Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

8 Chord Inversions (Triads)

Key Points

Here we learn about, and to work with the two inversions of the triad.

- The First Inversion (The “Six Chord”):

- A triad with the third chord tone voiced in the bass, labeled in figured bass notation with a superscript “6” (hence the name “Six Chord”) and labeled in lead sheet chord notation with the parent chord followed by a slash “/” and the pitch class of the sounding bass note.

- A softer, less focused version of the root position version of the triad owing to the distant relationship the bass tone’s overtones has in relationship the sounding chord tones.

- May be use freely and wherever a root position triad would be used (except the beginning and ending of a musical phrase)

- Is often used to produce a voice exchange.

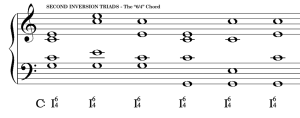

- The Second Inversion (The “Six-Four Chord”):

- A triad with the fifth chord tone voiced in the bass, labeled in figured bass notation with a superscript “6/4” (hence the name “Six-Four Chord”) and labeled in lead sheet chord notation with the parent chord followed by a slash “/” and the pitch class of the sounding bass note.

- A harsher, grittier sounding version of the root position version of the triad owing to the conflict between the bass tone’s overtones in relationship with the sounding chord tones. The primary conflict being the interval of the fourth formed between the bass voice and root of the chord which causes instability. Because of this, the bass tone needs to be carefully voice lead by sustained or common tones, or by stepwise motion to and from this chord.

- Should be used sparingly and only in specific situations in a musical phrase:

- As a passing chord connecting two root position chords a third apart.

- An indirect voice exchange placed between two chords on the same scale degree, one in root position and the other in first inversion.

- In the cadence of a musical phrase as a dominant prolongation chord (to be explained in a later chapter).

With this greater flexibility and additional choices comes a greater risk of voice leading problems. Therefore more attention and care needs to be exercised to avoid the writing of perfect parallel intervals (fifths and octaves) between the voices and other problems such as voice crossing and spacing issues.

In this chapter we will learn how to both incorporate and handle inverted triads, when the bass voice in our SATB texture contains a chord tone other than the root. These inverted voicings of the triad have different properties and qualities in terms of sound and, as a result, change our perception of the musical flow in a chord progression. Because of these differences, we need to learn how these voicings are often treated in songs and compositions.

The Acoustics (Sound) of Inverted Chords

As was explained in more detail in the section on Acoustics and Psychoacoustics [1], the harmonic series in physics is the governing mechanism, or natural law of sound. This series, which in music is also referred to as the overtone series is especially important when considering a periodic sound wave which we perceive through the mechanics of perception and psychology as a single, stable pitch. Even though we do not hear each overtone frequency as a discrete pitch, they all blend together perceptually to create what we call timbre: sound quality or sound color. When two or more tones sounding, the overtones of each sounding pitch are all relating to one another creating an overall sense of acoustic sound texture which includes our relative perception of consonance and dissonance, chord quality, and so on.

A good example of how the overtone series sounds, up to the 16th harmonic (four octaves) may be heard here:

For now, we can boil all of this down to one important psycho-acoustical axiom: the lowest sounding tone of an interval or chord, by virtue of its position as the lowest in the sounding texture, will always be perceived as the fundamental tone and, as a result, that tone’s harmonic series will attempt to imprint itself upon the other sounding tones in our brains. We hear those relationships of tone vs overtones acutely in a paradigm of increasing or decreasing levels of acoustic roughness. The figure below shows a C major triad, voiced in a SATB chorale style texture with the root doubled, in root position, first inversion, and second inversion with the bass note’s overtone series mapped against the sounding chord tones.

