Modal Counterpoint

1 Introduction to Species Counterpoint

Key Takeaways

- Species counterpoint is a step-by-step method to learn how to write simple melodies and to combine them into a coherent musical phrase.

- This chapter recaps some key concepts covered in Basic Musicianship (which may be reviewed in the Fundamentals section) and introduces a few basic “rules” (read: guidelines) that will be relevant for each of the following chapters, including some terms for:

- Tonal Consonance and Dissonance:

- Perfect consonances: perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves

- Imperfect consonances: major and minor thirds and sixths

- Dissonances: all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals

- The Four Types of Two-Part Voice Motion:

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) as in similar motion but retain the exact same distance between them, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

- Tonal Consonance and Dissonance:

- The study of counterpoint is not designed to create “good” music but rather develop skills and reenforce basic musical concepts through active learning and creation, and serve as a foundation upon which to build further knowledge. Counterpoint exercises (and four-part tonal harmony exercises to come) are analogous to, say, lifting weights as part of athletic training or the study of calculus as part of the training in engineering. Thus, these exercises are not intended to produce anything close to finished songs or well-constructed compositions. However, and what is an important challenge, one should strive to make them as musical as possible within the limited guidelines and resources provided. While the “rules” involved are somewhat linked to music in the 16th century, the idea really is to hone skills, independent of any specific repertoire or musical style. For context, I’ve provided a few great musical examples from the modal period of the 16th century at the end of this section.

- At this time we will explore three of the five species of counterpoint: First (note against note in a 1:1 ratio), Second (two notes against one note in a 2:1 ratio), and Fourth Species (syncopated 1:1). The other species may be explored at a later time.

We begin our study of counterpoint with a specific method called species counterpoint. The term “species” is probably most familiar as a way of categorizing animals, but it is also used in a wider sense to refer to any system of grouping similar elements. Here, the species are types of exercises that are done in a particular order, introducing one or two new musical “problems” (or what we might call, challenges) at each stage.

While there are many variants on this approach, the chapters here are closely modeled on Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus, 1725). Many composers and songwriters from the 18th century to the present day have used this method, or some variation on it, while learning their craft. In the first part of Gradus ad Parnassum, Fux works through five species of counterpoint for combining two voices. In our study in music theory, we will focus only on the First, Second, and Fourth species of Counterpoint. Later study of counterpoint will involve the remaining species, Third and Fifth.

Before diving into each species, we will begin by introducing principles that apply to writing lines in any of the species. These principles build on concepts from the Fundamentals section, such as intervals and scale degrees.

For a review of the foundations of Diatonicism, please watch:

The Psychology of Music and the Effect of Counterpoint

Species counterpoint will not involve a specific style (classical, baroque, romantic, pop/rock, etc.). Instead, given exercises will set aside for the moment important musical elements like orchestration, melodic motives, formal structure, and even many elements of tonal harmony and rhythm, in order to focus very specifically on a small set of musical problems that demand solution. These problems are closely related to how some basic principles of auditory perception and cognition (i.e., how the brain perceives and conceptualizes sound) play out in musical structure.

For example, our brains tend to assume that sounds similar in pitch or timbre come from the same source. Our brains also listen for patterns, and when a new sound continues or completes a previously heard pattern, we typically assume that the new sound belongs together with those others. This is related to some of the most deep-seated parts of our human experience, and even has roots in our evolution. Hearing a regular pattern typically indicates a predictable environment that may encourage a sense of safety and imprint familiarity, while change can signal not only an unfamiliar experience but trigger a heightened attention to the source (and even, in a distant way, our “fight/flight” response). This system for directing attention (and adrenaline) where it is most likely to be needed has been essential to the survival of the human species. While listening to music in the 21st century does not typically require us to listen out for sources of danger (such as animal predators), some part of that evolutionary experience is “hard-wired” into the psychology of human listening, and it plays an important role in what gives music its emotional effect—even in a safe listening environment.

