POSTLUDE: Fundamentals of Music (Review – From “Open Music Theory”)

21 Reading Clefs

Chelsey Hamm

Key Takeaways

In Western musical notation, pitches are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G these letter names repeat in a loop: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. This loop of letter names exists because musicians and music theorists today accept what is called octave equivalence, or the assumption that pitches separated by an octave should have the same letter name. More information about this concept can be found in the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff.

This assumption varies with milieu. For example, some ancient Greek music theorists did not accept octave equivalence. These theorists used more than seven letters of the Greek alphabet to name pitches.

Clefs and Ranges

The Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines chapter introduced four clefs: treble, bass, alto, and tenor. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. In the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff, we will see that having multiple clefs makes reading different ranges easier. The treble clef is typically used for higher voices and instruments, such as a flute, violin, trumpet, or soprano voice. The bass clef is usually utilized for lower voices and instruments, such as a bassoon, cello, trombone, or bass voice. The alto clef is primarily used for the viola, a mid-ranged instrument, while the tenor clef is sometimes employed in cello, bassoon, and trombone music (although the principal clef used for these instruments is the bass clef).

Each clef indicates how the lines and spaces of the staff correspond to pitch. Memorizing the patterns for each clef will help you read music written for different voices and instruments.

Reading Treble Clef

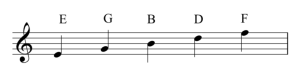

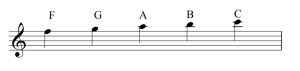

The treble clef is one of the most commonly used clefs today. Example 1 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a treble clef is employed. One mnemonic device that may help you remember this order of letter names is “Every Good Bird Does Fly” (E, G, B, D, F). As seen in Example 1, the treble clef wraps around the G line (the second line from the bottom). For this reason, it is sometimes called the “G clef.”

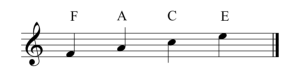

Example 2 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a treble clef. Remembering that these letter names spell the word “face” may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Bass Clef

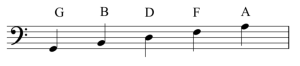

The other most commonly used clef today is the bass clef. Example 3 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a bass clef is employed. A mnemonic device for this order of letter names is “Good Bikes Don’t Fall Apart” (G, B, D, F, A). The bass clef is sometimes called the “F clef”; as seen in Example 3, the dot of the bass clef begins on the F line (the second line from the top).

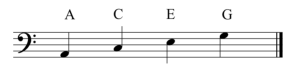

Example 4 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a bass clef. The mnemonic device “All Cows Eat Grass” (A, C, E, G) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Alto Clef

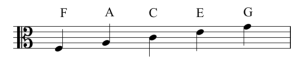

Example 5 shows the letter names used for the lines of the staff with the alto clef, which is less commonly used today. The mnemonic device “Fat Alley Cats Eat Garbage” (F, A, C, E, G) may help you remember this order of letter names. As seen in Example 5, the center of the alto clef is indented around the C line (the middle line). For this reason it is sometimes called a “C clef.”

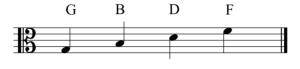

Example 6 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with an alto clef, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Grand Boats Drift Flamboyantly” (G, B, D, F).

Reading Tenor Clef

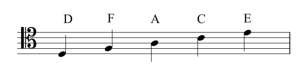

The tenor clef, another less commonly used clef, is also sometimes called a “C clef,” but the center of the clef is indented around the second line from the top. Example 7 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a tenor clef is employed, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Dodges, Fords, and Chevrolets Everywhere” (D, F, A, C, E):

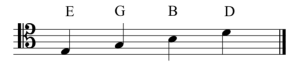

Example 8 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a tenor clef. The mnemonic device “Elvis’s Guitar Broke Down” (E, G, B, D) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Ledger Lines

When notes are too high or low to be written on a staff, small lines are drawn to extend the staff. You may recall from the previous chapter that these extra lines are called ledger lines. Ledger lines can be used to extend a staff with any clef. Example 9 shows ledger lines above a staff with a treble clef:

Notice that each space and line above the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing upwards. The same is true for ledger lines below a staff, as shown in Example 10:

Notice that each space and line below the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing downwards.