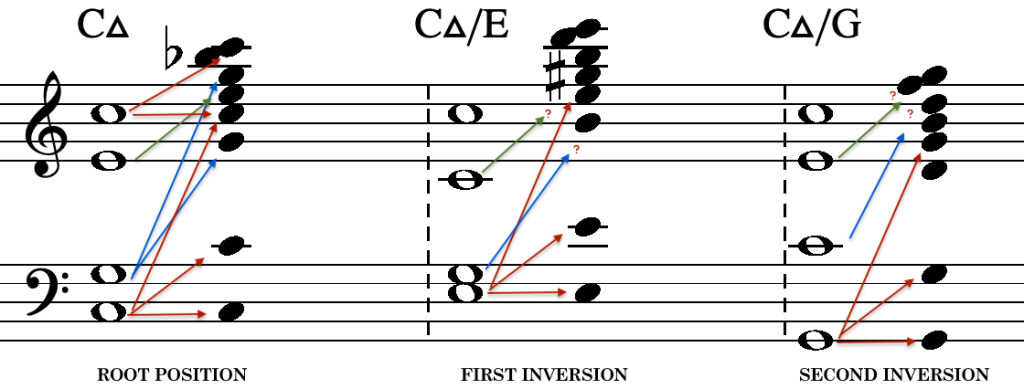

Figure 1. Triad chord inversions and bass overtones in relationship

The arrows in the figure show the sounding tones (open whole note heads) mapping to the overtones of the bass note (filled in noteheads). One can see how the root position voicing is very resonant and focused, with the bass tone and the it’s overtones often overlapping and repeating. When we place a different chord tone in the bass, creating an inversion, the sound becomes less clear and less resonant in relationship to the overtones of the bass voice. The following two observations may be made by way of the examples above:

- The first inversion chord tries to sound like some type of chord rooted on the bass voice pitch E (E major), while the sounding tones of C major in the voicing are in opposition. The result is a softer, less focused C major chord that almost sounds like an E minor chord, but not quite.

- The second inversion presents us with a stronger relationship to the bass voice’s overtones of G but with this increased level of focus comes an even harsher contrast against the sounding chord tones. As a result, we have a more tense feeling as the overtones of the bass voice is almost overpowering the sounding chord tones of C major above. Because of this conflict, the second inversion triad needs a bit more care and attention in use than the first inversion triad.

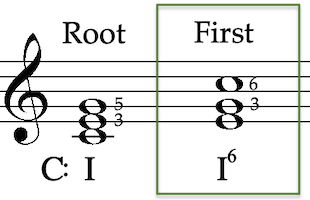

The First Inversion Triad: The “Six” Chord

The first inversion triad, with the third chord tone in the bass, is also called a “Six” (6) chord in Roman numeral notation with figured bass notation. Figured bass numbers refer to the intervals that the chord tones form above the given bass note. The figure below shows us how we arrive at this figured bass number by measuring the relative distance of the upper two chord tones from the bass: the fifth and the root, a third and sixth above the bass tone respectively.

Figure 2. The first inversion triad, the “6/3” or plain “6” chord. C major shown for example.

