POSTLUDE: Fundamentals of Music (Review – From “Open Music Theory”)

37 Roman Numerals and SATB Chord Construction

Samuel Brady and Kris Shaffer

Key Takeaways

- Roman numeral analysis is an analytical procedure in which musicians use Roman numerals to identify chords within the context of key signatures.

- Roman numerals identify the scale degree of the chord’s root, the chord’s quality, and any extensions or inversions the chord may include.

- Uppercase Roman numerals denote major triads, and lowercase Roman numerals denote minor triads. A o symbol after a lowercase Roman numeral represents a diminished triad, while a + sign after an uppercase Roman numeral represents an augmented triad.

- The Roman numeral quality of a seventh chord is dependent on the chord’s triad; the exceptions are half-diminished and fully diminished seventh chords, whose qualities are dependent on their chordal seventh.

- When constructing a chord in SATB style, there are six rules to keep in mind: stem direction, chord construction, range, spacing, voice crossing, and doubling.

Writing Roman Numerals

Music theorists use Roman numerals to identify chords within the context of key signatures. Roman numerals identify the scale degree of the chord’s root, the chord’s quality, and any extensions or inversions the chord may include. Because Roman numerals convey the same information across major and minor key signatures, using them can save time in analyzing Western common practice music.

The three columns of Example 1 show the Arabic numerals 1 through 7 alongside the corresponding uppercase and lowercase Roman numerals.

[table “68” not found /]

Example 1. Arabic and Roman numerals.

To type uppercase Roman numerals, use the uppercase Latin alphabet letters “I” and “V”; likewise, for lowercase Roman numerals, type the lowercase “i” and “v.” The Roman numerals IV (4) and VI (6) are often confused; to remember the difference, think of IV (4) as V minus I (5 minus 1), and VI (6) as V plus I (5 plus 1).

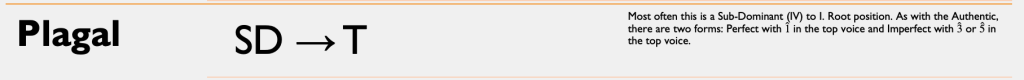

Handwritten uppercase Roman numerals have horizontal bars across the top and bottom of the numeral, in order to further distinguish between uppercase and lowercase (Example 2). There is no such difference with lowercase Roman numerals.

Roman Numerals and Triad Quality

Roman numerals indicate three things: the scale degree of a chord’s root, the quality of the chord, and the chord’s inversion (see Inversion below). The number represented by the Roman numeral (see Example 1) corresponds to the scale degree of the chord’s root in whatever key the music is in. Uppercase Roman numerals denote major triads, and lowercase Roman numerals denote minor triads. For example, in a major key, a chord built on the first scale degree, ![]() or do, is identified as “I,” and a chord built on the second scale degree,

or do, is identified as “I,” and a chord built on the second scale degree, ![]() or re, is identified by the lowercase Roman numeral “ii.” Lowercase Roman numerals followed by a superscript “o” (such as viio) represent diminished triads. Uppercase Roman numerals followed by a + sign (for example, the rare V+) represent augmented triads.

or re, is identified by the lowercase Roman numeral “ii.” Lowercase Roman numerals followed by a superscript “o” (such as viio) represent diminished triads. Uppercase Roman numerals followed by a + sign (for example, the rare V+) represent augmented triads.

In the analysis of Western music, Roman numerals are generally placed below the bottom staff. Some music theorists prefer to use only uppercase Roman numerals, a system which assumes chord quality is intuited; in this textbook, we privilege the distinction of triadic qualities as denoted by uppercase and lowercase Roman numerals.