For many listeners, music that simply makes it easy for the brain to parse and process sound is often labeled as boring—it calls for no heightened attention, it doesn’t increase our heart rate, make the hair on the back of our neck stand up, or give us a little jolt of our favorite drug: dopamine. On the other hand, music that constantly activates our senses and thus triggers our innate sense of danger is usually not pleasant for most listeners. That being the case, often a balance between tension and relaxation, motion and rest, is fundamental to much of the music we will study.

The study of counterpoint helps us to engage several important musical “problems” in a very limited context, such that we may develop compositional and analytical skills that can then be applied widely to many aspects of music. Those problems arise as we seek to bring the following traits together:

- smooth, independent melodic lines

- unity and blending, what we might call tonal fusion (the preference for simultaneous notes to form a consonant sound)

- variety to create interest

- direction and motion over time, creating a journey that resolves to a satisfying conclusion (i.e. a goal, or home).

These traits are based in human perception and cognition, but they are often in conflict in specific musical moments and need to be balanced over the course of larger passages and complete works. Counterpoint will help us begin a practice of working within the framework of such a balance.

Finally, despite all of it’s abstractions, it’s still best to treat your counterpoint exercises as miniature compositions and to perform them—preferably with a partner or group using voices and/or instruments where possible—so that the ear, the fingers, the throat, and ultimately the mind can internalize the sound, sight, and feel of how musical lines work and combine.

Consonance and Dissonance in Tonal and Modal Music

The subject of consonance and dissonance is a relative one and is one that goes beyond mere definitions of the terms. Remember: Context matters. A review of some of the basic concepts is covered in a chapter in the fundamentals portion of this text.

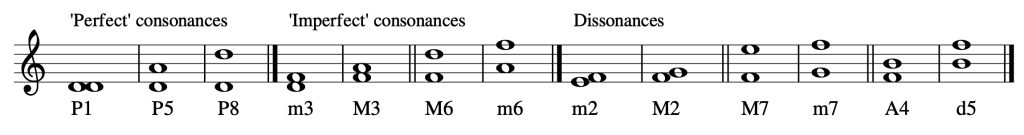

For our purposes, in the study of counterpoint, we further distinguish between consonances and dissonances as follows:

- Perfect consonances (perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves)

- Imperfect consonances (major and minor thirds and sixths)

- Dissonances (all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals)

Each category is summarized in Example 1:

What about the Perfect Fourth?

The perfect fourth has a special status in species counterpoint depending on where it appears in the musical texture. Basically, the interval of a perfect fourth is considered dissonant when it involves the lowest voice in the texture in relationship to the voice(s) above, but is consonant when it occurs between any two upper voices. As this survey of species counterpoint will only cover two-voice musical textures, all fourths will be classed as dissonant.[1]

