Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

15 Harmonic Direction II: Tonality and Cadences

Key Takeaways

This chapter elucidates the process of identifying the key and tonal center in tonal music. We explore the importance of establishing a tonal center through specific musical elements, particularly focusing on the intersectional roles of the Circle of Fifths and scale degrees in distinguishing the tonal center and the use of the cadence in firmly establishing the tonality.

- Identifying the Key: Discerning the key of a music piece requires more than just the tonic triad or a repeated chord. It’s essential to understand the underlying musical markers via the defining scale degrees as overlapping, common chords in closely related keys can create ambiguity.

- Establishing the Tonal Center: The defining scale degrees in major are

and

and  . In minor, the key and mode is defined by scale degrees

. In minor, the key and mode is defined by scale degrees  ,

,  , and

, and  .

. - Tritone Resolutions: Diatonic tritones in both major and minor modes exhibit specific melodic voice-leading tendencies.

- Role of Cadences: Cadences play a pivotal role in establishing the tonal center and the key by emphasizing the key and mode defining scale degrees, omitting neighboring keys from consideration.

- The Four Cadence Types: Authentic (Perfect: PAC / Imperfect: IAC), Deceptive (DC), Half (HC), and Plagal (P

- Guidelines for Better Progressions: Culminating general guidelines are provided in summary to help craft better progressions, emphasizing root progressions, chord usage, and voice leading.

Understanding Keys

How do we identify the key of a tonal music piece? Simply sounding the tonic triad or starting and concluding a musical phrase with an identical chord doesn’t unequivocally confirm the key. To truly discern the key and establish a robust tonal center, our mind requires specific musical cues to form a contextual understanding. What are these auditory markers?

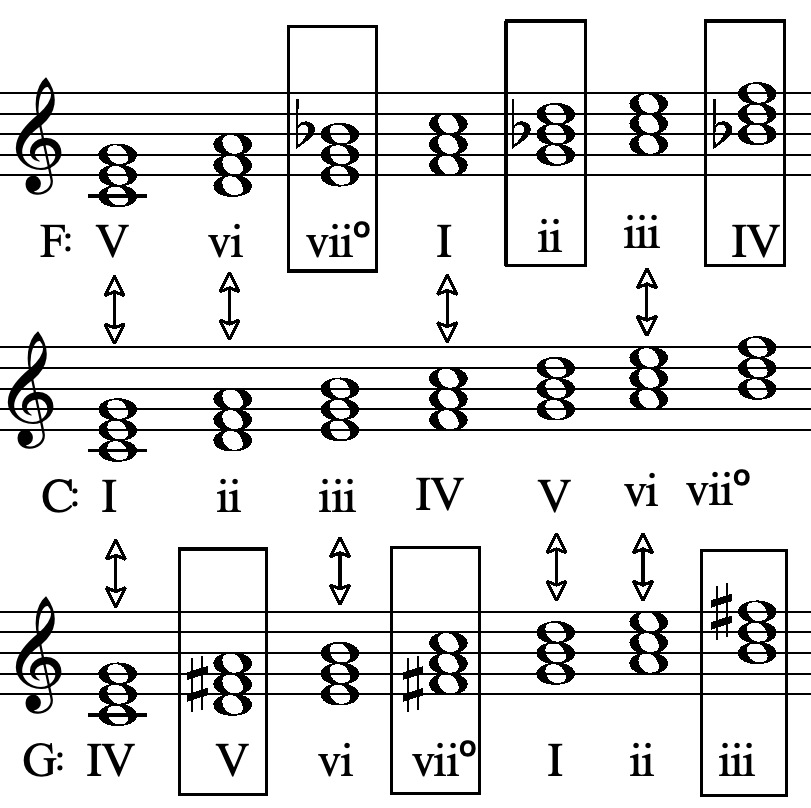

Consider the keys that are closely related, positioned adjacent to one another on the Circle of Fifths:

It’s evident that many chords overlap among these keys. If our aim is to denote C major and we play chords common to G major, ambiguity arises between C and G major. Likewise, playing chords shared between C and F major introduces uncertainty about the key.

Establishing the Tonal Center

To differentiate and firmly set the key, one should play notes exclusive to the desired key, excluding the ones from adjacent keys on the Circle of Fifths. Investigation reveals that in the major mode, scale degrees ![]() and

and ![]() are pivotal for key determination. In minor mode,

are pivotal for key determination. In minor mode, ![]() remains crucial, while the leadng-tone

remains crucial, while the leadng-tone ![]() is derived from the Ascending form. The uniqueness of the minor mode is further reinforced by scale degrees

is derived from the Ascending form. The uniqueness of the minor mode is further reinforced by scale degrees ![]() and

and ![]() . Together, These degree pairs inherently demarcate the diatonic tritone, lending each mode its distinctive sound and attributes.

