Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

7 Voice-Leading I: Common-Tone Chords in the Major Mode

Key Points

Here we engage in the application of concepts introduced regarding chord progressions and voice leading in four part SATB chorale style in the Major mode. In our first, root position musical phrases we highlight the importance of:

- Voice leading to produce a smoothness of melodic line, avoiding unnecessary leaps and skips, and avoiding dissonant melodic intervals (augmented, diminished, etc.)

- Voice leading to avoid the overpowering force of perfect parallel motion between them (i.e. parallel fifths, etc.)

- Connecting chords one to another which have at least one tone in common.

- Being mindful of the vertical spacing of the voices so they do not stray too far apart or come too close so as to cross one another

In this chapter we will learn how to connect chords together into harmonic progressions, forming short phrases in a chosen diatonic major key. Our phrases, for now, will be very short and we will not concern ourselves with the overall shape of the chord progression, but rather with best practices in terms of voice leading each of the SATB voices from one chord to the next. Our first exercises will also not be concerned with meter and, as such, will not have time signatures. The only note values we will use will be whole notes.

Voice Leading

As introduced in the previous chapter, In four part SATB chorale style, we still consider each voice as a separate melodic line. Many of the things we learned about writing a good melody in our study of counterpoint continue to apply. When working with voices in this way, we are engaging in a process called voice leading. Our SATB chorale style melodic lines will be constructed with the following basic guidelines in consideration:

- All four voices will be diatonic and always stay within the mode (key). For now, we will not use any accidentals or modifications of the parent key. Chromaticism is not allowed at this time.

- Generally speaking, melodies should have a focal point, either high or low (a ”zenith” or “nadir”) if at all possible within the span of the musical phrase.

- Melodies should strive for smoothness and thus any melodic motion should be mostly stepwise, using skips and leaps sparingly. When skips and leaps are used, they should, whenever possible, be “smoothed out” by movement in the opposite direction, preferably by stepwise motion.

- Leaps of larger than a sixth, with the exception of the octave should not be used.

- Steps, skips, or leaps which are augmented or diminished should not be used.

- Avoid successive melodic skips, steps, or leaps that outline a dissonant melodic interval. In this case, as with counterpoint, dissonant melodic intervals are:

- An augmented or diminished interval of any size

- A seventh of any quality

- Any interval that exceeds an octave.

- In our first four part exercises, it is often the case that we have many repeated notes (or tied notes) in the voices. This is perfectly acceptable at first.

Chord Connection and Phrase Construction

A tonal harmonic progression may be evaluated in two ways. First we can look at the entire sequence of chords, taken as a whole, zoomed out to what we often refer to as phrase level in music. In our first exercises we will be less concerned with this level of evaluation but, later, as we learn more, we will be more and more conscious of how the chords all fit together supporting the musical shape of an entire idea, song, or piece of music. For now we will concern ourselves with the second way: locally, chord to chord.

When considering which chords may best go together from one to the next, we will use a few simple guidelines:

- For now, we shall connect chords together that share at least one common tone between them. The table below shows which chords, organized by scale degrees in Roman numeral notation, share common tones with one another. When choosing chords, you should identify which chord tones are common between them before connecting.

- As with our species counterpoint, parallel voice motion between any two voices that are of a perfect consonant interval (P5, P8, P1, or any compound interval of a perfect consonance), are to be strictly avoided. The reason is not that they sound necessarily bad, but because we are, as we did with counterpoint exercises, striving for as much independence between the voices as is possible. Perfect consonances that move in parallel with one another are far too close in the harmonic series as to promote a good sense of independent linear drive. [no, J.S. Bach will not kill a kitten when this happens… at least we don’t think he will]

- The voice space guidelines (interval distance between each of the voices respectively) as outlined in the previous chapter should be strictly adhered to.

- As with species counterpoint, voice crossing is not allowed at this time

- The melodic guidelines cited above are to be followed with care and attention.