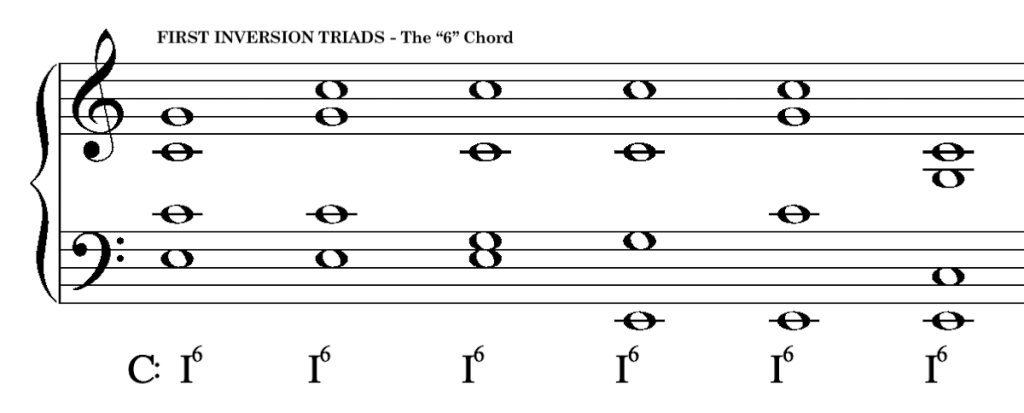

Technically, the figured bass should read “6/3” but practice has evolved in such a way that the “3” is dropped leaving us with only the number 6, hence the name “Six Chord.” It is very important to note that figured bass is not a literal measurement of a specific interval for tones to appear about the bass note for the purpose of voicing a chord, but rather is given as an abstract shorthand to indicate that we are to have chord tones in the harmony found at those intervals in pitch classes above the pitch class of the bass voice. The example below shows six different voicings of a C major triad in first inversion, however we still only label each of these chords simply as a “Six Chord.” The Roman numeral is there, as usual, to show us the scale degree in the indicated tonal center (key) upon which the chord is built. In this example, we are in C major with C as our tonal center and the Roman numeral I tells us we are building a chord on scale degree ![]() .

.

Example 1. Different voicings of a first inversion triad (the “Six / or 6” chord).

Voice Leading The “Six” Chord

The first inversion triad, the “Six” chord, while not as stable and focused as a root position triad, may be used freely, and can appear anywhere a root position triad might otherwise appear. The only exception to this is at the beginning or ending of a phrase which must always contain a root position triad. We can summarize with the following guidelines:

- First inversion chords may be used freely and can be substituted for root position chords for the sake of creating variety and providing smoothness in the bass voice melody

- Common uses of the first inversion triad is that as a passing chord between two root position chords or to engage in what is known as a voice exchange.

- It is permissible to connect more than one first inversion chord to another in a phrase. However, as with most things we have learned thus far, it is best to employ a “three strikes and you are out” strategy. Too much of a good thing is still too much.

- Occasionally, in order to avoid problems like voice leading between chords that would result in parallel perfect intervals (fifths and octaves), it is perfectly allowable to not always adhere the guideline to hold over common tone(s) or even move the voices in the shortest possible distance. However, always try the hold over common tones and move with the shortest possible distance wherever possible and only stray from this practice to avoid larger problems.

- Doubling: As before, it is best to double the root of the chord to help provide a more solid identity for the harmony. Exceptions to this guideline will be covered below.

- Labeling: When labeling first inversion chords, use the superscript “6” in the Roman numeral analysis as shown below. For the lead-sheet chord symbols, use a convention we refer to as “slash” notation where the chord is labeled as usual followed by a ”/” and then the pitch class of the bass note is indicated. For example, a first inversion C major chord would be labeled as C/E (or C/E or Cmaj/E, etc.)

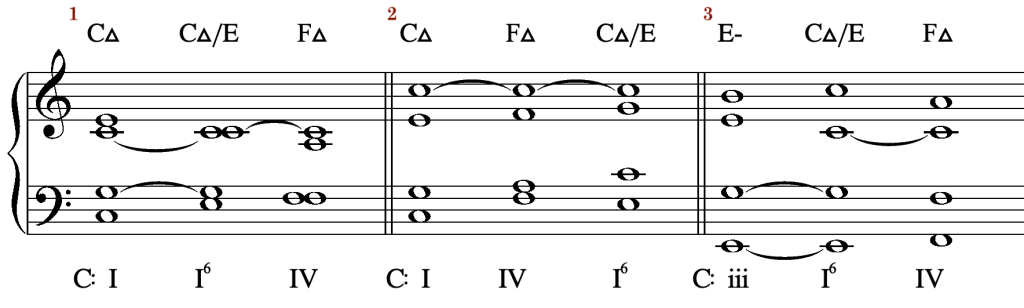

The example below gives us three common uses of the first inversion “Six Chord” triad in context:

- Direct Voice Exchange: Here we have a change of voicing while keeping the same harmony. The exchange of voices occurs when the soprano and bass exchange chord tones (E to C in soprano and C to E in bass).

- Indirect Voice Exchange: Here we have another change of position in the C major chord, but in this example there is another chord in between helping the voice leading in the alto voice, providing more variety.

- Passing Chord: Here the first inversion chord acts as a bridge between two other chords, in this case a move from iii to IV is facilitated by a passing I6 chord. Later, when we are able to connect chords on adjacent scale degrees, the first inversion “Six” chord will be very helpful in achieving smooth voice leading results and help to lower the chance of writing perfect parallel intervals between the voices.