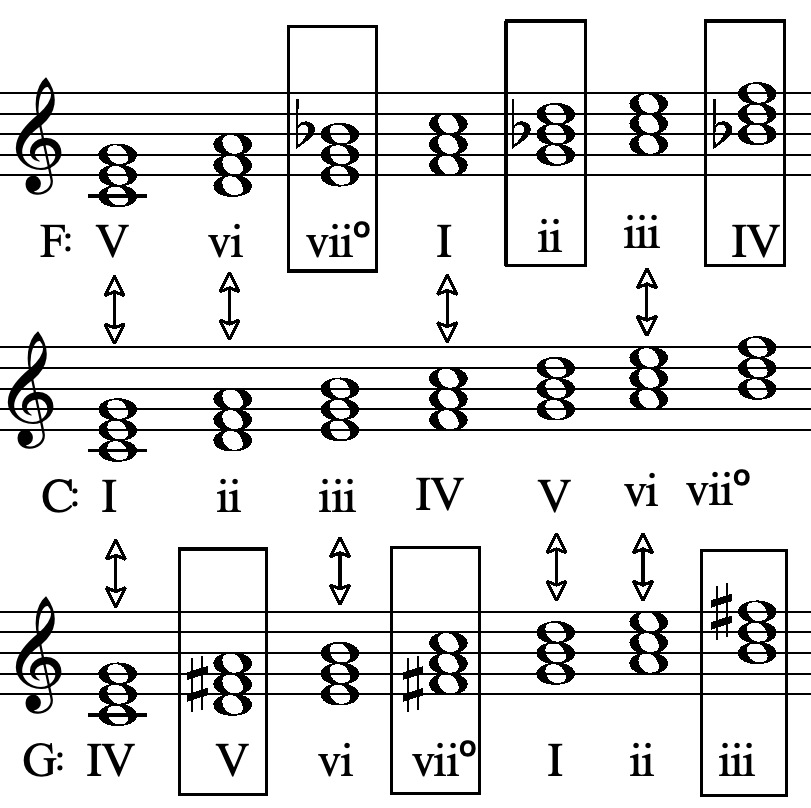

Example 3 shows the triads and seventh chords of a G major scale, labeled with chord symbols and now Roman numerals (in blue). The solfège and scale degree of the roots are also labeled.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8514239/embed

Example 3. Roman numerals of triads in major and minor keys.

The Roman numerals and qualities of triads in major keys are as follows:

- I: major

- ii: minor

- ⅲ: minor

- IV: major

- V: major

- vi: minor

- vii°: diminished

The Roman numerals and qualities of triads in minor keys are as follows:

-

- ⅰ: minor

- ii°: diminished

- III: major

- iv: minor

- v: minor

- V: major (raised leading tone)

- VI: major

- VII: major

- vii°: diminished (raised leading tone)

Note that the quality of v/V and VII/viio differs depending on whether or not the leading tone is raised.

Roman Numerals and Seventh Chord Quality

Roman numeral labels for seventh chords add a superscript 7: for example, V7, ii7, and viio7. The capitalization of the Roman numeral depends on the quality of its triad: uppercase for a major triad (e.g., V7), lowercase for a minor or diminished triad (e.g., ii7). Half-diminished and fully diminished seventh chords, which both contain a diminished triad, are distinguished by an additional symbol after the lowercase Roman numeral: ∅ for half-diminished (e.g., vii∅7) and o for fully diminished (e.g., viio7).

Example 4 shows the triads and seventh chords of a G minor scale labeled with chord symbols and now Roman numerals (in blue). The solfège and scale degree of the roots are also labeled.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8514287/embed

Example 4. Roman numerals of seventh chords in major and minor keys.

The Roman numeral and qualities of seventh chords in major keys are as follows:

-

- I7: major-major seventh (major seventh)

- ii7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- ⅲ7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- IV7: major-major seventh (major seventh)

- V7: major-minor seventh (dominant seventh)

- vi7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- vii∅7: half-diminished seventh

The Roman numeral and qualities of seventh chords in minor keys are as follows:

-

- ⅰ7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- ii∅7: half-diminished seventh

- III7: major-major seventh (major seventh)

- iv7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- v7: minor-minor seventh (minor seventh)

- V7: major-minor seventh (dominant seventh)

- VI7: major-major seventh (major seventh)

- VII7: major-minor seventh (dominant seventh)

- vii°7: fully diminished seventh (diminished seventh)

Note that the quality of v7/V7 and VII7/viio7 differs depending on whether or not the leading tone is raised.