. Together, These degree pairs inherently demarcate the diatonic tritone, lending each mode its distinctive sound and attributes.

Cadences are essential here for helping us establish the tonal center and the key, as they not only conclude a harmonic sequence but also distinctly affirm the key by emphasizing the above-discussed defining scale degrees, thereby omitting neighboring keys from the tonal consideration.

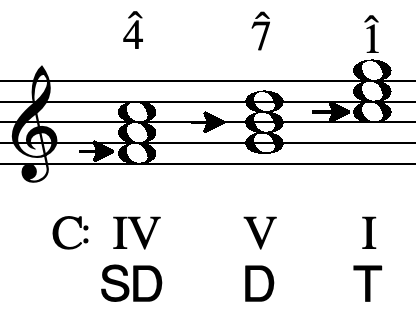

Major Mode

In the major mode, the SubDominant and SuperTonic chords, sourced from the SubDominant region, encompass the defining scale degree ![]() . Meanwhile, chords from the Dominant region embed the leading-tone, scale degree

. Meanwhile, chords from the Dominant region embed the leading-tone, scale degree ![]() .

.

Both the Major-Minor (Dominant) Seventh chord and the Leading-Tone diminished triad encompass scale degrees ![]() and

and ![]() . These chords, by possessing both of the defining scale degrees, robustly fortify the tonal center in major mode.

. These chords, by possessing both of the defining scale degrees, robustly fortify the tonal center in major mode.