Example 2. Examples of common first inversion “Six” chord uses.

The Second Inversion Triad: The “Six-Four” Chord

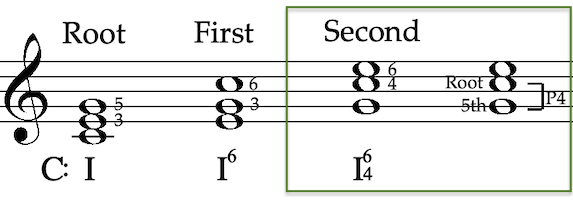

The second inversion triad, with the fifth chord tone in the bass, is also called a “Six-Four” (![]() ) chord in Roman numeral notation with figured bass notation. As with the “six” chord, the figure below shows how we arrive at this number by measuring the relative distance of the upper two chord tones from the bass: the third and the root, a sixth and fourth above the bass tone respectively.

) chord in Roman numeral notation with figured bass notation. As with the “six” chord, the figure below shows how we arrive at this number by measuring the relative distance of the upper two chord tones from the bass: the third and the root, a sixth and fourth above the bass tone respectively.

Figure 2. The second inversion triad, the “6/4” chord. C major shown for example.

Again, it is very important to note that figured bass notation is not a literal measurement of a specific interval for tones to appear about the bass note for the purpose of voicing a chord, but rather is given as an abstract shorthand to indicate that we are to have chord tones in the harmony found at those intervals in pitch classes above the pitch class of the bass voice. The example below shows six different voicings of a C major triad in second inversion, all labeled as a “6/4” chord in the figured bass notation. The Roman numeral shows us the scale degree in the indicated tonal center (key) upon which the chord is built. As with the above example of the first inversion triad, in this example we are in C major, with C as our tonal center, and the Roman numeral I tells us we are building a chord on scale degree ![]() .

.

Example 3. Different voicings of a second inversion triad (the “Six-Four” chord).

Voice Leading The “Six-Four” Chord

The second inversion triad is far less stable than the first inversion triad as the bass note is more at odds with the sounding chord tones. This tone is so strong that, as we will learn later, in the cadence we will often consider this chord’s root as the bass note rather than the root present in the sounding chord tones. As a result, this chord must be handled with more care and consideration than that of the root position or first inversion triad. In fact, in older music theory texts, the second inversion triad is often considered a dissonance chord owing to the tension formed between the bass note and the root of the chord which has an interval relationship of a fourth. As you recall, the fourth in strict counterpoint, like species counterpoint, is considered a dissonance. For our purposes, we do not need to think of the second inversion triad this strictly but it will be important to handle the voice leading, specifically the bass voice melodic motion with greater care. We can summarize with the following guidelines:

- Second inversion chords should be used sparingly, and only in specific situations (explained below). Otherwise the chord will have a tendency to throw off the balance of the harmonic progression and possibly destabilize the feeling of the tonal center.

- When using this chord, you must not leap or skip into or out of the bass voice of the chord. Only use the following voice leading to and from the bass voice: stepwise motion into and/or out of (above or below), tied or repeated notes into and/or out of, or octave motion (effectively the same as a tied note, changing the register).

- Common uses of the second inversion triad are similar to that of first inversion: a passing chord between two root position chords or passing chord between two of the same chord, engaging in a voice exchange (often moving from root position to first inversion or visa-versa).

- For now, avoid connecting two second inversion triads together because of the unstable nature of the chord.

- Doubling: Always double the root of the chord to help provide a more solid identity for the harmony. Only in very rare situations would you double another chord tone and only to avoid another significant voice leading problem. Exceptions to this guideline will be covered below.

- Labeling: When labeling second inversion chords, use the superscript “6/4” in the Roman numeral analysis as shown below. For the lead-sheet chord symbols, use “slash” notation as we did in the case of first inversion triads, where the chord is labeled as usual followed by a ”/” and then the pitch class of the bass note is indicated. For example, a second inversion C major chord would be labeled as C/G (or C/G or Cmaj/G, etc.)