- The Staff, Clefs, and Ledger Lines (musictheory.net)

- Flashcards for Treble, Bass, Alto, and Tenor Clefs (Richman Music School)

- Printable Treble Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 3 to 5)

- Printable Bass Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 1 to 3)

- Printable Alto Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Printable Tenor Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Paced Game: Treble Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Bass Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Alto Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Tenor Clef (Tone Savvy)

Easy

Medium

- Worksheets in Treble Clef (.pdf)

- Treble Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Bass Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bass Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Alto Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Worksheets in Tenor Clef (.pdf)

Advanced

- All Clefs (.pdf)

- Writing and Identifying Notes Assignment #1 (.pdf, .mscx)

- Writing and Identifying Notes Assignment #2 (.pdf, .mscx)

Core sections comprise the main musical and poetic content of a song. Core sections include strophe (AABA and strophic form only), bridge, verse, chorus, prechorus, and postchorus.

A single step within a scale; usually indicated by either a solfège syllable or an Arabic numeral with a caret.

[["Chord","Has common tones with...","#colspan#","#colspan#","#colspan#","#colspan#","#colspan#","#colspan#","#colspan#"],["i","III","III+([latex]\\uparrow\\hat7[/latex])","iv","IV ([latex]\\uparrow\\hat6[/latex])","v","V ([latex]\\uparrow\\hat7[/latex])","VI","vi\uea97 ([latex]\\uparrow\\hat6[/latex])"],["ii\uea97","iv","","v","I ([latex]\\uparrow\\hat6[/latex])","VI","","VII","vii\uea97 ([latex]\\uparrow\\hat7[/latex])"],["ii","","","","","","","",""],["iii ","I","","V","","vi","","","vii\uea97"],["III+","","","","","","","",""],["iv","I","","ii","","vi","","","vii\uea97"],["IV","","","","","","","",""],["v","I","","ii","","iii","","","vii\uea97"],["V","","","","","","","",""],["VI ","I","","ii","","iii","","","IV"],["vi\uea97","","","","","","","",""],["VII ","ii","","iii","","IV","","","V"],["vii\uea97","","","","","","","",""]]

Key Takeaways

- A major scale is an ordered collection of half and whole steps with the ascending succession W‑W‑H‑W‑W‑W‑H.

- Major scales are named for their first note (which is also their last note), including any accidental that applies to the note.

- Scale degrees are solmization syllables notated by Arabic numerals with carets above them. The scale degrees are [latex]\hat1-\hat2-\hat3-\hat4-\hat5-\hat6-\hat7[/latex].

- Solfège solmization syllables are another method of naming notes in a major scale. The syllables are do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, and ti.

- Each note of a major scale is also named with scale-degree names: tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant, and leading tone.

- A key signature, consisting of either sharps or flats, appears at the beginning of a composition, after a clef but before a time signature.

- The order of sharps in key signatures is F, C, G, D, A, E, B, while the order of flats is the opposite: B, E, A, D, G, C, F. In sharp key signatures, the last sharp is a half step below the tonic (the first note of a scale). In flat key signatures, the second-to-last flat is the tonic.

- The circle of fifths is a convenient visual for remembering major key signatures. All of the major key signatures are placed on a circle in order of number of accidentals.

A scale is an ordered collection of half and whole steps (see Half and Whole Steps and Accidentals to review).

Major Scales

A major scale is an ordered collection of half- (abbreviated H) and whole steps (abbreviated W) in the following ascending succession: W-W-H-W-W-W-H. Listen to Example 1 to hear an ascending major scale. Each whole step is labeled with a square bracket and “W,” and each half step is labeled with an angled bracket and “H.”