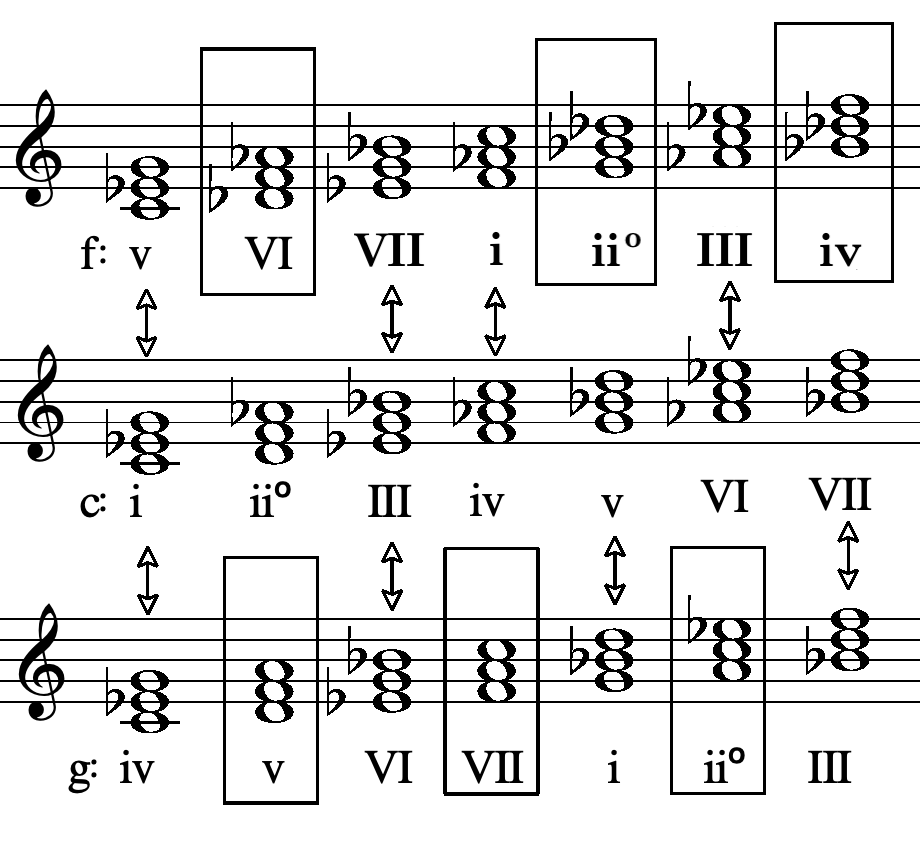

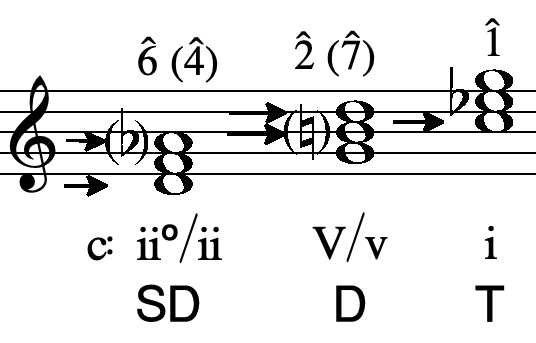

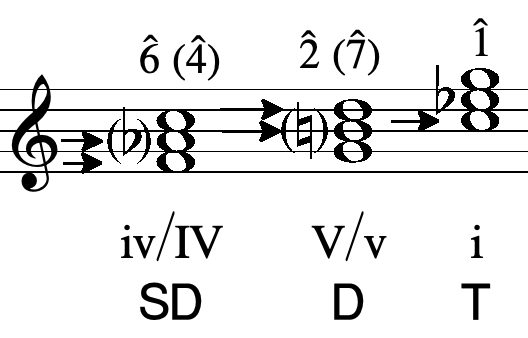

Minor Mode

The mechanism in the minor mode parallels the major but offers more variety due to the dual nature of modern minor (i.e. the Ascending and Descending forms). Both the SubDominant and SuperTonic encompass key and mode-defining scale degrees ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . It’s noteworthy that either minor form, with a variable scale degree

. It’s noteworthy that either minor form, with a variable scale degree ![]() serve equally well in defining the key. In addition, when in the Ascending form, we get a leading-tone scale degree

serve equally well in defining the key. In addition, when in the Ascending form, we get a leading-tone scale degree ![]() , also providing a strong sense of definition.

, also providing a strong sense of definition.

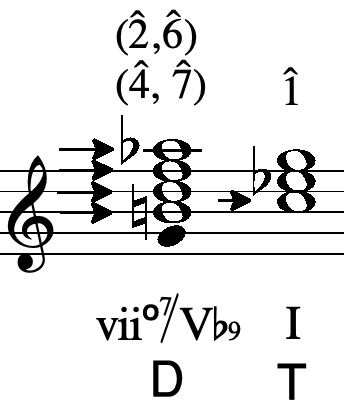

The fully diminished seventh chord, built on the raised scale degree ![]() from the Ascending (Harmonic) form of minor, and possessing the Natural sixth scale degree, is very potent, encapsulating all minor key and minor mode-defining scale degrees. This chord, akin to the diminished triad, can be thought of as an incomplete, rootless voicing of a ninth chord founded on the Dominant, essentially as a Dominant Seventh with an added flat ninth.

from the Ascending (Harmonic) form of minor, and possessing the Natural sixth scale degree, is very potent, encapsulating all minor key and minor mode-defining scale degrees. This chord, akin to the diminished triad, can be thought of as an incomplete, rootless voicing of a ninth chord founded on the Dominant, essentially as a Dominant Seventh with an added flat ninth.

We will come back to the fully diminished seventh chord and explore its many additional possibilities in a later chapter.

Tritone and Scale Degree Melodic Tendencies

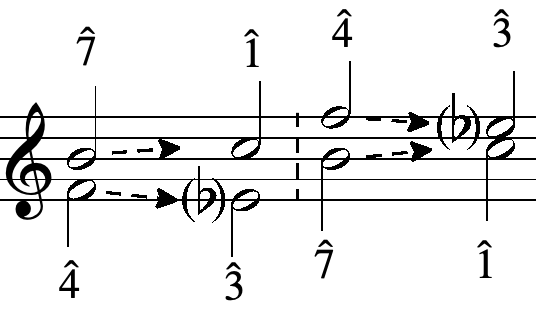

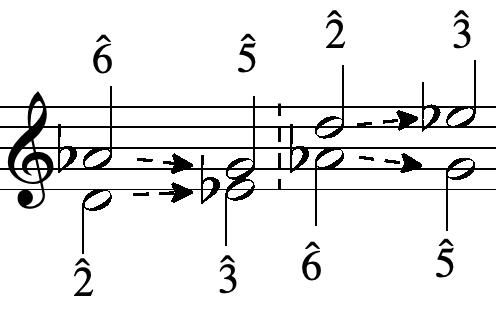

Earlier, we delved into the tendencies of the pivot tones in minor mode (tendency tones). Expanding on this concept, the diatonic tritones in both major and minor modes, demarcated by key and mode-defining degrees mentioned above, exhibit specific melodic voice-leading propensities. In both major and minor:

In Natural (Descending) minor:

The Four Cadence Types

There are four primary types of cadences (closes) in tonal music: Authentic, Deceptive, Half, and Plagal.

Authentic

The Authentic cadence is the most definitive cadence, affirming the key and concluding on the Tonic triad. There are two types: Perfect (top voice melody terminates on the Tonic) or Imperfect (top voice melody concludes on another scale degree).

