Western Harmonic Practice II: Chromaticism and Extended Tonality

17 Chord Borrowing I: The Secondary Dominant

Key Takeaways

Chord borrowing is a fundamental harmonic technique in tonal music, allowing for the use of chords from closely related keys without changing the original key’s tonal center. This chapter explores the concept of chord borrowing, particularly focusing on secondary dominants, their purpose, and guidelines for their use.

Borrowing Chords

- Involves substituting a chord from a closely related key for a diatonic chord within a given scale degree.

- Does not alter the original key or tonal center, unlike modulation.

- Adds contrast, emotional depth, and color to music.

- Traditionally used in specific contexts, like the secondary dominant, during the common practice period.

Closely Related Keys

- Defined as keys associated with secondary scale degrees (

to

to  ) of the primary key.

) of the primary key. - The diminished triad scale degree (diatonic locrian mode) is not considered stable for establishing a key.

The Secondary Dominant

- A Dominant chord (triad or seventh) borrowed from a secondary scale degree within the primary key.

- Functions similarly within its key area, providing a Dominant harmonic function relative to the secondary key.

- Typically leads to a common cadential pattern, either an Authentic or Deceptive Cadence.

- Can replace any diatonic triad or seventh chord if they tonicize a valid secondary key area.

- The use of secondary dominants should be moderated to avoid destabilizing the primary key.

Introduction: Understanding Chord Borrowing

Chord borrowing is a harmonic technique used in tonal music that involves substituting a chord from a closely related key for another diatonic chord within a the key area of a secondary scale degree. This technique represents is a basic form of chord substitution. Unlike modulation, which aims to shift the key of the music either permanently or for a large portion or section, chord borrowing introduces chords from other keys without altering the original key or tonal center. Tonal music often explores different tonal regions while maintaining a connection to the main key and tonal center. Another term often used for a borrowed chord is applied chord.

Closely Related Keys

In the context of this discussion, a closely related key is defined as one associated with a secondary scale degree of the primary key, specifically degrees ![]() to

to ![]() . It’s important to note that the secondary scale degree in either the major or minor mode which forms a diminished triad (i.e. diatonic locrian mode) is not considered a stable tonal key and therefore is never used as a possible secondary key area.

. It’s important to note that the secondary scale degree in either the major or minor mode which forms a diminished triad (i.e. diatonic locrian mode) is not considered a stable tonal key and therefore is never used as a possible secondary key area.

The two charts below illustrate the secondary key areas for both major and minor modes, Additionally, borrowing from a secondary minor key area includes chords from the raised form of the minor scale.

Secondary Key Areas: Major Mode

| Diatonic Modal Area | Diatonic Triad | Tonal Key Area | Example (in C major) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TONIC | Ionian Major | I | Tonic Major | C Major |

| SUPERTONIC | Dorian Minor | ii | SuperTonic Minor | D Minor |

| MEDIANT | Phrygian Minor | iii | Mediant Minor | E Minor |

| SUBDOMINANT | Lydian Major | IV | SubDominant Major | F Major |

| DOMINANT | Mixolydian Major | V | Dominant Major | G Major |

| SUBMEDIANT | Aeolian Minor | vi | SubMediant Minor | A Minor |

| LEADING-TONE | Locrian | vii | Not A Stable Key Area | Not A Stable Key Area |

Secondary Key Areas: Minor Mode

| Diatonic Modal Area | Diatonic Triad | Key Area | Example (in C Minor) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TONIC | Aeolian Minor | i | Tonic Minor | C Minor |

| SUPERTONIC | Locrian | ii | Not A Stable Key Area | Not A Stable Key Area |

| MEDIANT | Ionian Major | III | Mediant Major | E Major |

| SUBDOMINANT | Dorian Minor | iv | SubDominant Minor | F Minor |

| DOMINANT | Phrygian Minor | v | Dominant Minor | G Minor |

| SUBMEDIANT | Lydian Major | VI | SubMediant Major | A Major |

| SUBTONIC | Mixolydian Major | VII | SubTonic Major | B Major |

Chord borrowing serves various purposes, such as adding contrast, emotional depth, or color to the music. However, during the common practice period of Western tonal music, its use was often restricted to specific uses, such as the secondary dominant.

Voice-Leading Borrowed Chords

Borrowed chords will introduce one or more tones that do not belong to the primary key (i.e. non-diatonic to the primary key). Any non-diatonic tone should be introduced through diatonic melodic voice-leading, thinking at least locally within the context of the secondary key from which the chord(s) is borrowed. Except for the tritone, melodic intervals should be handled cautiously and you should avoid the use of augmented or diminished melodic intervals in your writing. Also, at this stage, chromatic voice-leading remains prohibited.

The Secondary Dominant

The secondary dominant refers to a Dominant chord, triad or seventh, borrowed from a secondary scale degree within the primary key. This chord functions similarly to how it would within its own key area, thus has a Dominant harmonic function relative to the secondary key. This process of locally emphasizing a secondary scale degree as a localized tonic is known as tonicization. Consequently, the chord progression involving a secondary dominant typically follows a common cadential pattern, such as that found in an Authentic Cadence (Dominant ![]() Tonic) or a Deceptive Cadence (Dominant

Tonic) or a Deceptive Cadence (Dominant ![]() Submediant or Subdominant). The resolution chord can be another borrowed chord or represent a return to a diatonic chord within the primary key.

Submediant or Subdominant). The resolution chord can be another borrowed chord or represent a return to a diatonic chord within the primary key.

