic instruments such as they keyboard or guitar)

A traditional approach to music composition pedagogy focused on counterpoint as a way of learning to think of music horizontally (melodically) and vertically (harmonically) simultaneously. Consists of five “species,” each of which focuses on a single compositional element.

A four part musical texture with soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B) parts, abstracted through voice.

A musical texture that is sometimes interchanged with SATB style or a homophonic musical texture with melody and chordal accompaniment.

The highest part in SATB style, written in the treble clef staff with an up-stem; its generally accepted range is C₄–G₅.

The second-highest voice part in SATB style, written in the treble clef staff with a down-stem; its generally accepted range is G₃–D₅

The second lowest part in SATB style, written in the bass clef staff with up-stems; its generally accepted range is C₃–F₄.

The lowest voice in SATB style, written in the bass clef staff with a down-stem; its generally accepted range is E₂–C₄

The intervals between voices. For chords in strict SATB style, there should be no more than an octave between upper voices (soprano and alto, alto and tenor), and no more than a twelfth between the tenor and bass

Distribution of notes in a chord into idiomatic registers for performance.

Any combination of three or more pitch classes that sound simultaneously (at the same time).

A pitch that belongs to a chord. Example: a c major triad has three chord tones, pitch-classes C, E, and G.

A chord spacing in which the chord fits within one octave.

Notes of a chord are spaced out beyond their closest possible position

the art or technique of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction with another, according to fixed rules. Literal meaning is "point against point" which we interpret as "note against note"

The way a specific voice within a larger texture moves when the harmonies change. For example, in a choir with four parts, soprano/alto/tenor/bass, one might discuss the voice leading in the tenor part as the entire choir moves from I to V.

A relatively complete musical thought that exhibits trajectory toward a goal (often a cadence).

The duration of musical sounds and rests in time.

An indication of meter in Western music notation, often made up of two numbers stacked vertically.

A recurring pattern of accents that occur over time. Meters are indicated in music notation with a time signature.

A note value that lasts the duration of two half notes. Notation: 𝅝

Music sung in two or more distinct parts, with two or more singers assigned to each part. Choral music is necessarily polyphonal—i.e., consisting of two or more autonomous vocal lines. It has a long history in European church music (especially Lutheran) and in American Gospel tradition.

1. A scale, mode, or collection that follows the pattern of whole and half steps W–W–H–W–W–W–H, or any rotation of that pattern.

2. Belonging to the local key (as opposed to "chromatic").

A three-note chord whose pitch classes can be arranged as thirds.

A group of pitches that are octave equivalent and enharmonically equivalent.

The lowest note of a triad or seventh chord when the chord is stacked in thirds.

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a third (major or minor) above the root.

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a fifth (perfect, augmented, or diminished) above the root.

Two staves placed one above the other, connected by a brace. The top staff has a treble clef, while the bottom staff has a bass clef.

Ordering the notes of a chord so that it is entirely stacked in thirds. The root of the chord is on the bottom.

The density of and interaction between voices in a work

Duplicating some notes of a chord in multiple parts.

In tonality, the tonic (tonal center) is the tone of complete relaxation and stability, the target toward which other tones lead and to which all other tones in the mode/scale relate. The tonal center is defined as scale degree 1.

The relative position of a note within a diatonic scale. Indicated with a number, 1–7, that indicates this position relative to the tonic of that scale.

The role that a musical element plays in the creation of a larger musical unit.

A way of labeling chords according the the scale degree upon which the chord is built in tonal music. The scale degree number is represented as a Roman numeral as opposed to an Arabic numeral and the case of the Roman numeral is often used to denote the quality of the chord with Upper Case as major and Lower Case as minor.

When the bass note of a harmony is not the root of the chord. For example, when the third of the chord is in the bass instead of the root.

Refers to the 7th of a chord. For example, V7 in the key of C is spelled G-B-D-F. The note F is the chordal 7th. We say chordal 7th to distinguish it from the leading-tone (Ti, [latex]\hat{7}[/latex]).

Arabic numerals and symbols that indicate the intervals above a bass note to be realized into chords and non-chord tones by performers. Used also for identification of chords in Roman numeral harmonic analysis

A type of jazz/pop score that typically notates only the melody and the chord symbols (written above the staff).

Tablature (or tabulature, or tab for short) is a form of musical notation indicating instrument fingering rather than musical pitches. Tablature is common for fretted stringed instruments such as the guitar, lute, etc.

A triad whose third is major and fifth is perfect.

A triad whose third is minor and fifth is perfect.

A triad whose third is minor and fifth is diminished.

A triad whose third is major and fifth is augmented.

A triad with an additional third above the fifth, creating a seventh between that top note and the bass and totaling four notes.