When labeling the cadence in a piece of music, we use the following abbreviations: PAC = Perfect Authentic Cadence. IAC – Imperfect Authentic Cadence.

In SATB voice leading, the most conclusive version of an Authentic cadence will have the following:

- The Dominant and Tonic in root position.

- The Dominant chord must be a complete chord with the root sounding (i.e. not a diminished triad or fully diminished seventh).

- The leading tone scale degree in the Dominant should always lead to the Tonic in the same voice.

- Seventh chords, except for the Tonic triad, may be used, provided the voice-leading allows.

Tripled Root for final Tonic: It is sometimes necessary, especially when voice-leading the Dominant seventh to the Tonic in a Perfect Authentic Cadence, to voice-lead into a final Tonic triad with a tripled root. Thus we will have 3 roots and the third in the SATB texture. It is permissible to do this, but only for the very final chord of the phrase.

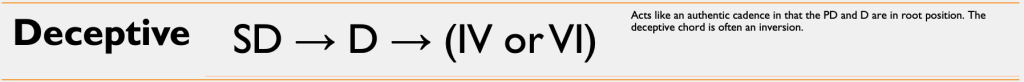

Deceptive

The Deceptive cadence seemingly sets up a closure but veers away from the Tonic chord, adding a twist to the listener’s expectation. It is often a good way to both reaffirm a tonal center and key, but also provide further momentum in the musical phrase.

We label the Deceptive cadence in a piece of music with the abbreviation DC.

Half

The Half cadence offers a moment of pause, culminating on the Dominant chord rather than the Tonic, which then often moves on with a new musical phrase.

We label the Half cadence in a piece of music with the abbreviation HC.

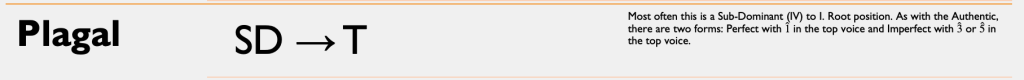

Plagal

Finally, we have the Plagal cadence, often termed the “Church” or “Amen” cadence. This cadence omits the Dominant, resulting in a less decisive closure. It is often used as an extension to an ending, after the sounding of an Authentic cadence, the purpose being to provide a more resolute conclusion. This cadence type appears regularly in popular song and contemporary pop, country and folk music.

We label the Plagal cadence in a piece of music with the abbreviation PlC.

As with the Authentic cadence, we have two forms of Plagal: Perfect and Imperfect, defined the same way as in the Authentic cadence by way of which scale degree is in the top melodic voice.

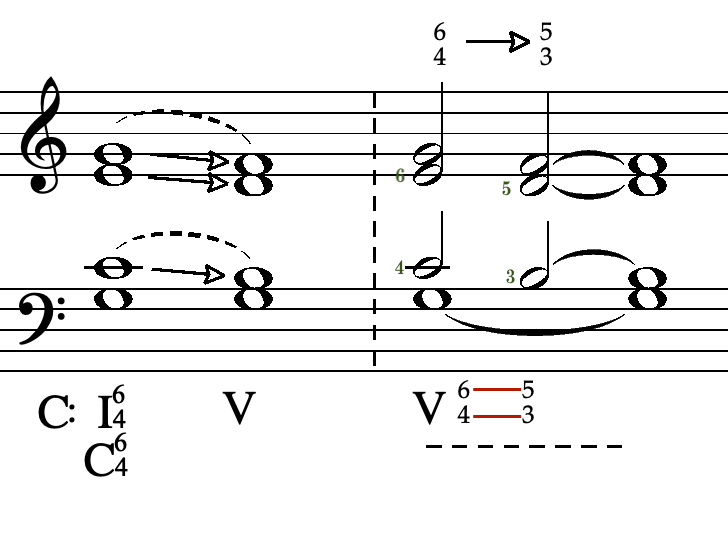

The Second Inversion (Six-Four) Triad in the Cadence

The Tonic second inversion triad, or the “Six-Four” chord, is pivotal in cadences. In the cadence. this chord is heard as a Dominant 6-4 dissonant suspension rather than a Tonic chord. How is this possible? The Dominant tone (scale degree [latex](\hat5)[/latex) is in the bass and, as we already know, any bass voice will exerts it’s overtone series over the sounding notes above. Thus, the chord, by its very nature, is unstable, and it is quite easy and natural for the upper tones to have a strong pull toward neighboring tones that resolve in a root position chord (with the bass tone as the root), in essence, coming into “focus” and resonance with the harmonic series. This is one reason why we must be careful when using the second inversion triad, its inherent instability and its being at odds with the sounding tones.