Example 1. An ascending major scale.

A major scale always starts and ends on notes of the same letter name, one octave apart, and this starting and ending note determines the name of the scale. Therefore, Example 1 depicts a C major scale because its first and last note is a C.

The name of a scale includes any accidental that applies to the first and last note. Example 2 shows a B♭ (B-flat) major scale—not a B major scale, which would use a different collection of pitches. Note that the pattern of half and whole steps is the same in every major scale, as shown in Example 1 and Example 2.

Example 2. A B-flat major scale.

Scale Degrees, Solfège, and Scale-Degree Names

Musicians name the notes of major scales in several different ways. Scale degrees are solmization syllables notated by Arabic numerals with carets above them. The first note of a scale is [latex]\hat{1}[/latex] and the numbers ascend until the last note of a scale, which is also [latex]\hat{1}[/latex] (although some instructors prefer [latex]\hat{8}[/latex]). Example 3 shows a D major scale with each scale degree labeled with an Arabic numeral and a caret.

Example 3. A D major scale.

Below the scale degrees, Example 3 also shows another method of naming notes in a major scale: solfège solmization syllables. Solfège (a system of solmization syllables) are another method of naming notes in a major scale. The syllables do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, and ti can be applied to the first seven notes of any major scale; these are analogous to the scale degrees [latex]\hat{1}[/latex], [latex]\hat{2}[/latex], [latex]\hat{3}[/latex], [latex]\hat{4}[/latex], [latex]\hat{5}[/latex], [latex]\hat{6}[/latex], and [latex]\hat{7}[/latex]. The last note is do ([latex]\hat{1}[/latex]) because it is a repetition of the first note. Because do ([latex]\hat{1}[/latex]) changes depending on what the first note of a major scale is, this method of solfège is called movable do. This is in contrast to a fixed do solmization system, in which do ([latex]\hat{1}[/latex]) is always the pitch class C.

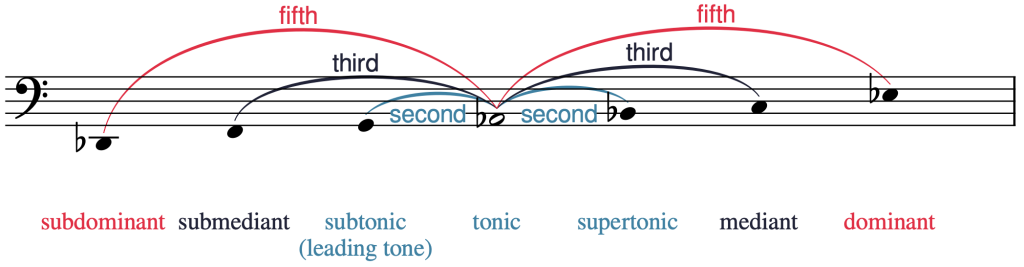

Each note of a major scale is also named with scale-degree names: tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant, leading tone, and then tonic again. Example 4 shows how these names align with the scale-degree number and solfège systems described above.

[table “37” not found /]

Example 4. Scale-degree numbers, solfège syllables, and scale-degree names.

Example 5 shows these scale-degree names applied to an A♭ major scale:

Example 5. An A♭ major scale with scale-degree names.

Example 6 shows the notes and scale-degree names of the A♭ major scale in an order that shows how the names of the scale degrees were derived. The curved lines above the staff show the intervallic distance between each scale degree and the tonic.

- The word dominant is inherited from medieval music theory, and refers to the importance of the fifth above the tonic in diatonic music.

- The word mediant means "middle," and refers to the fact that the mediant is in the middle of the tonic and dominant pitches.

- The Latin prefix super means “above,” so the supertonic is a second above the tonic. This is the only "super-" interval.