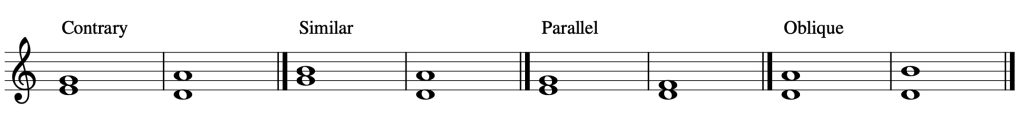

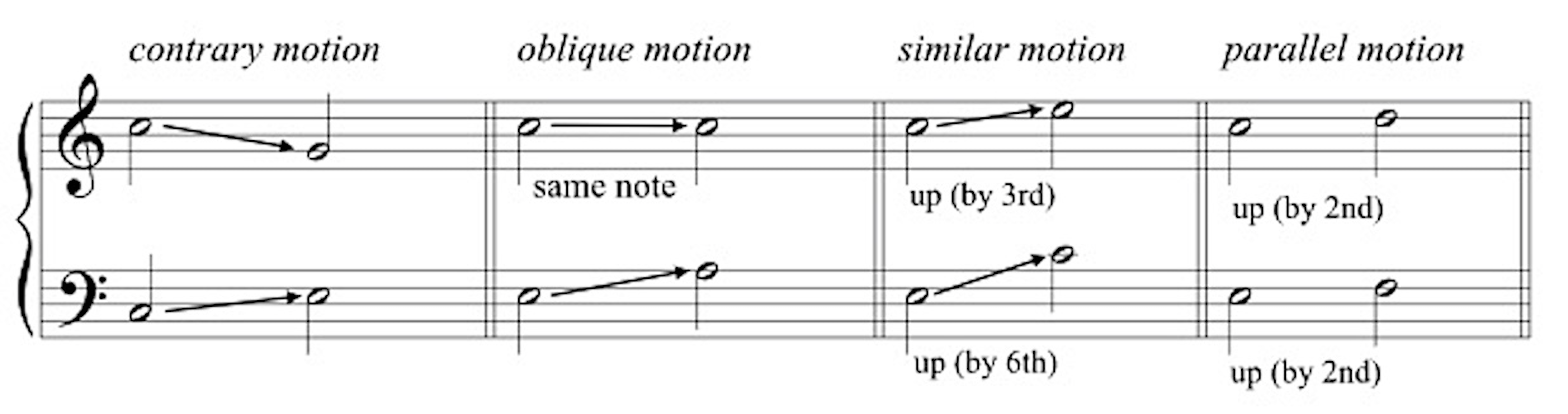

The Four Types of Voice Motion

Species counterpoint also concerns the motion between melodic lines (demonstrated in Examples 2A and B below):

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same distance, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

Guidelines for Melodic and Harmonic Writing in Two-Voice Counterpoint

In species counterpoint, we both write and combine melodic lines. The following set of guidelines (some might say “rules” but we are not going to use that term) are invoked in all the species. Counterpoint specifically calls one’s attention to both dimensions in a given musical texture: the melodic dimension (the melody), and the harmonic dimension (the two voices working together to imply a sense of harmony in motion).

Melodic writing: Horizontal (melodic) intervals

- Approach the final octave/unison of each phrase by step (stepwise motion).

- Limit the number of:

- consecutive, repeated notes: the same pitch more than once in a row (and absolutely not more than three)

- non-consecutive repeated notes: the same pitch more than once across any complete phrase

- consecutive skips or leaps. Try to separate them with stepwise motion, and “smooth out” leaps (and even skips) where possible with a stepwise move in the opposite direction.

- non-consecutive leaps: the total number of leaps within a short span, even if they’re not successive

- consecutive repeated pairs of generic intervals: the same interval size (e.g., second) even if not the same specific interval (minor second). This type of thing is what can lead to instant boredom and just sounds like the melody is doing nothing interesting

- Control the melodic climax (the highest note in your melody)

- Aim for exactly one unique climax in each phrase

- Avoid ending on a climax

- Preferably leap to a climax

- Avoid the two parts reaching their respective climax pitches at the same time

- Avoid melodic leaps of:

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

- sixths, except perhaps the ascending minor sixth. These must be returned in the opposite direction by stepwise motion.

- any interval larger than an octave

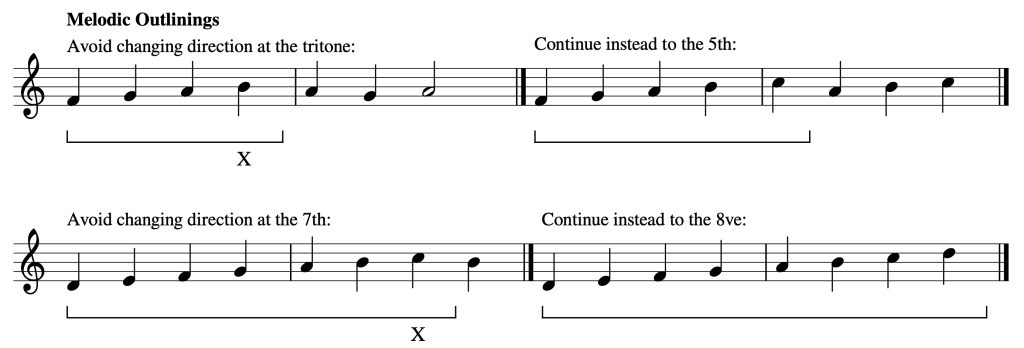

- Also avoid outlining (Example 4):

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

Harmonic writing: Vertical (harmonic) intervals and the combination of the two parts

- The first interval should be a perfect unison, fifth, or octave

- The last interval should be a perfect unison or octave (not a fifth).