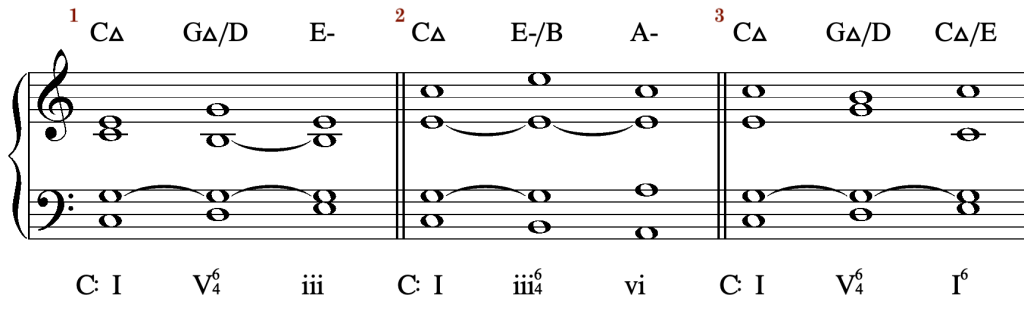

The example below gives us three common uses of the second inversion “Six-Four Chord” triad in context:

- Passing Chord (upward): Here we move smoothly between a root position Tonic (scale degree

) and root position Mediant (scale degree

) and root position Mediant (scale degree  ) using the “Six-Four” chord on the Dominant (scale degree

) using the “Six-Four” chord on the Dominant (scale degree  ) as a passing chord, smoothing out the voice leading and providing some variety. Note the upward stepwise motion in the bass voice, going into and out of the second inversion triad.

) as a passing chord, smoothing out the voice leading and providing some variety. Note the upward stepwise motion in the bass voice, going into and out of the second inversion triad. - Passing Chord (downward): Here we move smoothly between a root position Tonic (scale degree

) and root position SubMediant (scale degree

) and root position SubMediant (scale degree  ) using the “Six-Four” chord on the Mediant (scale degree

) using the “Six-Four” chord on the Mediant (scale degree  ) as a passing chord, smoothing out the voice leading and providing some variety. Note the downward stepwise motion in the bass voice, going into and out of the second inversion triad.

) as a passing chord, smoothing out the voice leading and providing some variety. Note the downward stepwise motion in the bass voice, going into and out of the second inversion triad. - Indirect Voice Exchange Here we have a change of voicing in the Tonic (scale degree

) chord, using the “Six-Four” chord on the Dominant (

) chord, using the “Six-Four” chord on the Dominant ( ) as a passing chord in between. The exchange of voices occurs between the alto and bass, exchanging chord tones E to C in soprano, and C to E in bass.

) as a passing chord in between. The exchange of voices occurs between the alto and bass, exchanging chord tones E to C in soprano, and C to E in bass.

Example 4. Examples of common second inversion “Six-Four” chord uses.

More on Doubling Chord Tones

We have learned that it is good practice to double the root in a four part SATB chorale style texture. The reason for this is to provide more strength to the identity of the chord by reinforcing the root with a second instance, and to provide more resonance. As a general rule, it will continue to be good practice to double the root of any triad in a four voice texture such as SATB. However, with the addition of inverted chords, we add not only more flexibility but a greater possibility for voice leading problems to arise such as parallel voice motion by perfect intervals (octaves and fifths) and spacing problems such as moving to a too wide distance between voices or crossing the voices. In these cases, where other sensible options are not possible when doubling the root, it is permissible to double one of the other two chord tones: the third and the fifth. When one has gained a better sense of control and command over the material, one might make different chord tone doubling choices for more musical reasons such as the development of a better melody or some other aesthetic choice provided no other problems are created.

We can summarize chord tone doubling now as follows:

- Always try to double the root whenever possible, regardless of the triad’s voicing position (root position, first or second inversions).

- First Inversion: When doubling the root is not ideal, you may double the fifth. Try, unless all other options are not possible, to avoid doubling the third. The reason for this is that the doubled third, also being the tone in the bass, will greatly obscure the function and identity of the chord which is, in most cases, not desirable.