Additionally, major seventh and dominant seventh chords have the same Roman numeral nomenclature; in other words, a I7 chord and a V7 chord are written the same even though the former is a major seventh chord and the latter is a dominant seventh chord. The difference would be discerned from the musical context.

Inversion

Roman numerals also denote inversions, shown through figured bass symbols placed after the Roman numeral (see the Inversion and Figured Bass chapter). For example, a superscript 6 represents a first inversion triad, and the figures ![]() would indicate a second inversion seventh chord. Example 5 shows four different inverted chords with Roman numerals:

would indicate a second inversion seventh chord. Example 5 shows four different inverted chords with Roman numerals:

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6869635/embed

Example 5. Four inverted chords with Roman numerals and figures.

Roman Numeral Analysis

To complete a Roman numeral analysis, begin by identifying the work’s key and writing it under the key signature at the beginning of the work, using an uppercase letter name for a major key and a lowercase letter name for a minor key. It can also be helpful to write a lowercase “m” following the letter name of a minor key (e.g., “dm” for D minor). Be sure to apply any applicable accidental (e.g., “E♭” for E-flat major).

After you identify and write the key at the start of the work, follow these steps for each chord to complete the Roman numeral analysis:

-

- If a chord is in inversion, stack it in root position (preferably mentally).

- Identify all the notes of the chord, taking its quality into account.

- Write the Roman numeral that corresponds with the scale degree of the chord’s root, reflecting the quality in the Roman numeral (uppercase or lowercase).

- Write any additional quality symbols ( o, ∅, +) as needed.

- Write figures after the Roman numeral.

Example 6 shows a Roman numeral analysis for Johann Sebastian Bach’s chorale “Jesu meiner Seelen Wonne” (1642), which translates to “Jesus, delight of my soul.” When analyzing this chorale, ignore the notes in parentheses. It is recommended that you cover up the Roman numerals in this example and try to generate them on your own before uncovering them:

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6867245/embed

Example 6. Roman numeral analysis of an excerpt of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Jesu, meiner Seelen Wonne” (BWV 359).

Roman numeral analysis is not just limited to chorales; indeed, you can apply them to many different genres of music. Example 7 shows an excerpt from “Caro Mio Ben” (c. 1783), which translates to “Dearly beloved” and is attributed to Guiseppe Giodani, with a Roman numeral analysis:

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6867246/embed

Example 7. Roman numeral analysis of an excerpt of Giuseppe Giordani’s “Caro Mio Ben.”

When the same chord occurs two or more times in a row, which is common, you can choose whether to repeat the Roman numeral (as in measure 1 of Example 7) or not (as in measure 2 of Example 6).

Writing Chords in SATB Style

Music theorists sometimes simplify compositions into four parts (or voices) in order to make their harmonic content more readily accessible. This practice is called SATB style, abbreviated after the four common voice parts of a choir––soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T), and bass (B). When constructing a chord in strict SATB style, there are six rules musicians generally follow:

- Stem Direction

- Chord Construction

- Range

- Spacing

- Voice Crossing

- Doubling

These six parameters form the basis of counterpoint and part writing, explored further in the sections Counterpoint and Galant Schemas and Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation.

Stem Direction

On a grand staff in SATB style, the soprano and alto are written in the treble clef (upper staff), while the tenor and bass are written in the bass clef (lower staff). The soprano and tenor voices receive up-stems, while the alto and bass parts receive down-stems. If the stem direction is crossed, this is an error. Example 8 shows a chord with incorrect stemming, followed by the corrected version.