- As a general rule: strive for the least possible motion melodically unless by doing so a problem is created (such as voice movement in parallel perfect intervals, etc.). Another way to think of it is take the path of least effort and resistance. This may not create the most interesting melodic shapes, but for now we are more concerned with proper connection and smoothness than that of melodic interest.

Chord Connection

The process of moving from one chord to another is a fairly straightforward process in four part SATB chorale style and may be summarized as follows:

- Find the common tones between the two chords with which you wish to connect. Remember: If the chords do not have tones in common you can not connect them (yet).

- Hold over all the tones which are common between the two chords with a tie.

- Move the other voices in to the nearest chord tone of the next chord, keeping in mind all of the guidelines regarding chord voicing, spacing, and voice leading (i.e. avoiding perfect parallel motion between voices, etc.). Remember, in almost all cases we will move to the nearest chord tone. A good way to think of this is as a path of least resistance. In other words: take the elevator, not the stairs!

- At the moment we will only use chords in root position. Thus the bass voice will always contain the root of the chord.

- We will only double the root for the time being. This means that every chord we voice in the four part SATB texture will contain two instances of the root with, as mentioned above, the bass voice taking one of those instances, followed by one instance of the third and fifth of the chord.

Special Consideration for Bass Voice Motion

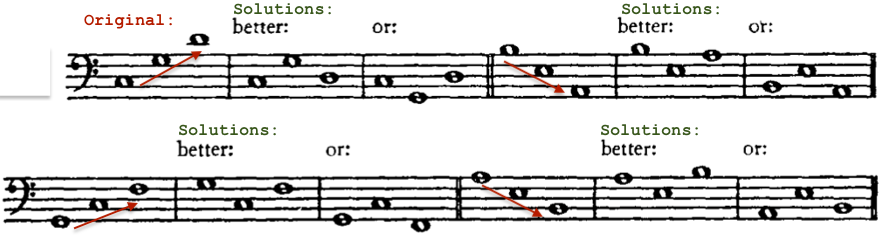

Since we are only working with root position voicings of our chords, the bass voice in our SATB chorale texture will necessarily always contain the root of the chord. Because we are only connecting chords that have at least one common tone in relation to one another, and adjacent chords are not permitted as a result, this will create a situation where the bass voice never moves in stepwise motion, but rather always by a motion of a skip or leap. Because of this, always try to move the bass voice in an opposite direction from the previous move and, when that is not possible (perhaps because of range, voice crossing, or other problem), avoid more than two successive skips/leaps in the same direction. This is generally good melodic practice regardless and, too, often a combination of skips or steps in one direction will create a compound melodic interval which will be dissonant. A few examples and solutions are provided for context below.

Example 1. Better solutions to bass voice melodic motion in root position only voicings

Constructing a Phrase

Now that we have established the basic principles and guidelines on how to handle the voices in a four part SATB chorale texture, and how to connect one chord to another, we will finally consider how to construct a short musical phrase. Once we have chosen a key (major mode for now), we can begin.

- Start with the Tonic (I) chord.

- Choose a path of succeeding chords, all by common tone relationships, using the table provided below as a steering guide.

- End with the Tonic (I) chord, aiming for a musical phrase of chords approximately four (4) to seven (7) chords in length.

Common Tone Chord Chart (Major Mode)

| Chord | Has common tones with... | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | iii | IV | V | vi |

| ii | IV | V | vi | (vii) |

| iii | I | V | vi | (vii) |

| IV | I | ii | vi | (vii) |

| V | I | ii | iii | (vii) |

| vi | I | ii | iii | IV |

| (vii) | ii | iii | IV | V |

Note: As you can see in the chart above, scale degree ![]() , vii, is both highlighted and parenthesized. For now we will avoid the use of the diminished triad: the triad which is naturally found on scale degree

, vii, is both highlighted and parenthesized. For now we will avoid the use of the diminished triad: the triad which is naturally found on scale degree ![]() in the major mode. This chord is considered unstable and contains a dissonance of a diminished fifth , and thus must be handled in a special way which will be shown in a later chapter.

in the major mode. This chord is considered unstable and contains a dissonance of a diminished fifth , and thus must be handled in a special way which will be shown in a later chapter.

