Western Harmonic Practice II: Chromaticism and Extended Tonality

18 Chord Borrowing II: Chromatic Voice Leading and Other Borrowed Chords

Key Takeaways

This chapter explores the expansion from strict diatonic voice-leading to chromatic voice-leading, introducing additional borrowed chords available from the secondary key areas explored in the previous chapter. Chromatic voice-leading enriches harmonic possibilities and emotional depth in music.

- Chromatic Motion: Chromatic voice-leading involves ascending and descending motions most often filling in diatonic scale degrees.

- Use of Intervals: Emphasis is on smooth, melodic voice-leading. Augmented and diminished intervals are less strictly handled but awkward intervals are still to be avoided in favor of familiar diatonic voice-leading where possible.

- Chromaticism in the Minor Mode: Chromaticism allows for new voice-leading opportunities in the minor mode, beyond traditional pivot-tone guidelines, though their importance remains.

- Secondary Borrowed Chords: Borrowing additional chords from secondary key areas outside of the dominant introduces additional possibilities, often enriching modulations and providing additional harmonic variety. Borrowed chords should fulfill their secondary key area function and be used with moderation to maintain primary key stability.

- The Fully Diminished Seventh Chord: The fully diminished seventh chord is a rootless voicing of a Dominant ninth chord (with a lowered ninth located a minor third above the seventh). This chord is treated as a Dominant and may be used anywhere a dominant chord may appear (except for the final cadence of a musical phrase).

Chromatic Voice Leading

Until this point, we have voice-led all of our counterpoint and four-part SATB assignments using only diatonic voice-leading, even when introducing non-diatonic tones such as with secondary dominants. With the expanded richness of borrowed chords, other harmonies, and upcoming modulation schemes, we can now begin to incorporate chromatic voice-leading. Chromaticism not only facilitates new harmonic possibilities but also adds additional depth to dramatic and emotional expression in tonal music.

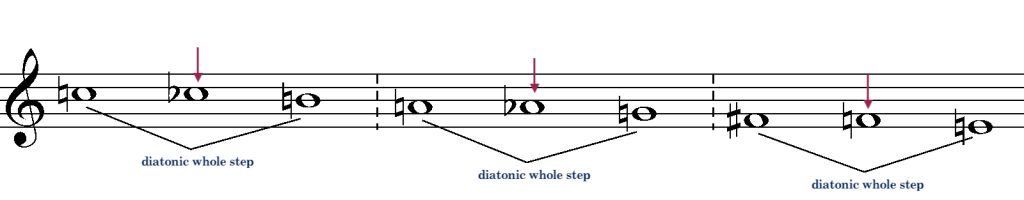

Chromatic voice-leading includes two types of motion: Ascending (upward) and Descending (downward). In both cases, chromatic steps serve to “fill in” the gap between a whole step formed by two diatonic scale degrees in the current key. It’s crucial that, whenever possible, voice-leading fulfills this function:

While augmented and diminished melodic intervals (beyond the tritone as an augmented fourth or diminished fifth) are now available, strive for smooth, melodic voice-leading. Avoid awkward intervals when possible and prefer diatonic voice-leading. See Schoenberg Example 136 below for chromaticism in practice.

Chromaticism and the Minor Mode

The introduction of chromaticism brings new voice-leading possibilities that can supersede pivot-tone guidelines. However, the significance of pivot tones should not be underestimated. Whenever possible, voice-lead these tones as previously outlined in Chapter 12: The Minor Mode – An Introduction.

Other Secondary Borrowed Chords

By extending the concept of borrowing chords, we explore the additional possibilities within secondary key areas. These chords, containing non-diatonic tones, enrich the harmonic landscape, especially when paired with chromatic voice-leading. Their function within the secondary key area’s context is crucial, particularly when a leading-tone appears. Often these chords can be effective in enhancing modulations and providing contrast in harmonic progressions.