- Second Inversion: When doubling the root is not idea, you may double the third. Doubling the fifth should be avoided at almost any cost as it will destabilize the identity of the chord.

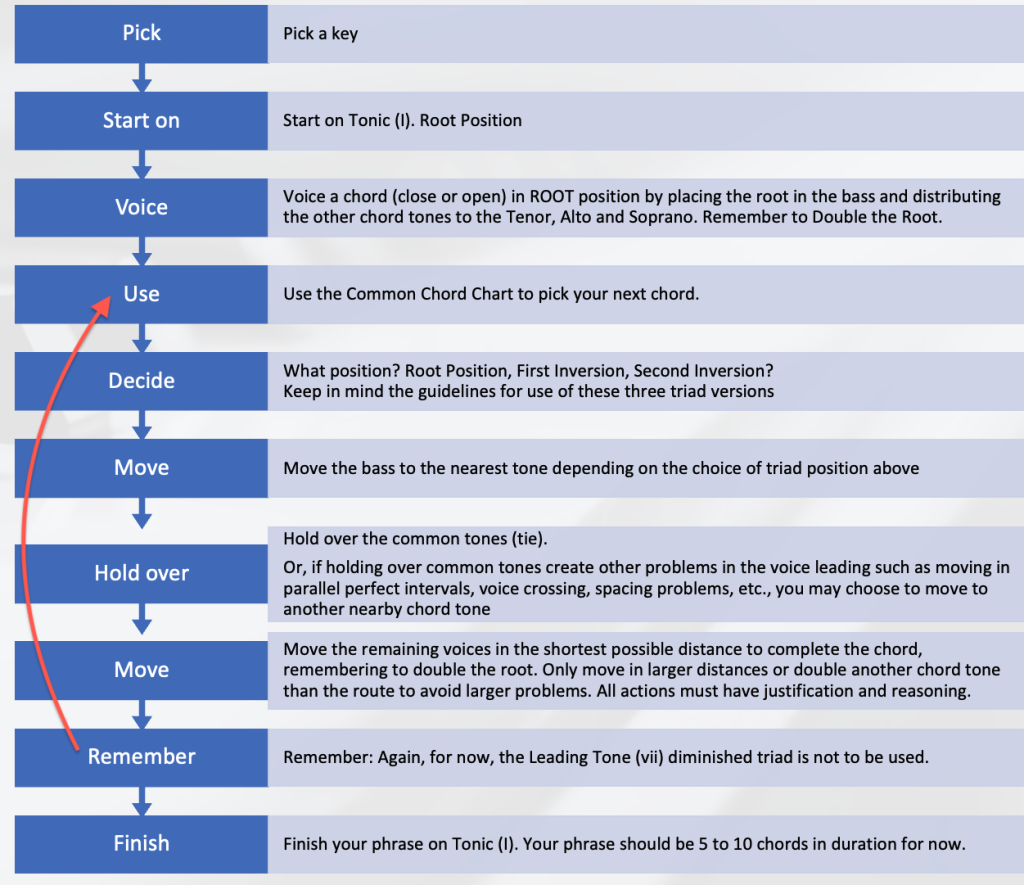

Chord Connection Guidelines: V2

The process of moving from one chord to another in short tonal phrases may be expanded now to include the triad inversions. The flowchart has been updated below:

Common Tone Chord Chart (Major Mode)

| Chord | Has common tones with... | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | iii | IV | V | vi |

| ii | IV | V | vi | (vii) |

| iii | I | V | vi | (vii) |

| IV | I | ii | vi | (vii) |

| V | I | ii | iii | (vii) |

| vi | I | ii | iii | IV |

| (vii) | ii | iii | IV | V |

EXAMPLES

Phrases in C Major, G Major, and F Major using a mixture of Root, 1st and 2nd Inversion Triads

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

RWU EXERCISES

Mixed Triads in the Major Mode

Using the template below, do the following:

- Realize the given harmonic progression (the Roman numeral analysis is provided).

- Compose three harmonic progressions of your choice, one may be in C Major, and the other two any major key of your choosing.