- Restrict the total gap between parts to no more than a twelfth (compound fifth) maximum, and try where possible to keep the parts within an octave for the most part.

- Avoid “overlapping” parts (where the nominally “upper” part goes below the “lower” one). We call this voice crossing.

- Try to avoid:

- Parallel motion by octaves: when two parts start an octave apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end an octave apart

- Parallel motion by fifths: when two parts start a perfect fifth apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end a perfect fifth apart

- Also try to avoid:

- direct fifths and octaves: when two parts begin any interval apart and move in the same direction to a perfect fifth or octave

- unisons at any point in the phrase other than at the very beginning and/or very end. Doing so will give the impression that the phrase has ended too soon.

Listening: Examples of 16th Century Vocal Music and Counterpoint

Further Reading and Exploration

- Huron, David. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

- George Russell's Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (1959, pg. 3) and Paul Hindemith's The Craft of Musical Composition: Book 1 (1984, pg. 53) assert that perfect fourths are unstable via "tonic redistribution." Though having different reasons, both come to the conclusion that we perceive the upper tone as the redistributed tonic, indicating the interval dissonant both perceptually and written. ↵

A traditional approach to music composition pedagogy focused on counterpoint as a way of learning to think of music horizontally (melodically) and vertically (harmonically) simultaneously. Consists of five “species,” each of which focuses on a single compositional element.

Perfect octaves (twelve semitones), perfect unisons (zero semitones), and perfect fifths (seven semitones). Perfect fourths (five semitones) are sometimes considered a perfect consonance, sometimes a dissonance; this depends on the context.

Thirds or sixths with major or minor quality. These intervals are found in higher overtones in the harmonic series from a given fundamental and have a more distant relationship in terms of frequency ratios.

Intervals and chord tones that are more distantly related than consonances in the harmonic series and have a perceived quality of auditory roughness.

A form of motion between two voices when they move melodically in opposite directions relative to one another—that is, one voice moves up and the other moves down.

A type of motion between two voices when they move melodically in relation to each other in the same direction (either upward or downward) while the distance (harmonic interval) changes.

A type of voice motion when two voices move in the same direction in relation to each other and move by the same melodic interval and, thus, retain the same harmonic interval—for example, both voices move upward by a melodic second.

A type of voice motion when one voice moves melodically while another voice remains on the same pitch

A rhythmic phenomenon in which the hierarchy of the underlying meter is contradicted through surface rhythms. Syncopation is usually created through accents and/or longer durations.

the art or technique of setting, writing, or playing a melody or melodies in conjunction with another, according to fixed rules. Literal meaning is "point against point" which we interpret as "note against note"

The relative position of a note within a diatonic mode (scale). Scale degrees are indicated with a number, 1–7, that shows this position relative to the tonic (tonal/modal center) of that mode.

1. A scale, mode, or collection that follows the pattern of whole and half steps W–W–H–W–W–W–H, or any rotation of that pattern.

2. Belonging to the local key (as opposed to "chromatic").

A perceived quality of auditory roughness in an interval or chord, relative to the surrounding musical texture.

A perceived stability or smoothness in a chord or interval relative to the surrounding musical texture.

melodic motion to the next adjacent note (pitch) in the mode/scale (scale degree), either up or down.

a melodic interval of a third, named as such because often a note between is skipped in the mode/scale (example, C going to E skips over the D in between)

A melodic interval greater than a third (fourths, fifths, octaves, etc.)

The number of scale steps between notes of a collection or scale.

When a higher voice part moves below a lower voice part. In strict SATB style, the ranges of voices should not cross; the soprano must always be higher than the alto, the alto must always be higher than the tenor, and the tenor must be higher than the bass.

Similar motion into either a fifth or octave. Also called hidden fifths / hidden octaves.