Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

13 Voice Leading II: Chords with No Common Tones and Freer Treatment of Dissonance

Key Takeaways

This chapter delves deeper into the complexities of voice leading in tonal music, concerning chord connections with no common tones and the additional considerations and freer treatment of dissonance, notably the diminished fifth and the seventh in the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord.

-

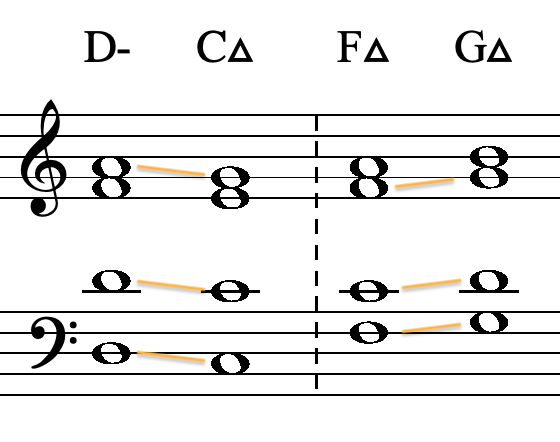

- Handling Root Adjacent Chords: Chords with no common triadic chord tones present challenges, particularly to avoid parallel octaves and fifths. Flexibility in voice-leading is necessary, with the overarching goal being smooth transitions that avoid pitfalls.

- Benefits of the Inversion: Using inversions, especially the first inversion triad, can aid in avoiding voice-leading problems like parallel intervals, offering both smoother and more interesting harmonic progressions.

- Freer Treatment of the Diminished Fifth: The diminished fifth dissonance in the diminished triad and seventh chords containing a diminished fifth can be introduced without strict preparation and can be resolved more freely.

- Relationship Between Diminished Triad and Dominant Seventh: The diminished triad can be viewed as an incomplete voicing of the dominant seventh chord. These chords are functionally equivalent due to their shared tritone, allowing them to be substituted for one another.

- Freer Treatment of the Dominant Seventh: The dissonance in the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord can also be treated more freely, in a similar way as to the diminished fifth.

With chords that are adjacent, we have no common chord tones (the chord tone of the seventh excepted). And, if we were to follow our well established guideline of moving voices to the nearest chord tone by way of the shortest distance, we would yield uninteresting and unimpressive results: direct, parallel voice leading that also results in one of the most critical voice-leading problems for this style in which we are working: parallel octaves and parallel fifths.

Root position of any two adjacent chords is perhaps the most troublesome to handle when trying to avoiding perfect parallel motion in the voices. Using inversions in at least one of the chords being connected , however, will often aid the avoidance of voice-leading problems such as perfect parallel intervals, and may provide better, smoother results when voice-leading. The first inversion triad is especially useful for such connections.

Freer Treatment of Dissonance I: The Diminished Fifth

We’ve been very careful to prepare and resolve the harmonic dissonance of the diminished fifth, found in both the diminished triad and the two seventh chords containing a fifth chord tone which is diminished: the half-diminished seventh chord (a.k.a minor seven flat-five), and the “fully” diminished seventh chord. Now that we’ve become conscious of this interval and had practice in its preparation and resolution, we may now more flexibly and freely voice-lead the diminished fifth in these particular chords by no longer having to strictly prepare and resolve the diminished fifth dissonance. In short: as long as all of the other voice-leading is handled well, the diminished fifth may be introduced without any preparation and resolved freely (i.e. without having to move by stepwise motion downward).

Figure 4. Examples of freer treatment of the diminished fifth (in C Major)

There is, however, one very important restriction when handling diminished fifths more freely: While a diminished fifth my be held, moved into or out of by stepwise motion, or moved into or out of by a skip, the diminished fifth may not be leaped into or out of any voice. Doing so introduces instability and imbalance in the phrase.

Figure 5. Example of mishandling of the diminished fifth by voice-leading out of the dissonance by a leap (in this case, down a fourth).