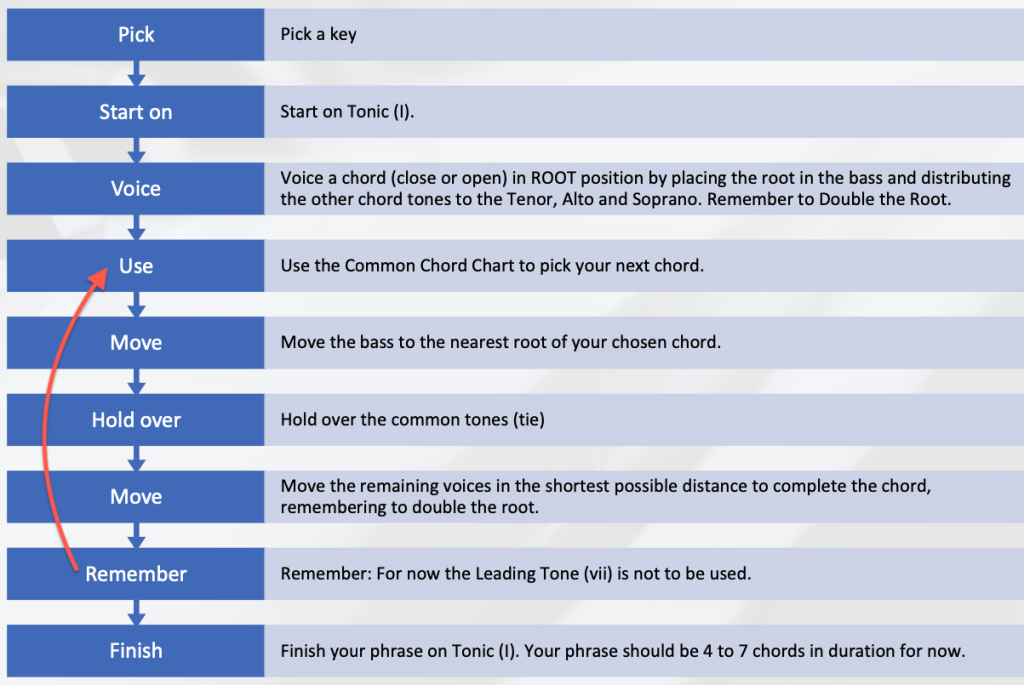

The chart below shows the entire process for composing a short tonal harmonic progression, using all of the guidelines and topics we have learned thus far:

EXAMPLES

Root Position Phrases in C Major, G Major, and F Major

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

RWU EXERCISES

Root Position Four Part SATB Chorale Style

Practice your voicing skills, using both close and open positions in the following two exercises:

Using the template below, do the following:

- Realize the given harmonic progression (the Roman numeral analysis and bass line is provided)

- Compose three more harmonic progressions of your choice, four to six chords in length, two in C Major, and one in any major key of your choosing.

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

Any combination of three or more pitch classes that sound simultaneously (at the same time).

A harmonic progression, also known as a chord progression, is the movement from one chord to another, often in such a way as to create or define the structural foundation of a work, song, or piece of music, particularly music in the Western tradition.

A relatively complete musical thought that exhibits trajectory toward a goal (often a cadence).

1. A scale, mode, or collection that follows the pattern of whole and half steps W–W–H–W–W–W–H, or any rotation of that pattern.

2. Belonging to the local key (as opposed to "chromatic").

A diatonic mode that follows the pattern W–W–H–W–W–W–H. This is equivalent to a major scale.

The way a specific voice within a larger texture moves when the harmonies change. For example, in a choir with four parts, soprano/alto/tenor/bass, one might discuss the voice leading in the tenor part as the entire choir moves from I to V.

A four part musical texture with soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B) parts, abstracted through voice.