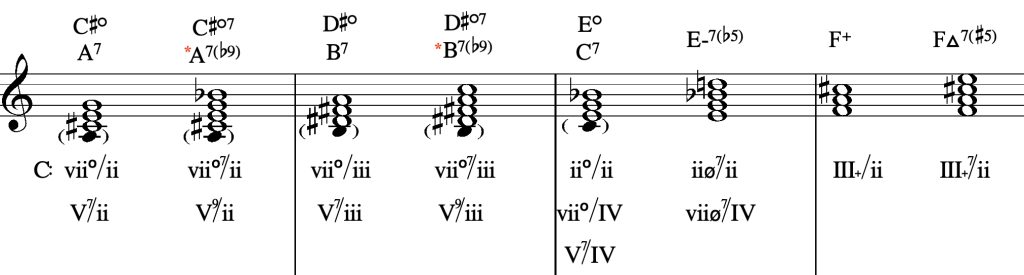

Secondary Chords in Major

In the major mode, we get a variety of chords from secondary key areas. In order for a chord to be considered a borrowed chord it must, by definition, introduce a non-diatonic tone to the prevailing primary key. Figure 3A and 3B illustrate such chords in C major:

Note: Chords marked with a red asterisk are dominant flatted ninth chords, voiced as fully diminished seventh chords. Their application and extended use of these important chords will be discussed in the next chapter.

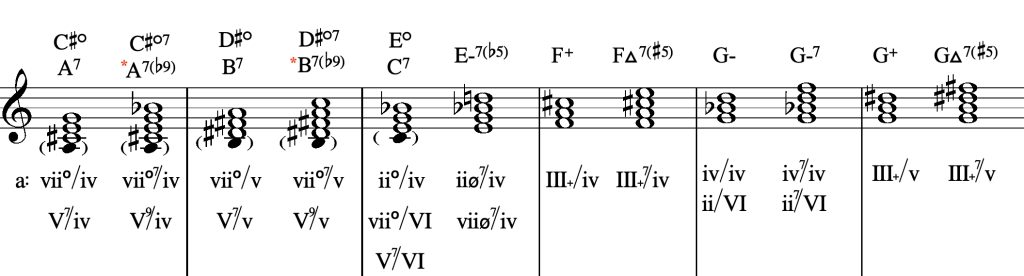

Secondary Chords in Minor

In the minor mode, the availability of chords mirrors that in major, with some chords omitted as they are already accessible via the raised (ascending) form of minor. Only chords that cannot be introduced in either the natural or raised forms of minor are considered borrowed from secondary key areas. Below is a comprehensive list for A minor:

When integrating these chords, consider their function within the borrowed key area and introduce non-diatonic tones thoughtfully, either diatonically or chromatically. Pivot-tone guidelines may be suspended when using borrowed chords and chormatic voice-leading.

The Fully Diminished Seventh Chord

We learned a while back that the diminished triad (leading-tone in Major / super-tonic in minor) is, in fact, an incomplete Dominant seventh chord.

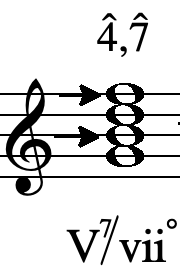

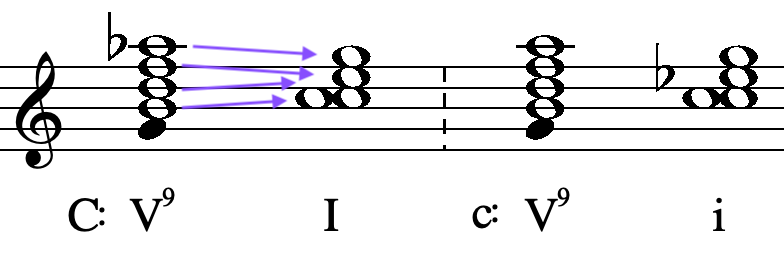

We may extend this concept of a rootless voicing now to the fully diminished seventh chord and, by way of extension, this chord now becomes a rootless voicing of a ninth chord; specifically this chord is a Dominant seventh chord with a ninth chord tone located a minor third above the seventh chord tone. In the minor mode, this chord occurs in harmonic minor, building a ninth chord on the Dominant. In the major mode we must lower the natural ninth by a half step, effectively borrowing the chord from the parallel minor mode via modal interchange (modal interchange is covered in depth later).