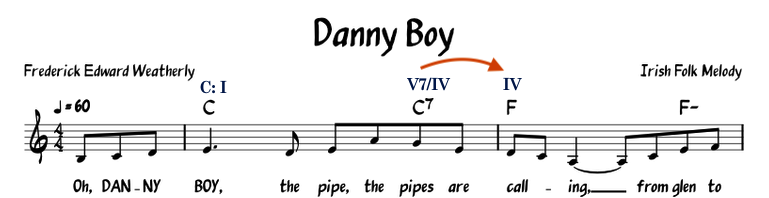

The use of secondary dominants is quite common not only in classical music but in many popular and folk songs. For example, the opening of the Irish folk song “Danny Boy” features a secondary dominant to the SubDominant Major in the very first phrase:

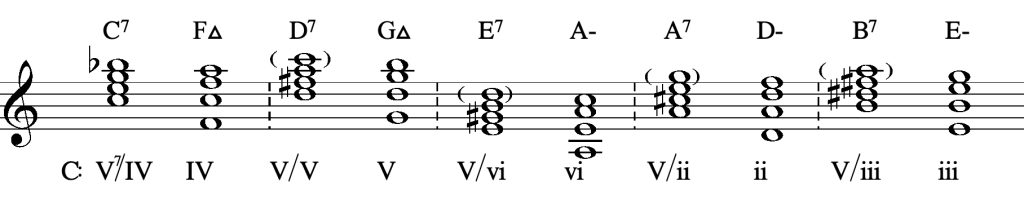

Secondary Dominants in Major

The example below demonstrates the available secondary dominants in the major mode, using C major as the reference key. Here, all dominants proceed to the tonic in an authentic harmonic movement. This illustrates one possible approach, although alternative paths, such as the Deceptive cadential model, could also be used.

The introduction of these new chords is unproblematic as long as the voice-leading is handled properly and the chord’s functional role as a Dominant to the secondary key area is respected.

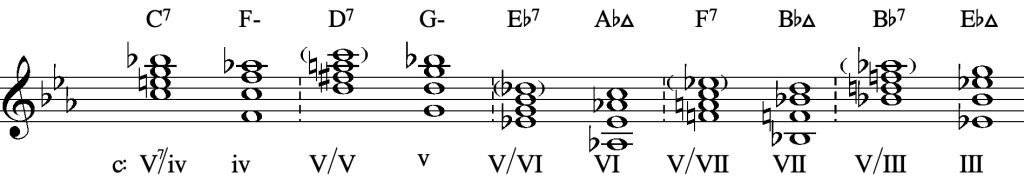

Secondary Dominants in Minor

The process of deploying secondary dominants in the minor mode is very similar to that of the major mode. A few of these secondary chords are already known by way of the raised form of minor. In this context, however, we are to treat these chords as secondary dominants with a dominant function in the secondary, tonicized key area. In the example below, we have the secondary dominants in minor and, as with the examples in the major mode above, all dominants proceed to the tonic in an authentic harmonic movement; alternative paths, such as the Deceptive cadential model, could also be used.

Since the minor mode has special voice-leading considerations with respect to the raised form of the mode, we do need to be mindful of this when using these chords in minor. However, when using secondary dominants in a progression, the guidelines for handling the pivot-tones in minor are superseded by the voice-leading guidelines found here.

Secondary Dominants: Basic Guidelines

- Secondary Dominants can replace any diatonic triad or seventh chord, provided they tonicize a valid secondary key area relative to the primary key (consult the provided charts for clarity).

- Integrate any non-diatonic tones from the borrowed chord through smooth diatonic melodic motion, avoiding augmented or diminished intervals, except for the tritone.

- Handle non-diatonic tones similarly to pivot tones in the Minor Mode, especially the artificially introduced leading-tone of the secondary key area, which should ideally ascend to the tonicized secondary scale degree.

- In the Minor Mode, the primary key’s pivot tone guidelines may be overridden by the above voice-leading requirements.

- While the use of secondary dominants is at the composer’s discretion, moderation is advised so as not to destabilize the primary key. The use of many secondary dominants may necessitate a strong cadence to help firmly re-establish the primary key and restore balance.

EXAMPLES: Secondary Dominants

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

RWU EXERCISES

Using Secondary Dominants

Using the template below, please do the following:

1. Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, MAJOR MODE of at least 8 to 12 chords in length:

-

- Use at least two (2) secondary dominants in each phrase

- Try different approaches, some as triads, some as sevenths.

- Try different resolutions (i.e. to the secondary tonic chord or mimicking a deceptive resolution)

Exercise 270 #2: (PW-2): Secondary Dominants (Major)

2. Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, MINOR MODE of at least 8 to 12 chords in length:

-

- Use at least two (2) secondary dominants in each phrase

- Try different approaches, some as triads, some as sevenths.

- Try different resolutions (i.e. to the secondary tonic chord or mimicking a deceptive resolution)

Exercise 270 #3: (PW-3): Secondary Dominants (Minor)

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Schoenberg Theory of Harmony Examples

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

Replacing a standard chord (i.e., within a harmonic schema) with a different chord. The substituted chord is typically identical in harmonic function to the standard chord, and often shares at least two notes with the standard chord.

A change of key.

A chord from another key inserted into a new key, in order to tonicize a diatonic chord other than I.

Melodic motion in a given voice wherein the primary note letter name remains the same but the accidental inflection is changed. Example: C to C-sharp is a chromatic half-step as opposed to C to D-flat which is a diatonic half-step.

A chromatic chord that temporarily tonicizes another key besides the tonic key, by taking on a dominant function in that new key.

Refers to three categories of chords: tonic, predominant, and dominant. A chord's membership within a category indicates something about how that chord typically behaves in tonal harmonic progressions in Western classical music. For example, tonic function chords are stable and tend to represent points of resolution or repose.

The process by which a non-tonic triad is made to sound like a temporary tonic. It involves the use of secondary dominant or leading-tone chords.