- The Latin prefix sub means “below”; the subtonic, submediant, and subdominant are the inverted versions (i.e., below the tonic) of the supertonic, mediant, and dominant respectively. (Note that in this text, we prefer the term leading tone instead of "subtonic" when referring to the scale-degree that is a half step below tonic, so named because it is often thought of as “leading” toward the tonic.)

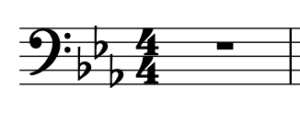

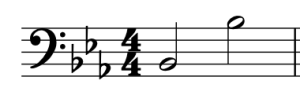

Key Signatures

A key signature, consisting of either sharps or flats, appears at the beginning of a composition, after a clef but before a time signature. You can remember this order because it is alphabetical: clef, key, time. Example 7 shows a key signature in between a bass clef and a time signature.

Key signatures collect the accidentals in a scale and place them at the beginning of a composition so that it is easier to keep track of which notes have accidentals applied to them. In Example 7, there are flats on the lines and spaces that indicate the notes B, E, and A (reading left to right). Therefore, every B, E, and A in a composition with this key signature will be flat, regardless of octave. In Example 8 both of these Bs will be flat because B♭ is in the key signature.

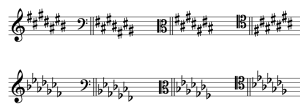

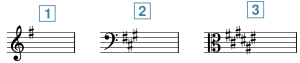

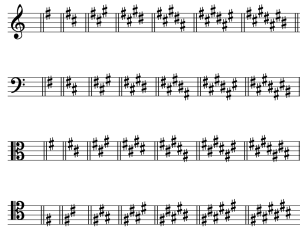

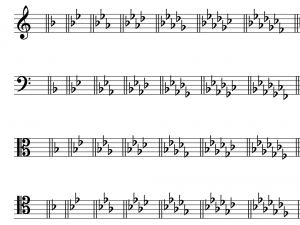

Flat key signatures have a specific order in which flats are added, and the same is true of the sharps in sharp key signatures. These orders apply regardless of clef. Example 9 shows the order of sharps and flats in all four clefs that we have learned:

The order of sharps is always F, C, G, D, A, E, B. This can be remembered with the mnemonic "Fat Cats Go Down Alleys (to) Eat Birds." The sharps form a zig-zag pattern, alternating going down and up. In the treble, bass, and alto clefs, this pattern "breaks" after D♯ and then resumes. In the tenor clef, there is no break, but F♯ and G♯ appear in the lower octave instead of the upper octave.

The order of the flats is the opposite of the order of the sharps: B, E, A, D, G, C, F. This makes the order of flats and sharps palindromes. The order of flats can be remembered with this mnemonic: "Birds Eat And Dive Going Copiously Far." The flats always make a perfect zig-zag pattern, alternating going up and down, regardless of clef, as seen in Example 9.

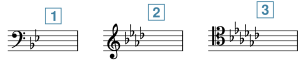

There are easy ways to remember which key signature belongs to which major scale. In sharp key signatures, the last sharp is a half step below the tonic (the first note of a scale). Example 10 shows three sharp key signatures in different clefs. Here's how to identify each with this method:

- The last sharp (in this case the only sharp), F♯, is a half step below the note G. Therefore, this is the key signature of G major.

- The last sharp, G♯, is a half step below the note A. Therefore, this is the key signature of A major.

- The last sharp, E♯, is a half step below the note F♯. Therefore, this is the key signature of F♯ major.

In flat key signatures, the second-to-last flat is the tonic (the first note of a scale). Example 11 shows three flat key signatures in different clefs. Here's how to identify each with this method:

- The second-to-last flat in this key signature is B♭. Therefore, this is the key signature of B♭ major.

- The second-to-last flat is A♭. Therefore, this is the key signature of A♭ major.

- The second-to-last flat is G♭. Therefore, this is the key signature of G♭ major.

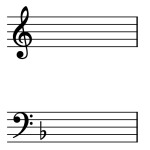

There are two key signatures that have no "tricks" that you will simply have to memorize. These are C major, which has nothing in its key signature (no sharps or flats), and F major, which has one flat: B♭ (Example 12).

Example 13 shows the key signature for C major (no sharps or flats) followed by all of the sharp key signatures in order in all four clefs: G, D, A, E, B, F♯, and C♯ major.

Example 13. The key signatures of C, G, D, A, E, B, F♯, and C♯ in all four clefs.

Example 14 first shows the key signature for C major (no sharps or flats), then all of the flat key signatures in order in all four clefs: F, B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, and C♭ major.

Example 14 first shows the key signature of C major (with no sharps or flats), and then the key signatures of F, B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, and C♭ in all four clefs.

There is one other "trick" that might make memorization of the key signatures easier: C major is the key signature with no sharps or flats, C♭ major is the key signature with every note flat (7 flats total), and C♯ major is the key signature with every note sharp (7 sharps total).

Major keys are said to be "real" if they correspond to one of the key signatures in Examples 13 or 14. If a double sharp or double flat would be needed for a key signature, then that key signature would be "imaginary." Occasionally, you may encounter music in an imaginary key. Example 15 shows an F♭ major scale; an F♭ major key signature is imaginary because it would need a B𝄫.

Example 15. An F♭ major scale in treble clef.

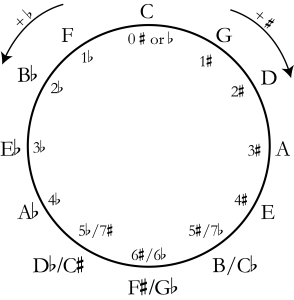

The Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is a convenient visual. In the circle of fifths, all of the major key signatures are placed on a circle in order of number of accidentals. The circle of fifths is so named because each key signature is a fifth away from the ones on either side of it. Example 16 shows the circle of fifths for major key signatures:

If you start at the top of the circle (12 o'clock), the key signature of C major appears, which has no sharps or flats. If you continue clockwise, sharp key signatures appear, each subsequent key signature adding one more sharp. If you continue counter-clockwise from C major, flat key signatures appear, each subsequent key signature adding one more flat. The bottom three key signatures (at 7, 6, and 5 o'clock) in Example 16 are enharmonically equivalent. For example, the B major and C♭ major scales have different key signatures—five sharps and seven flats, respectively—but they sound the same because the notes B and C♭ are enharmonically equivalent.

- Major Scales Tutorial (musictheory.net)

- Major Scales (Practical Chords and Harmonies)

- Major Scales (YouTube)

- Scale Degree Names (musictheoryfundamentals.com)

- Scale Degree Names (musictheory.net)

- Solfège History and Tutorial (Earlham College)

- Scale Degrees, Solfège, and Scale-degree Names (YouTube)

- Major Key Signatures (musictheory.net)

- Sharp Key Signatures (YouTube)

- Flat Key Signatures (YouTube)

- Major Key Signature Flashcards (music-theory-practice.com)

- The Circle of Fifths (YouTube)

- The Circle of Fifths (Classic FM)

A core section of a popular song that is lyric-invariant and contains the primary lyrical material of the song. Chorus function is also typified by heightened musical intensity relative to the verse. Chorus sections are distinct from refrains, which are contained within a section.

Notes whose exact pitch sounds somewhere between the flat and regular versions of a scale degree, particularly 3̂ and 7̂.

Sections that are lyric-variant and often contain lyrics that advance the narrative.

Sections that are lyric-variant and often contain lyrics that advance the narrative.

One-twelfth of an octave; generally considered to be the smallest interval in Western musical notation.

The process by which a non-tonic triad is made to sound like a temporary tonic. It involves the use of secondary dominant or leading-tone chords.