An independent, monophonic part within a piece of music (instrumental or vocal). Each voice may be played by a different instrument, or multiple voices may be played by one instrument (especially with polyphonic instruments such as they keyboard or guitar)

A recurring pattern of accents that occur over time. Meters are indicated in music notation with a time signature.

An indication of meter in Western music notation, often made up of two numbers stacked vertically.

A note value that lasts the duration of two half notes. Notation: 𝅝

A seven note scale that follows the pattern of whole and half steps W–W–H–W–W–W–H. Since there are seven, there are in effect, seven different "modes" -- places we can start and thus rotate the pattern of whole and half steps.

Diatonic further refers to any music that is only made of the seven pitches derived from the local mode/key (as opposed to "chromatic" notes which fall outside any of those seven notes).

A term used to describe a piece's overall tonic. If a movement is in the key of A major, then the home key is A major. The term is used to distinguish itself from local keys.

Relating in some sense to the chromatic scale. The term may be used to refer to notes that are outside the given key.

A tone that is present in more than one chord.

The relative position of a note within a diatonic mode (scale). Scale degrees are indicated with a number, 1–7, that shows this position relative to the tonic (tonal/modal center) of that mode.

A way of labeling chords according the the scale degree upon which the chord is built in tonal music. The scale degree number is represented as a Roman numeral as opposed to an Arabic numeral and the case of the Roman numeral is often used to denote the quality of the chord with Upper Case as major and Lower Case as minor.

A pitch that belongs to a chord. Example: a c major triad has three chord tones, pitch-classes C, E, and G.

A traditional approach to music composition pedagogy focused on counterpoint as a way of learning to think of music horizontally (melodically) and vertically (harmonically) simultaneously. Consists of five “species,” each of which focuses on a single compositional element.

A type of voice motion when two voices move in the same direction in relation to each other and move by the same melodic interval and, thus, retain the same harmonic interval—for example, both voices move upward by a melodic second.

Perfect octaves (twelve semitones), perfect unisons (zero semitones), and perfect fifths (seven semitones). Perfect fourths (five semitones) are sometimes considered a perfect consonance, sometimes a dissonance; this depends on the context.

The distance between two notes.

Perfect Fifth

Perfect Octave

Perfect Unison

An interval that is larger than an octave.

A series of notes whose frequencies are multiples of the first frequency: 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5, etc. Starting with the pitch C₂, this would result in the series of pitches C₂, C₃, G₃, C₄, E₄, G₄, B♭₄, C₅, etc.

When a higher voice part moves below a lower voice part. In strict SATB style, the ranges of voices should not cross; the soprano must always be higher than the alto, the alto must always be higher than the tenor, and the tenor must be higher than the bass.

Connects two or more notes of the same pitch; notes after the initial one are not rearticulated.

Ordering the notes of a chord so that it is entirely stacked in thirds. The root of the chord is on the bottom.

The lowest note of a triad or seventh chord when the chord is stacked in thirds.

Duplicating some notes of a chord in multiple parts.

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a third (major or minor) above the root.

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a fifth (perfect, augmented, or diminished) above the root.

Distribution of notes in a chord into idiomatic registers for performance.

The lowest voice in SATB style, written in the bass clef staff with a down-stem; its generally accepted range is E₂–C₄

The density of and interaction between voices in a work

melodic motion to the next adjacent note (pitch) in the mode/scale (scale degree), either up or down.

Melodic movement by third.

A melodic interval o greater than a third.

An interval measured between two tones which have at least one tone in between (often two or more).

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord, relative to the surrounding musical texture.

The home note or home chord of a scale, or something with the function of that home note.

A triad whose third is minor and fifth is diminished.

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord.

An interval that is spelled as a fifth with a distance of six (6) half steps, one half-step shy of a perfect fifth. We also call this distance a tritone (three whole steps).

A chord spacing in which the chord fits within one octave.

Notes of a chord are spaced out beyond their closest possible position