Chord Construction

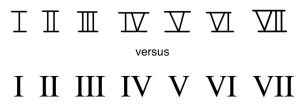

Be sure to check each chord for correct notes and accidentals, and make sure that your chords are not missing any notes. In Example 9, the first chord has accidentals erroneously added to two of the pitches, which are removed in the second chord to create a correct B diminished triad in first inversion.

The bass voice must always correspond with the inversion that the Roman numeral’s figures indicate. However, the order of the upper notes can be arranged in many ways. In other words, there is not necessarily just one correct way to voice a chord.

Range

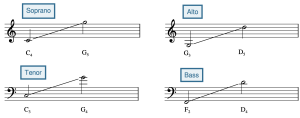

There is a generally accepted range for each voice (Example 10):

- Soprano – C4 to G5

- Alto – G3 to D5

- Tenor – C3 to G4

- Bass – F2 to D4

In Example 11, the soprano and bass notes are out of range; this is corrected by moving the soprano note down by an octave and the bass note up by an octave.

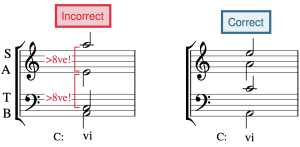

Spacing

There should be no more than an octave between adjacent upper voices (soprano and alto, alto and tenor) and no more than a twelfth between the tenor and bass. The most common spacing error occurs between the alto and tenor because the notes appear in different clefs. Example 12 first shows a chord with incorrect spacing—the soprano and alto are more than an octave apart, as are the alto and tenor—followed by a corrected version:

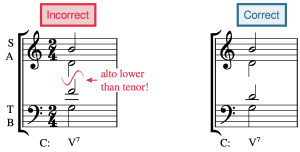

Voice Crossing

The ranges of voices should not cross. In other words, the soprano must always be higher than the alto, the alto must always be higher than the tenor, and the tenor must always be higher than the bass. In Example 13, the alto and tenor voices are crossed. This error is also the most common between the alto and tenor voices.

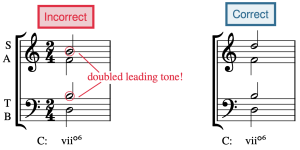

Doubling

In a triad, the note in the bass is usually doubled in an upper voice. However, there is an exception to this: the leading tone is never doubled. Other tendency tones, such as chordal sevenths, are also never doubled. Seventh chords don’t have any notes doubled because they contain four notes, one for each voice part. Incorrect doubling is seen in the first measure of Example 14, where the leading tone is doubled, followed by a corrected voicing in the second measure.

- Roman Numeral Analysis: Triads (musictheory.net)

- Harmonizing Scales & Roman Numeral Analysis (Kaitlan Bove)

- Roman Numerals (learnmusictheory.net)

- Roman Numeral Analysis (Phillip Magnuson)

- Roman Numeral Analysis (8notes.com)

- Roman Numeral Chord Symbols (Robert Hutchinson)

- Roman Numerals in Major Flashcards (gmajormusictheory.org)

- Roman Numerals in Minor Flashcards (gmajormusictheory.org)

- Inversion & Roman Numerals in Major Flashcards (gmajormusictheory.org)

- Inversion & Roman Numerals in Minor Flashcards (gmajormusictheory.org)

- How the Roman Numeral System Works (YouTube)

- Roman Numeral Identification, pp. 15–16, 18 (.pdf), pp. 5–7 (.pdf), pp. 1, 3, 4 (.pdf), (.pdf, .pdf, .pdf, .pdf)

- Roman Numeral Identification and Construction, p. 14 (triads) and 17 (seventh chords) (.pdf), p. 11 (.pdf), p. 8 (.pdf), p. 5 (.pdf), (website, website)

- Roman Numeral Construction, p. 22 (.pdf)

Key Takeaways

- Identifying the Key: Discerning the key of a music piece requires more than just the tonic triad or a repeated chord. It's essential to understand the underlying musical markers via the defining scale degrees as overlapping, common chords in closely related keys can create ambiguity.