We may use this Cadential 6/4 chord in any Authentic cadence, sounding immediately after any pre-Dominant (SubDominant) chord, before the sounding of the Dominant chord. The effect is powerful and creates, as mentioned above, a sense of prolonging and tension, further elevating the final resolution to the Tonic. While it might be used as part of a Deceptive cadence, due to its power and affect, it is not well suited to such a situation unless very strongly warranted by the musical context.

Guidelines for Better Progressions

Root Progressions (in Major and Minor)

- Ascending root progressions, which move a fourth upward or a third downward, can occur anytime. However, avoid repetitive usage.

- Descending progressions, moving a fourth downward or a third upward, should be used when they contribute to an overall upward motion.

- Adjacent progressions sparingly unless specified otherwise. They aren’t prohibited.

Chord Usage (in Major and Minor)

Triads

- Triads in root position are versatile and may be used anytime.

- Sixth chords enrich voice leading, especially in outer voices, and prepare dissonances. They may be used anytime (except at the start or end of a musical phrase).

- Use six-four chords cautiously. They’re optimal in cadences (i.e. the Cadential 6/4) and with a moving bass-line in stepwise motion. Exercise care in all other situations.

- Diminished triads give a sense of necessity when introducing a chord, and further may be considered as a Dominant seventh chord.

Seventh Chords

- Seventh chords are as versatile as triads when prepared and resolved. They’re best used where the seventh demands a specific resolution or treatment.

- Inversions of seventh chords improve voice leading.

The Minor Mode

- The careful handling of the pivot/tendency tones are essential. Incorporate the pivot tones during root progression harmonic progression outlines.

- Staying exclusively in one region (Ascending or Descending) can jeopardize the minor mode’s character.

- Transitioning between regions should respect pivot tones (i.e. the four pivot tone guidelines).

- Triads may require inversions to prepare or resolve dissonances, especially with a pivot tone in bass.

- The same rules apply to seventh chords.

- After certain diminished triads, it’s generally better to use the Ascending major Dominant chord (V).

- All diminished triads and their seventh chords have a distinct drive due to their dissonance.

- The augmented triad’s versatility lets it transition between ascending and descending minor scales.

Voice Leading

- Avoid unmelodic intervals, especially without altered chords.

- Avoid repetitive tone progressions with the same harmony.

- Aim for a high and possibly a low point.

- Use steps and leaps for varied interval sequences, maintaining a mid-range.

- After a significant leap from the mid-range, try to return to it.

- If the mid-range is left stepwise, perhaps balance with an octave leap.

- If repetition is unavoidable, a direction change might help.

- In Cadences, the leading tone scale degree in the Dominant should lead, in the same voice, to the Tonic.

- Never double a dissonance.

- Double the Root of any Triad where possible, but other doubling is possible:

- First inversion better to have the fifth doubled, then the third

- Second Inversion, better to have the third doubled.

- Do not omit any chord tones if possible. If needed, you may omit the fifth of any stable major or minor triad or seventh chord.

- You may triple the root in the final Tonic triad on the close of a phrase in an Authentic cadence.

- The melodic guidelines apply primarily to soprano and bass. If applied to middle voices, it elevates the overall smoothness. However, focusing on the outer voices is sufficient for now.

EXAMPLES: Triad Inversions and Seventh Chords in the Minor Mode

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

RWU EXERCISES

Major and Minor: Chord Connection with Non-Common Chord Tones and Freer Treatment of Dissonance

Using the template below, please do the following:

- Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, at least 7 to 12 chords in length:

- At least two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice) and two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

- Consider the general guidelines above when constructing your phrases

- Each phrase should be planned out with root progression and harmonic regions in mind.

- Each phrase should have a good mixture of seventh chords and triads.

- Each phrase should contain one Deceptive cadence somewhere within the phrase and end with an Authentic cadence (perfect or imperfect)

- Two of your phrases should end with an Authentic cadence which uses the Cadential Six-Four chord. Label this chord as C6/4

- Label your cadences with the following text: DC (Deceptive Cadence), IAC (Imperfect Authentic Cadence), PAC (Perfect Authentic Cadence).

- At least two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice) and two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Schoenberg Theory of Harmony Examples

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

a musical interval with a distance of three (3) whole steps, hence the name "tri" (3) and "tone" (whole step). Often this interval is spelled as a diminished fifth or an augmented fourth.

A melodic and harmonic goal. In classical tonal music, cadence types include Perfect Authentic (PAC), Imperfect Authentic (IAC), and Half (HC).