The Relationship Between the Dominant Seventh Chord (Major-Minor Seventh) and Diminished Triad

There is an deep and intimate connection between the diminished triad and the major-minor seventh chord (a.k.a. Dominant seventh): In fact, they can be considered as one: The diminished triad is essentially an incomplete voicing of the major-minor (Dominant) seventh chord, having all but one tone in common:

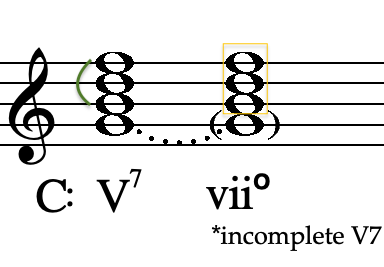

Figure 6. The differences and the similarities between a Dominant seventh chord (V7) and the leading-tone diminished triad (vii) in C major.

In the above example, we have a V7, Dominant seventh chord compared against a vii Leading-Tone triad in C major. As can be seen, the only real difference between the two chords is that the diminished triad is missing the root of the Dominant seventh. Any diminished triad may be considered an incomplete, rootless voicing of a Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord.

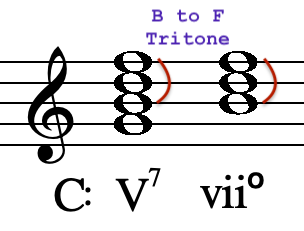

You may well ask: Isn’t voicing (hearing) the root of a chord important? Yes, of course the root of a chord is very important to voice and sound and, for most chords, especially chords that contain a stable perfect fifth, such as major and minor triads and major-major and minor-minor seventh chords, the root is all but essential to provide the proper context as to the nature and function of a chord in a tonal phrase of music. However, the diminished triad is different: it is somewhat ambiguous, consisting of two stacked minor thirds and, consequently, contains no stable perfect fifth. Thus, it is by nature not grounded by a stable perfect fifth. Instead it contains a diminished fifth, the tritone. The tritone, as we will explore more and more, has an inherently strong tendency to resolve, either inward or outward by stepwise motion. We find the exact same tritone in the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord, with exactly the same tendency for resolution and movement. Hence, these two chords, by virtue of containing the same tritone, are functionally equivalent. As such, may be substituted equally for one another. It does not matter if the chord tone of the root is voiced or not as it provides no substantive information. This voicing of the root, in this case, is purely a matter of tone color, not of function.

Figure 7. Showing the same tritone, here in C major between the Dominant (major-minor) seventh (V7) and Leading-Tone diminished triad (vii).

It should be noted that any diminished triad may be considered an incomplete major-minor seventh chord, and function as such. For example, the ii in the natural (Descending) minor can be thought of as a VII7 chord. Or, in the Ascending form of minor, the vi and vii chords may be considered as IV7 and V7 respectively.

Freer Treatment of Dissonance II: The Dominant (Major-Minor) Seventh

Above we learned that the diminished triad is, in fact, an incomplete (rootless) voicing of a Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord. And, since we also loosened the stricter guidelines on handling the dissonance of the diminished fifth, we may now, by extension, also loosen the handling of the dissonance in the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord since they are functionally the same. For now, the only seventh chord which may be treated more freely in terms of the guidelines involving preparation and resolution is the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord.