- Follow the guidelines set above. You must have at least one instance of a first inversion (“Six” chord) and one instance of a second inversion (“Six-Four” chord) triad in each of your phrases, properly handled and voice led.

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

- This chapter will be added shortly. This material was also covered in Roger Williams University's course Basic Musicianship (MUSIC 110) ↵

A triadic (or tertian) harmony with the third in the bass.

A three-note chord whose pitch classes can be arranged as thirds.

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a third (major or minor) above the root.

A pitch that belongs to a chord. Example: a c major triad has three chord tones, pitch-classes C, E, and G.

The lowest voice in SATB style, written in the bass clef staff with a down-stem; its generally accepted range is E₂–C₄

Arabic numerals and symbols that indicate the intervals above a bass note to be realized into chords and non-chord tones by performers. Used also for identification of chords in Roman numeral harmonic analysis

A type of jazz/pop score that typically notates only the melody and the chord symbols (written above the staff).

A group of pitches that are octave equivalent and enharmonically equivalent.

Ordering the notes of a chord so that it is entirely stacked in thirds. The root of the chord is on the bottom.

a single component frequency within a tone's harmonic series. Also referred to as a "partial".

A contrapuntal technique or musical passage where voices in two parts exchange notes between them.

Example:

Voice 1: a b

Voice 2: b a

A pitch (pitch class) in tertian harmony located the distance of a fifth (perfect, augmented, or diminished) above the root.

A melodic and harmonic goal. In classical tonal music, cadence types include Perfect Authentic (PAC), Imperfect Authentic (IAC), and Half (HC).

scale degree five (5) in a major/minor key in tonal music. Has a dominant area function.

When a given harmony’s influence lasts longer than a single chord. Usually this is accomplished by alternating the prolonged chord with other, less important chords.

When the bass note of a harmony is not the root of the chord. For example, when the third of the chord is in the bass instead of the root.

A four part musical texture with soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B) parts, abstracted through voice.

The density of and interaction between voices in a work

The lowest note of a triad or seventh chord when the chord is stacked in thirds.

A series of notes whose frequencies are multiples of the first frequency: 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5, etc. Starting with the pitch C₂, this would result in the series of pitches C₂, C₃, G₃, C₄, E₄, G₄, B♭₄, C₅, etc.

vibrations that travel through the air, or another medium, and can be perceived (heard) when they reach a person's or an animal's ear

appearing or occurring at intervals. In sound, this refers to the regular and predictable period (time to complete one full cycle with a crest and valley) of a stable sound wave.

An acoustic wave (energy vibration) that is perceived as sound

the state of being or process of becoming aware of something through the senses

A discrete tone with an individual frequency.

the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or tone. Also known as tone color or tone quality.

The physical science of sound.

As an acoustic phenomenon, frequencies vibrating at whole-number ratios with one another; as a cultural phenomenon, perceived stability in a chord or interval.

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord.

A term that summarizes the quality of the third, fifth, and seventh (if applicable) above the root of the chord. Common chord qualities are major, minor, diminished, half-diminished, dominant, and augmented.

the scientific study of sound perception and audiology. This includes speech, music, and other sound frequencies that travel through our ears.

a statement or proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true

the lowest frequency of a periodic waveform. In music, the fundamental is the musical pitch of a note that is perceived as the lowest partial present.

a complex effect which quantifies the subjective perception of rapid (15-300 Hz) amplitude modulation of a sound often in relation to one another.

Duplicating some notes of a chord in multiple parts.

A triadic (or tertian) harmony with the fifth in the bass

A way of labeling chords according the the scale degree upon which the chord is built in tonal music. The scale degree number is represented as a Roman numeral as opposed to an Arabic numeral and the case of the Roman numeral is often used to denote the quality of the chord with Upper Case as major and Lower Case as minor.

The relative position of a note within a diatonic scale. Indicated with a number, 1–7, that indicates this position relative to the tonic of that scale.

In tonality, the tonic (tonal center) is the tone of complete relaxation and stability, the target toward which other tones lead and to which all other tones in the mode/scale relate. The tonal center is defined as scale degree 1.