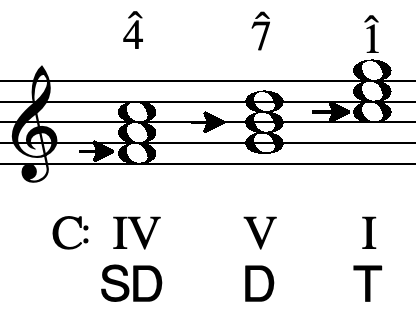

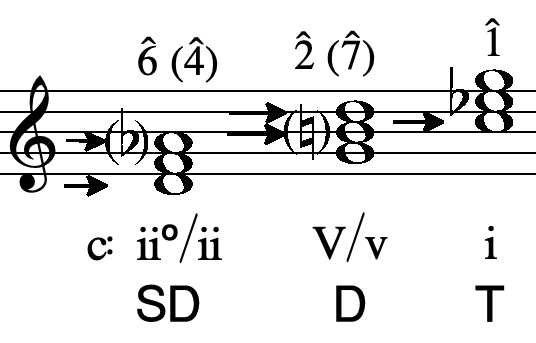

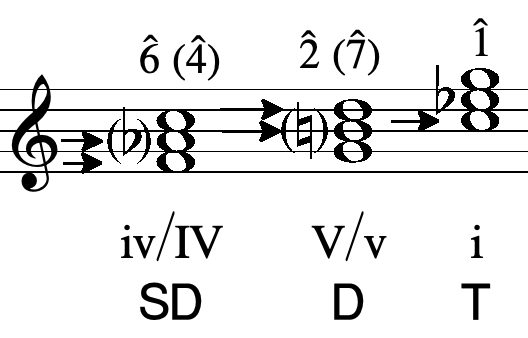

- Establishing the Tonal Center: The defining scale degrees in major are [latex](\hat4)[/latex] and [latex](\hat7)[/latex]. In minor, the key and mode is defined by scale degrees [latex](\hat2)[/latex], [latex](\hat4)[/latex], and [latex](\hat6)[/latex].

- Tritone Resolutions: Diatonic tritones in both major and minor modes exhibit specific melodic voice-leading tendencies.

- Role of Cadences: Cadences play a pivotal role in establishing the tonal center and the key by emphasizing the key and mode defining scale degrees, omitting neighboring keys from consideration.

- The Four Cadence Types: Authentic, Deceptive, Half, and Plagal.

- Guidelines for Better Progressions: Culminating general guidelines are provided in summary to help craft better progressions, emphasizing root progressions, chord usage, and voice leading.

Understanding Keys

How do we identify the key of a tonal music piece? Simply sounding the tonic triad or starting and concluding a musical phrase with an identical chord doesn't unequivocally confirm the key. To truly discern the key and establish a robust tonal center, our mind requires specific musical cues to form a contextual understanding. What are these auditory markers?

Consider the keys that are closely related, positioned adjacent to one another on the Circle of Fifths:

It's evident that many chords overlap among these keys. If our aim is to denote C major and we play chords common to G major, ambiguity arises between C and G major. Likewise, playing chords shared between C and F major introduces uncertainty about the key.

Establishing the Tonal Center

To differentiate and firmly set the key, one should play notes exclusive to the desired key, excluding the ones from adjacent keys on the Circle of Fifths. Investigation reveals that in the major mode, scale degrees [latex](\hat4)[/latex] and [latex](\hat7)[/latex] are pivotal for key determination. In minor mode, [latex](\hat4)[/latex] remains crucial, while the leadng-tone [latex](\hat7)[/latex] is derived from the Ascending form. The uniqueness of the minor mode is further reinforced by scale degrees [latex](\hat2)[/latex] and [latex](\hat6)[/latex]. Together, These degree pairs inherently demarcate the diatonic tritone, lending each mode its distinctive sound and attributes.

Cadences are essential here for helping us establish the tonal center and the key, as they not only conclude a harmonic sequence but also distinctly affirm the key by emphasizing the above-discussed defining scale degrees, thereby omitting neighboring keys from the tonal consideration.