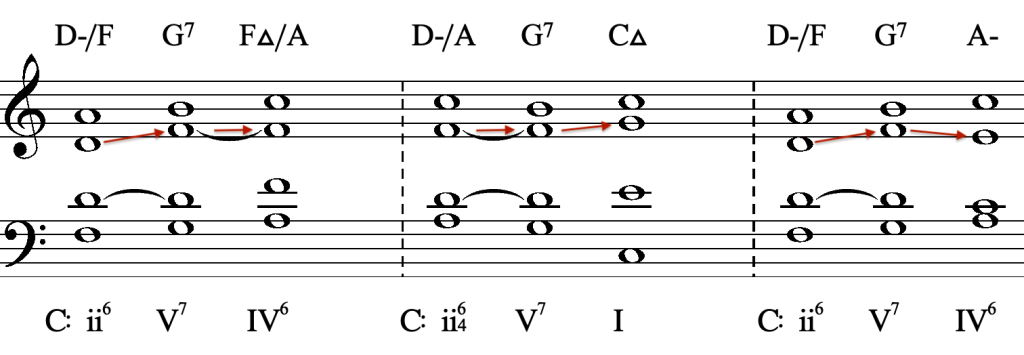

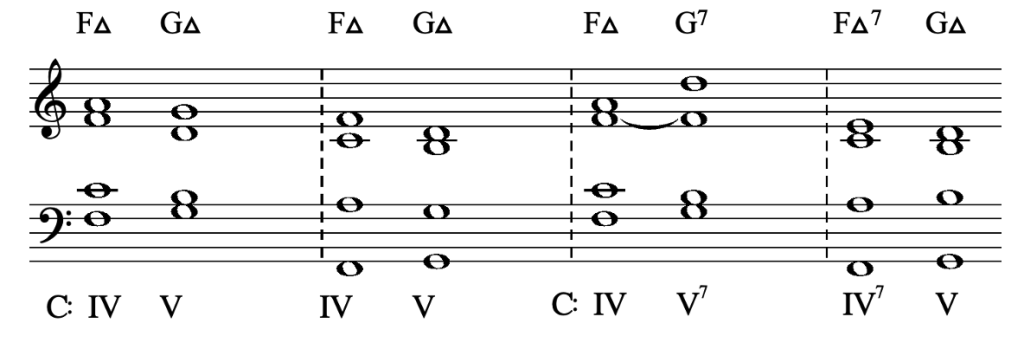

Figure 8. Several examples of the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord in a freer treatment of the dissonant tone (in C major).

We may handle the seventh in this particular chord with the same freedom as we now have with the diminished fifth in the diminished triad: The seventh may be held, moved into or out of by stepwise motion, or into our out of by a skip. However, the same restriction applies: The seventh may not be leaped into or out of any voice.

Voice-Leading Considerations I: Doubling

We should, when possible, still try to double the root of any triad, regardless of inversion, as it will give us the strongest representation of the chord. However, now that we have both freer treatment of dissonances (diminished fifth and the seventh in the major-minor seventh chord) and with the possibility of connecting chords that have no common tone (with roots adjacent to one another), it will sometimes be impossible to double the root when trying to avoid voice-leading problems such as perfect parallel intervals, voice crossing, etc. Thus we may more freely double chord tones in triads with the overarching purpose to achieve smoothness of line and good voice-leading. There are no hard and fast rules here, but a general rule of thumb is, when it is not possible to double the root, look to double the fifth in a first inversion triad and the third in a second inversion triad.

One important exception: Never double a dissonance.

Voice-Leading Considerations II: Omitting Tones

Seventh Chords: One should always strive to sound every tone in a seventh chord, sounding each chord tone in our four part SATB texture. However, with our newly introduced possibilities, it may be necessary and perhaps even advantageous to omit a chord tone from a seventh chord, especially so with the Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord. When doing so, the fifth may be omitted. You must, however, sound the root, third, and seventh of the chord as these three tones are necessary to define the nature and qualities of the harmony. This should be done seldomly and with care and attention.

Triads: Very rarely, and only with care, you may omit the fifth of a major or minor triad, and only the fifth as the root and the third are necessary to provide the nature and quality of the harmony. Again, this should only be done with all other options would lead to a voice-leading problem.

RWU EXERCISES

Major and Minor: Chord Connection with Non-Common Chord Tones and Freer Treatment of Dissonance

Using the templates below, do the following:

- Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, at least 7 to 12 chords in length:

- Two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice); two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

- Each phrase should have at least three seventh chords.

- Each phrase should have at least one example of a diminished triad or Dominant (major-minor) seventh chord using the freer guidance on handling dissonance.

- You may now connect chords together with no common tones (adjacent roots). However, do not have more than two of such in any phrase.

- Two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice); two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Schoenberg Theory of Harmony Examples

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

A melodic interval greater than a third (fourths, fifths, octaves, etc.)

A seventh chord in which the triad quality is major and the seventh quality is minor.

a voicing of a chord which does not contain its root, but still is able to function as if the root were present and sounding in the voicing.