In a four part texture, this chord is most often voiced in the form of a fully-diminished seventh chord. While the root is not voiced, the chord itself has several very interesting properties which, when used well, can be very powerful and effective. First, the chord contains two interlocking tritones, both of which have resolving tendencies that will be discussed in more depth later.

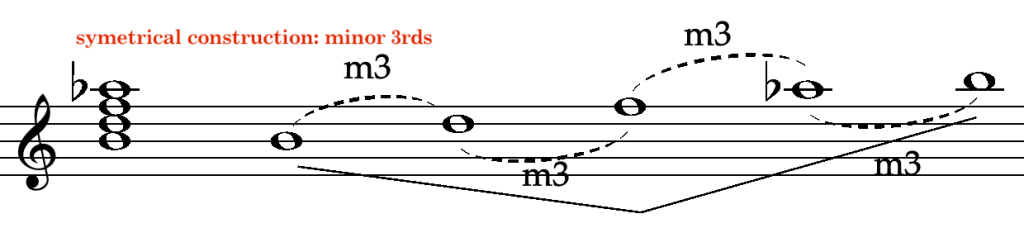

Second, the chord is a perfectly symmetrical four-part division of the octave. It is one of two perfectly symmetrical chords (the other being the augmented triad).

This chord resolves cleanly anywhere the Dominant seventh might resolve, with all tones moving smoothly by stepwise motion into chord tones on a resolution chord. While the example below shows the resolution to the Tonic, it just as easily resolves to the SubMediant and SubDominant in deceptive cadential situations.

In four part SATB textures, this chord does not require and special preparation so long as it is used in accordance with its function as a Dominant.

Borrowed Chords and Chromaticism: Guidelines

- Borrowed chords may replace diatonic chords if they serve the harmonic function within the secondary key area. It is the composer’s discretion with regard to their use, being mindful of not overusing them to undermine the primary key’s stability.

- Borrowed chords, especially secondary Dominants, are effective for providing interest and variation in reharmonizing existing pieces/songs.

- The root motion relationships remain consistent, even when altering diatonic scale degrees in relation to the primary key.

- Chromatic voice-leading enriches melodic movement, ideally fulfilling rising or falling chromatic motion between diatonic scale degrees.

- In the minor mode, while pivot tones are essential, the introduction of borrowed chords and chromatic voice-leading can offer alternative voice-leading paths, guided by the logic and intention of the harmonic progression.

- The fully-diminished seventh chord may be used freely as a Dominant with the exception of an Authentic cadence at the close of a piece/song. It is thought of as a rootless voicing of a Dominant seventh with a lowered ninth chord tone and is voice-led accordingly. No preparation is required for any of the tones in the fully-diminished seventh chord.

Schoenberg Theory of Harmony Examples

RWU EXERCISES

Using Secondary Chords and Chromaticism

Using the template below, please do the following:

1. Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, two in MAJOR and two in MINOR of at least 10 to 16 chords in length:

-

- Modulate to an adjacent key area (+1 or -1) using the common chord modulation schema.

- Use at least one (1) secondary dominant and two (2) secondary other borrowed chords in each phrase

- Use at least one (1) fully-diminished seventh chord as a Dominant.

- Try different approaches, some as triads, some as sevenths.

- Consider, when constructing your phrases, the root motion and overall function of the chord progression

Exercise 270 #4: (PW-4): Borrowed Chords and Chromaticism

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

2. Reharmonization of Amazing Grace

Make four (4) versions using different substitutions based on what we’ve learned in both chapters on borrowing.

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

A five note chord constructed in thirds above a root tone. It can be thought of as an extension of a seventh chord with an additional chord tone located a third above the seventh.

The intermixing of major and minor versions of 3̂, 6̂, and/or 7̂ within a composition.