Major Mode

In the major mode, the SubDominant and SuperTonic chords, sourced from the SubDominant region, encompass the defining scale degree [latex](\hat4)[/latex]. Meanwhile, chords from the Dominant region embed the leading-tone, scale degree [latex](\hat7)[/latex].

Both the Major-Minor (Dominant) Seventh chord and the Leading-Tone diminished triad encompass scale degrees [latex](\hat4)[/latex] and [latex](\hat7)[/latex]. These chords, by possessing both of the defining scale degrees, robustly fortify the tonal center in major mode.

Minor Mode

The mechanism in the minor mode parallels the major but offers more variety due to the dual nature of modern minor (i.e. the Ascending and Descending forms). Both the SubDominant and SuperTonic encompass key and mode-defining scale degrees [latex](\hat2)[/latex], [latex](\hat4)[/latex], and [latex](\hat6)[/latex]. It's noteworthy that either minor form, with a variable scale degree [latex](\hat6)[/latex]serve equally well in defining the key. In addition, when in the Ascending form, we get a leading-tone scale degree [latex](\hat7)[/latex], also providing a strong sense of definition.

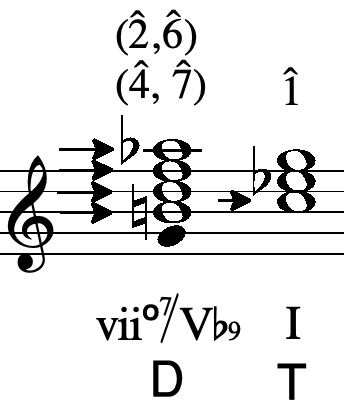

The fully diminished seventh chord, built on the raised scale degree [latex](\hat7)[/latex] from the Ascending (Harmonic) form of minor, and possessing the Natural sixth scale degree, is very potent, encapsulating all minor key and minor mode-defining scale degrees. This chord, akin to the diminished triad, can be thought of as an incomplete, rootless voicing of a ninth chord founded on the Dominant, essentially as a Dominant Seventh with an added flat ninth.

We will come back to the fully diminished seventh chord and explore its many additional possibilities in a later chapter.

Tritone and Scale Degree Melodic Tendencies

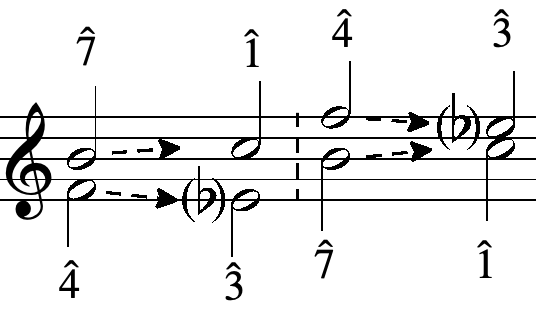

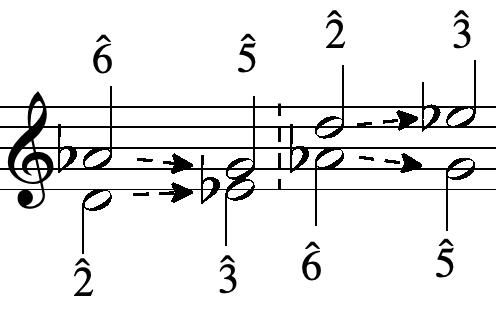

Earlier, we delved into the tendencies of the pivot tones in minor mode (tendency tones). Expanding on this concept, the diatonic tritones in both major and minor modes, demarcated by key and mode-defining degrees mentioned above, exhibit specific melodic voice-leading propensities. In both major and minor:

In Natural (Descending) minor:

The Four Cadence Types

There are four primary types of cadences (closes) in tonal music: Authentic, Deceptive, Half, and Plagal.

