Approaches to Sociological Research

- Define and describe the scientific method

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research

- Understand the function and importance of an interpretive framework

- Define what reliability and validity mean in a research study

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered workplace patterns that have transformed industries, family patterns that have enlightened family members, and education patterns that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

It might seem strange to use scientific practices to study social trends, but, as we shall see, it’s extremely helpful to rely on systematic approaches that research methods provide. Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the sociologist forms the question, he or she proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

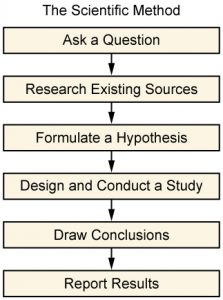

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scholarship.

But just because sociological studies use scientific methods does not make the results less human. Sociological topics are not reduced to right or wrong facts. In this field, results of studies tend to provide people with access to knowledge they did not have before—knowledge of other cultures, knowledge of rituals and beliefs, or knowledge of trends and attitudes. No matter what research approach they use, researchers want to maximize the study’s reliability, which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group. Researchers also strive for validity, which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. Returning to the crime rate during a full moon topic, reliability of a study would reflect how well the resulting experience represents the average adult crime rate during a full moon. Validity would ensure that the study’s design accurately examined what it was designed to study, so an exploration of adult criminal behaviors during a full moon should address that issue and not veer into other age groups’ crimes, for example.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze the data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This doesn’t mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in a particular study.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963).

Typically, the scientific method starts with these steps—1) ask a question, 2) research existing sources, 3) formulate a hypothesis—described below.

Ask a Question

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, describe a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geography and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. That said, happiness and hygiene are worthy topics to study. Sociologists do not rule out any topic, but would strive to frame these questions in better research terms.

That is why sociologists are careful to define their terms. In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?” Now we see that this research question has two variables that are believed to be related.

- Independent Variable (IV)- This is the ‘driver’ variable, the one creating change

- Dependent Variable (DV)- the is the ‘receiving’ variable, the one that is changed

The question above has personal hygiene habits as shaped by the cultural value placed on appearance. IV = the cultural value placed on appearance and DV = personal hygiene.

All of your sociological research questions need an independent variable and a dependent variable.

When forming basic research questions, sociologists develop an operational definition, that is, they define the concept in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing a variable of the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner.

The operational definition must be valid, appropriate, and meaningful. And it must be reliable, meaning that results will be close to uniform when tested on more than one person. For example, “good drivers” might be defined in many ways: those who use their turn signals, those who don’t speed, or those who courteously allow others to merge. But these driving behaviors could be interpreted differently by different researchers and could be difficult to measure. Alternatively, “a driver who has never received a traffic violation” is a specific description that will lead researchers to obtain the same information, so it is an effective operational definition.

Research Existing Sources: A Literature Review

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library and a thorough online search will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted on the topic at hand and enables them to position their own research to build on prior knowledge. In conducting a literature review, sociological researchers should be paying attention to these three aspects of research in all of the literature they examine:

- method used

- theory used

- topic of study

Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study hygiene and its value in a particular society, a researcher might sort through existing research and unearth studies about child-rearing, vanity, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and cultural attitudes toward beauty. It’s important to sift through this information and determine what is relevant. Using existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve studies’ designs.

Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an assumption about how two or more variables are related; it makes a conjectural statement about the relationship between those variables. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another.

For example, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Or rephrased, a child’s sense of self-esteem depends, in part, on the quality and availability of hygienic resources.

Of course, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. Perhaps a sociologist believes that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will automatically increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two topics, or variables, is not enough; their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Think about some other examples: How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. | Affordable Housing | Homeless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighborhood. | Police Patrol Presence | Safer Neighborhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of observation, the higher the public awareness. | Observation | Public Awareness |

At this point, a researcher’s operational definitions help measure the variables. In a study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” Another operational definition might describe “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” Those definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

Just because a sociologist forms an educated prediction of a study’s outcome doesn’t mean data contradicting the hypothesis aren’t welcome. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns.

In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While it has become at least a cultural assumption that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results will vary.

Once the preliminary work is done, it’s time for the next research steps: designing and conducting a study and drawing conclusions. These research methods are discussed below.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework. While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective, seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects. This type of researcher also learns as he or she proceeds and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Summary

Using the scientific method, a researcher conducts a study in five phases: asking a question, researching existing sources, formulating a hypothesis, conducting a study, and drawing conclusions. The scientific method is useful in that it provides a clear method of organizing a study. Some sociologists conduct research through an interpretive framework rather than employing the scientific method.

Scientific sociological studies often observe relationships between variables. Researchers study how one variable changes another. Prior to conducting a study, researchers are careful to apply operational definitions to their terms and to establish dependent and independent variables.

A LOOK AT DATA:

Redneck Revolt: Rethinking Discourse and Identity in Activism

Redneck Revolt is a now defunct social movement that challenged capitalism and racial injustice, while advocating for gun rights. After the collapse of Redneck Revolt, I interviewed N = 9 former participants from local chapters around the United States. The primary research questions the study was most interested in, include:

- How do the individuals view their own identity and role in the movement?

- How is discourse used in the movement?

- How does the identity of the activists shape the perception and goals of the movement?

- How does this political-cultural moment in the United States inform this activism?

What follows is a short essay that used the N = 9 interviews to provide context for the movement, and to highlight the voices of the activists. The indented quoted segments are direct quotes from interviews. Each number refers to a specific participant. Their names are not used to protect their identity. Read through the essay, then consider the questions below, using what you now know about sociology methods, ethics, and social context.

ESSAY:

There have been armed anarchist-based movements on the left for decades in the United States. This is not new. What is new is a 21st century move to anarchist based armed Left movements that are steeped in intersectional discourse with nuanced approaches to tactical innovation. Redneck Revolts starts in 2009, goes in abeyance, re-emerges in 2016, and falls apart by 2019. It was a national activist organization that advocated for the downfall of capitalism through the elimination of racism. They framed their work as connected to a long historical lineage with roots in Marxist ideology. As a member stated:

“The rights to community are inherited – it’s not something the state gives you.” (1).

I wrote about Redneck Revolt earlier, (Rothschild, 2019) and since then was given access to interview a very small sample of members from chapters across the county. The context for these activists who participated for various lengths of time between 2015-2019 – is that in 2017 – prior to Charlottesville, democracy in the U.S. had already failed (Smolla, 2020). The N=9 activists I interviewed that were affiliated with Redneck Revolt primarily joined around 2017 and stayed until its demise in 2019. The short period of time does not minimize the power of the movement for these activists, and why it is important to continue to examine. The narratives of the subjects interviewed provide more insight into what drew them to this movement, how they make sense of activism in the United States today, (Faysee, 2018) what their experience in the movement was, and what their take aways are now, after the decline of the movement.

When questioned about what they were looking for and why they joined this organization, all offered that they found the group online when they were searching for like-minded people. They were drawn to the movement because they viewed it as a radical anarchist organization that was ‘horizontal’ in leadership, emphasizing the importance of community over capitalism. The horizontal nature of the movement was a draw because these members were aware of the pitfalls of more ‘top-down’ social movement infrastructure and leadership. They knew of movements that were hierarchal, as well as those that were leaderless (Occupy Movement), and what the consequences of each structure were.

The participants ranged in age from 23-50, and none identified as woman or female, though several would be labeled that way in mainstream American society. This defies the representation that the movement is white working-class men exclusively. A few of the non-binary respondents were initially skeptical about the inclusion of guns in the movement and saw that as a limitation of the movement. Once they were engaged in the movement, they ‘came around’ and changed their views on guns broadly from advocates of ‘gun control’ to seeing the use of firearms as necessary to fight the state and protect the powerless. The activists received overall support from family and friends for their affiliation with the organization, even though they all came from diverse racial, ethnic, political, and regional backgrounds, with family members from a range of social classes. All people interviewed saw themselves as solidly part of or central to the organization. Some of the members had positions in the national chapter as well as in their specific local state chapters. They were drawn to the history of fighting capitalist oppression and a few mentioned groups such as the Young Patriots, white Appalachian activists who aligned with the Black Panthers in the 1960s.

Overall, they supported the name Redneck Revolt, even though the sample illustrated that they were much more diverse than media had portrayed the activists. Non-binary, queer, and racially and class diverse, the members came from different starting points, but shared anti-capitalist tendencies and embraced the fight for racial justice. Overall, there are very high levels of education among its former members. All the subjects I spoke with had completed college, and some had additional education. In addition to formal education, many had been involved in informally educating themselves through intellectual readings steeped in Marx and Lenin. Many of the younger activists interviewed were very conscious about their identities (Earl, et al, 2017) and articulated who they were and how they presented themselves, even when they were not prompted to do so. This was true among the activists across varied regions that were interviewed and seemed to illustrate a bit of the micro-culture of the movement. Despite the racial, class, and sexuality diversity, many felt the organization was still ