Modal Counterpoint

3 Counterpoint: Second Species

Key Points

The second species of species counterpoint sees the counterpoint melody move twice as fast as the cantus firmus. This introduces the concept of strong and weak beats within a meter.

In second species, the harmonic interval between the counterpoint melody and cantus firmus on strong beats are always consonant. The harmonic interval formed between the counterpoint melody and the cantus firmus on weak beats may be either consonant or dissonant. Harmonic dissonance may occur on weak beats through passing motion in the counterpoint melody. Harmonic consonances on weak beats connect two consonant strong beats to create a succession of 3 consonances. Examples of such melodic motion may be of many types:

- A consonant passing tone: two steps in the same direction to outline a third.

- A substitution: leap a fourth, then step in the opposite direction.

- A skipped passing tone: a third and a step in the same direction to outline a fourth.

- An interval subdivision: two leaps in the same direction to divide a larger melodic interval, for example, with two thirds to make a fifth.

- A change of register: a large, consonant leap (perfect fifth, sixth, or octave) from strong beat to weak beat, followed by a step in the opposite direction.

- A melodic delay: leap a third, then step in the opposite direction.

- A consonant neighbor tone: step in one direction, then step back to the original tone.

In second species counterpoint, we introduce rhythm by way of a simple meter where the counterpoint melody moves in half notes against a given cantus firmus written in whole notes. This 2:1 rhythmic ratio leads us to two new “fundamental musical problems”—one metric and one harmonic: the differentiation between strong beats and weak beats, and the introduction of harmonic dissonance through passing tones. The introduction of harmonic dissonance into second species adds to the variety and overall interest of the musical texture. However, it brings musical tension that should be balanced with consonance to promote coherence and logic. Thus, handling such dissonance requires careful attention.

Here are examples of second species counterpoint from Part I of Gradus ad Parnassum, annotated (as with first-species) with the interval that the counterpoint line makes with the cantus firmus.

Second Species Examples from Gradus ad Parnassum

The Counterpoint Line

As in first species, the counterpoint line should be singable and have a good shape, with a single climax and primarily stepwise motion with a few skips and the occasional leap (for variety or to potentially solve a possible problem). However, because a first-species counterpoint had so few notes, in order to maintain the overall smoothness in other aspects of the exercise, the counterpoint melody of first species will often engage in skips. In second species, however, the increase in the total number of counterpoint melody notes and the added freedom involving the use of dissonance makes it easier to move in smoother, stepwise motion without creating additional problems. Thus, a second species counterpoint is even more dominated by stepwise motion than a first species counterpoint. If the counterpoint melody must skip or leap, do take advantage of the metrical arrangement (the placement of both weak and strong beats) to diminish the attention which is drawn by such a skip or leap. For instance, leap from a strong beat to a weak beat rather than from a weak beat to a strong beat (crossing over the point where the cantus firmus changes) when possible. Also, because there are more notes in a second species counterpoint melody, there are usually one or two secondary climaxes—notes lower than the overall climax—serving as “local” climaxes for portions of the line. This will help the integrity of the counterpoint melody by ensuring that it has a coherent shape and does not simply wander around aimlessly.

Beginning and Ending

Beginning a second species counterpoint

As in first species, begin a second species counterpoint melody above the cantus firmus with do, scale degree ![]() or sol, scale degree

or sol, scale degree ![]() . Begin a second species counterpoint below the cantus firmus with do, scale degree

. Begin a second species counterpoint below the cantus firmus with do, scale degree ![]() .

.

A second species counterpoint melody may begin with two half notes in the opening, or it may begin with a half rest followed by a half note. Beginning with a half rest establishes the rhythmic profile and independence of the counterpoint melody more readily, making it easier for the listener to parse, and a little easier to compose, so it is often preferable; however, it is by no means required. Regardless of the chosen opening rhythm, the first pitch in the counterpoint should follow the harmonic interval guidelines above.

Ending a second species counterpoint

As in first species, you should end with a clausula vera: the final pitch of the counterpoint should be do, scale degree ![]() ; the penultimate note of the counterpoint melody should be ti, scale degree

; the penultimate note of the counterpoint melody should be ti, scale degree ![]() if the cantus is on re, scale degree

if the cantus is on re, scale degree ![]() , and the melody should be re, scale degree

, and the melody should be re, scale degree ![]() if the cantus is on ti, scale degree

if the cantus is on ti, scale degree ![]() .

.

The penultimate bar of the counterpoint may either be a whole note (making the last two bars identical to first species) or it may be made of two half notes. This allows you to begin your clausula vera on either the strong beat or the weak beat of the penultimate measure.

Strong Beats

The inclusion of dissonance in a musical texture creates new musical issues that need attention. Because the pedagogical philosophy of species counterpoint is to present only a small number of new musical problems with each successive species, second species counterpoint introduces the concept of dissonance in a very limited way.

Strong beats (downbeats in second species) are always consonant. As in first species, prefer imperfect consonances (thirds and sixths) over perfect consonances (fifths and octaves), and avoid unisons.

Because motion across bar lines (from weak beat to strong beat) involves the same kind of voice motion as first species (i.e. the two voices moving simultaneously), follow the same guidelines and principles we learned in first-species counterpoint. For instance, if a weak beat is a perfect fifth, the following downbeat cannot also be a perfect fifth (this would give us parallel motion with perfect intervals which is not allowed in first species guidelines).

Likewise, progressions from downbeat to downbeat must also follow the principles of first-species counterpoint described in the previous chapter, such as:

- Do not begin two consecutive measures with the same perfect interval.

- Do not outline a dissonant melodic interval between consecutive downbeats. (Exception: if the counterpoint leaps an octave from the strong beat to the weak beat, the leap should be followed by step in the opposite direction, making a seventh with the preceding downbeat. This is okay, since it is the result of smooth voice motion.)

- Do not begin more than three bars in a row with the same imperfect consonance.

In other words, if you remove the weak beat of the counterpoint melody, your phrase should conform to the guidelines of first species. However, hidden or direct fifths/octaves between successive downbeats are fine, as the effect is softened by the intervening note in the counterpoint melody.

Weak Beats

Since harmonic dissonances may now appear on weak beats, a mixture of consonant and dissonant intervals on weak beats is the best way to promote variety and sustain interest.

Unisons were problematic in first species because they diminished the independence of the melodic lines. However, when they occur on the weak beats of second species and are the result of otherwise smooth voice leading, the rhythmic difference in the two lines is sufficient to maintain a sense of linear independence. Thus, unisons are permitted on weak beats when necessary to make good counterpoint between the lines.

Any weak-beat dissonance must follow the pattern of a dissonant passing tone, explained below. Also explained below are a number of standard patterns found on consonant weak beats. Chances are high that if your weak beats do not fit into one of the following patterns, there may be a problem with your counterpoint melody, so use them as a guide both for composing the counterpoint meldoy and for evaluating it.

These principles should help guide your use of weak-beat notes in a second species counterpoint melody. A good general practice is to start with a downbeat note, then choose the following downbeat note, and finally choose a pattern below that will allow you to fill in the space between downbeats well.

Most of these principles are used as examples in the demonstration video at the bottom of the page.

Dissonant passing tones (weak beats only)

All dissonant weak beats in second species are dissonant passing tones, so called because the counterpoint meldoy passes from one consonant downbeat to another consonant downbeat by stepwise motion. The melodic interval from downbeat to downbeat in the counterpoint will always be a third, and the passing tone will come in the middle in order to fill that third with passing motion.

Since all dissonances in second species are passing tones, you will not skip or leap into or out of a dissonant harmonic interval, change directions on a dissonant tone, nor write a dissonance on a downbeat.

Consonant weak beats

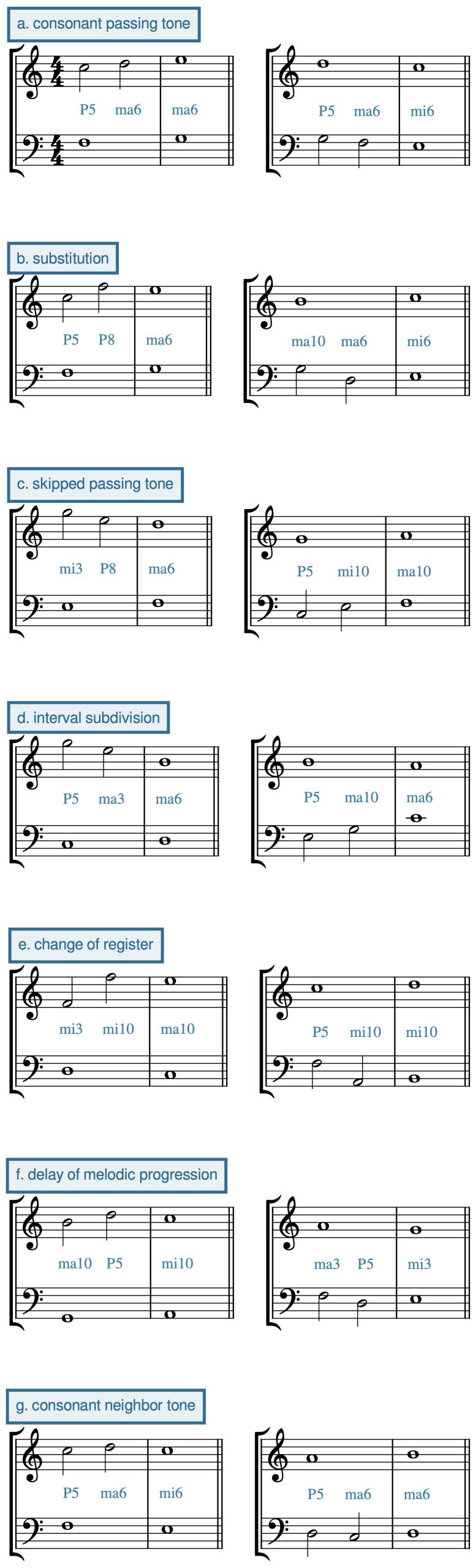

Unlike dissonant weak beats (of which there is only one type), there are several types of consonant weak beats available (Example 2):[1]

-

- A consonant passing tone outlines a melodic third from downbeat to downbeat, and it has the same pattern as the dissonant passing tone, except that all three tones (downbeat, weak beat passing tone, downbeat) are consonant with the cantus firmus. A consonant passing tone will always be a sixth or perfect fifth above/below the cantus firmus.

- A substitution also outlines a third from downbeat to downbeat. However, instead of filling it in with stepwise motion, the counterpoint leaps by a fourth and then steps in the opposite direction. It is called a substitution because it can substitute for a passing tone in a line that needs an extra leap or change of direction to provide variety. Like the consonant passing tone, all three notes in the counterpoint melody must be consonant with the cantus firmus.

- A skipped passing tone outlines a fourth from downbeat to downbeat. The weak-beat note divides that fourth into a third and a step. Again, all three intervals (downbeat, skipped passing tone, downbeat) are consonant with the cantus firmus.

- An interval subdivision outlines the melodic distance of a fifth or sixth between successive downbeats. The large, consonant melodic interval between downbeats is thus divided into two smaller consonant skips/leaps. A melodic fifth between downbeats would be divided into two skips (thirds). A melodic sixth between downbeats would be divided into a skip of a third and a leap of a fourth (either direction). Not only must all three melodic intervals be consonant (both note-to-note intervals and the downbeat-to-downbeat interval), but each note in the counterpoint must also be consonant with the cantus firmus.

- A change of register occurs when a large, consonant leap (a perfect fifth, sixth, or octave) from strong beat to weak beat is followed by a step in the opposite direction. It is used to achieve melodic variety after a long stretch of stepwise motion, and/or to avoid problematic parallel harmonic motion, or other issues, or to get out of the way of the cantus to maintain independence (i.e. not cross voices). Since this motion is very strong, it should be used infrequently. And as always, each note must be consonant with the cantus firmus.

- A delay of melodic progression outlines a step (up or down) from downbeat to downbeat. This type of melodic motion involves a skip of a third from strong beat to weak beat, followed by a step in the opposite direction into the following downbeat. It is called a “delay” because it is used to embellish what otherwise is a slower first-species progression (motion by step from downbeat to downbeat).

- A consonant neighbor tone occurs when the counterpoint melody moves by step from downbeat to weak beat, and then returns to the original pitch on the following downbeat. If the first downbeat makes a fifth with the cantus, the consonant neighbor will make a sixth, and vice versa.

EXAMPLES

Second Species in DORIAN, PHRYGIAN, LYDIAN

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

EXERCISES

Second Species Counterpoint

- Exercise #3 (CP3): Dorian 2nd Species (x2)

- Exercise #4 (CP4): Lydian and Phrygian 2nd Species (x2 each)

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Further Reading

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

- The terms used here are either standard or taken from Salzer & Schachter’s "Counterpoint in Composition". ↵

A traditional approach to music composition pedagogy focused on counterpoint as a way of learning to think of music horizontally (melodically) and vertically (harmonically) simultaneously. Consists of five “species,” each of which focuses on a single compositional element.

Literally meaning “fixed voice," this is a pre-existing melodic line that serves as the basis for a new counterpoint exercise or other composition.

A recurring pattern of accents that occur over time. Meters are indicated in music notation with a time signature.

An interval whose notes sound together (simultaneously).

In a given meter, it is beat which is stressed (given emphasis).

A perceived stability or smoothness in a chord or interval relative to the surrounding musical texture.

In a given meter a beat that is unstressed (not emphasized).

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord, relative to the surrounding musical texture.

Passing melodic motion that does not involve dissonance.

In counterpoint, a type of consonant weak beat that involves a melodic leap of a fourth followed by a step in the opposite direction. The name implies that this motion substitutes for a more common passing-tone motion.

In counterpoint, a type of consonant weak-beat melodic motion that is approached by skip (third) and left by step in the same direction.

In counterpoint, a type of consonant weak beat melodic motion that divides a larger consonant leap (from downbeat to downbeat) into two smaller leaps.

In counterpoint, a type of consonant weak beat melodic motion that steps in the opposite direction following a large leap.

In counterpoint, a type of consonant weak beat melodic motion that skips by third and then steps into the following downbeat.

Embellishing melodic tones that are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction.

The domain of musical time through meter and pulse

The vertical dimension of music formed, often formed by two or more intervals sounding together (dyads, chords, etc.) and the relative relationships of the partials of the harmonic series of sounding voices and instruments.

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord.

A type of motion where a chord tone moves by step to another tone, then resolves by step in the same direction. For example, C–D–E above a C major chord would be an example of neighboring motion, in which D can be described as a passing tone. Entire harmonies may be said to be passing when embellishing another harmony, when the voice-leading between the two chords involves mainly passing tones (as in the passing 6/4 chord).

As an acoustic phenomenon, frequencies vibrating at whole-number ratios with one another; as a cultural phenomenon, perceived stability in a chord or interval.

A contrapuntal ending (cadence) in which a perfect octave or unison is approached with contrary motion in the voices by stepwise motion. One line will have re–do (2̂– 1̂) while the other will have ti–do (7̂-1̂). This results in the sequence of harmonic intervals sixth–octave, tenth–octave, or third–unison. The effect is one of closure and ending.

Second-to-last

Beat 1 of any measure, which, when conducted, is conducted with a downward motion.

Thirds or sixths with major or minor quality. These intervals are found in higher overtones in the harmonic series from a given fundamental and have a more distant relationship in terms of frequency ratios.

Perfect octaves (twelve semitones), perfect unisons (zero semitones), and perfect fifths (seven semitones). Perfect fourths (five semitones) are sometimes considered a perfect consonance, sometimes a dissonance; this depends on the context.

A type of voice motion when two voices move in the same direction in relation to each other and move by the same melodic interval and, thus, retain the same harmonic interval—for example, both voices move upward by a melodic second.

melodic motion to the next adjacent note (pitch) in the mode/scale (scale degree), either up or down.

An interval whose notes are sounded separately (one note after another).

Melodic movement by third.

A melodic interval o greater than a third.