Authentic

The Authentic cadence is the most definitive cadence, affirming the key and concluding on the Tonic triad. There are two types: Perfect (top voice melody terminates on the Tonic) or Imperfect (top voice melody concludes on another scale degree).

With regard to SATB voice leading, the most conclusive version of the Authentic cadence has the following:

- Each chord of the Cadence in Root Position

- The Dominant chord must be a complete chord with the root sounding (i.e. not a diminished triad or fully diminished seventh).

- Seventh chords, except for the Tonic triad, may be used, provided the voice-leading allows.

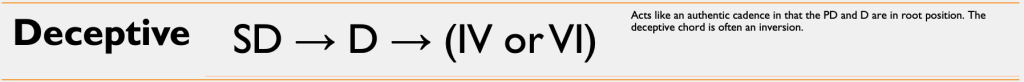

Deceptive

The Deceptive cadence seemingly sets up a closure but veers away from the Tonic chord, adding a twist to the listener's expectation. It is often a good way to both reaffirm a tonal center and key, but also provide further momentum in the musical phrase.

Half

The Half cadence offers a moment of pause, culminating on the Dominant chord rather than the Tonic, which then often moves on with a new musical phrase.

Plagal

Finally, we have the Plagal cadence, often termed the "Church" or "Amen" cadence. This cadence omits the Dominant, resulting in a less decisive closure. It is often used as an extension to an ending, after the sounding of an Authentic cadence, the purpose being to provide a more resolute conclusion. This cadence type appears regularly in popular song and contemporary pop, country and folk music.

As with the Authentic cadence, we have two forms of Plagal: Perfect and Imperfect, defined the same way as in the Authentic cadence by way of which scale degree is in the top melodic voice.

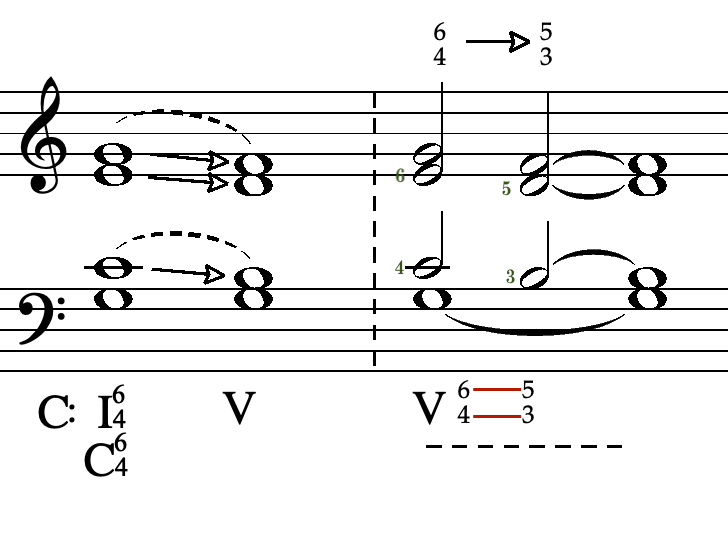

The Second Inversion (Six-Four) Triad in the Cadence

The Tonic second inversion triad, or the "Six-Four" chord, is pivotal in cadences. In the cadence. this chord is heard as a Dominant 6-4 dissonant suspension rather than a Tonic chord. How is this possible? The Dominant tone (scale degree [latex](\hat5)[/latex) is in the bass and, as we already know, any bass voice will exerts it's overtone series over the sounding notes above. Thus, the chord, by its very nature, is unstable, and it is quite easy and natural for the upper tones to have a strong pull toward neighboring tones that resolve in a root position chord (with the bass tone as the root), in essence, coming into "focus" and resonance with the harmonic series. This is one reason why we must be careful when using the second inversion triad, its inherent instability and its being at odds with the sounding tones.

We may use this Cadential 6/4 chord in any Authentic cadence, sounding immediately after any pre-Dominant (SubDominant) chord, before the sounding of the Dominant chord. The effect is powerful and creates, as mentioned above, a sense of prolonging and tension, further elevating the final resolution to the Tonic. While it might be used as part of a Deceptive cadence, due to its power and affect, it is not well suited to such a situation unless very strongly warranted by the musical context.

Guidelines for Better Progressions

Root Progressions (in Major and Minor)

- Ascending root progressions, which move a fourth upward or a third downward, can occur anytime. However, avoid repetitive usage.

- Descending progressions, moving a fourth downward or a third upward, should be used when they contribute to an overall upward motion.

- Adjacent progressions sparingly unless specified otherwise. They aren't prohibited.

Chord Usage (in Major and Minor)

Triads

- Triads in root position are versatile and may be used anytime.

- Sixth chords enrich voice leading, especially in outer voices, and prepare dissonances. They may be used anytime (except at the start or end of a musical phrase).

- Use six-four chords cautiously. They're optimal in cadences (i.e. the Cadential 6/4) and with a moving bass-line in stepwise motion. Exercise care in all other situations.

- Diminished triads give a sense of necessity when introducing a chord, and further may be considered as a Dominant seventh chord.

Seventh Chords

- Seventh chords are as versatile as triads when prepared and resolved. They're best used where the seventh demands a specific resolution or treatment.

- Inversions of seventh chords improve voice leading.

The Minor Mode

- The careful handling of the pivot/tendency tones are essential. Incorporate the pivot tones during root progression harmonic progression outlines.

- Staying exclusively in one region (Ascending or Descending) can jeopardize the minor mode's character.

- Transitioning between regions should respect pivot tones (i.e. the four pivot tone guidelines).

- Triads may require inversions to prepare or resolve dissonances, especially with a pivot tone in bass.

- The same rules apply to seventh chords.

- After certain diminished triads, it's generally better to use the Ascending major Dominant chord (V).

- All diminished triads and their seventh chords have a distinct drive due to their dissonance.

- The augmented triad's versatility lets it transition between ascending and descending minor scales.

Voice Leading

- Avoid unmelodic intervals, especially without altered chords.

- Avoid repetitive tone progressions with the same harmony.

- Aim for a high and possibly a low point.

- Use steps and leaps for varied interval sequences, maintaining a mid-range.

- After a significant leap from the mid-range, try to return to it.

- If the mid-range is left stepwise, perhaps balance with an octave leap.

- If repetition is unavoidable, a direction change might help.

- These guidelines apply primarily to soprano and bass. If applied to middle voices, it elevates the overall smoothness. However, focusing on the outer voices is sufficient for now.

EXAMPLES: Triad Inversions and Seventh Chords in the Minor Mode

If the score above is not displaying properly you may CLICK HERE to open it in a new window.

RWU EXERCISES

Major and Minor: Chord Connection with Non-Common Chord Tones and Freer Treatment of Dissonance

Using the template below, please do the following:

- Compose at least four (4) harmonic progressions of your choice in SATB style, at least 7 to 12 chords in length:

- At least two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice) and two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

- Consider the general guidelines above when constructing your phrases

- Each phrase should be planned out with root progression and harmonic regions in mind.

- Each phrase should have a good mixture of seventh chords and triads.

- Each phrase should contain one Deceptive cadence somewhere within the phrase and end with an Authentic cadence (perfect or imperfect)

- Two of your phrases should end with an Authentic cadence which uses the Cadential Six-Four chord

- Label your cadences with the following text: DC (Deceptive Cadence), IAC (Imperfect Authentic Cadence), PAC (Perfect Authentic Cadence).

- At least two (2) in the Major Mode (different keys of your choice) and two (2) in the Minor Mode (different keys of your choice)

(you must be logged into your Noteflight account to open the activity templates above)

Schoenberg Theory of Harmony Examples

Further Reading

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Theory of Harmony

- Schoenberg, Arnold: Structural Functions of Harmony

A single step within a scale; usually indicated by either a solfège syllable or an Arabic numeral with a caret.

Perfect Unison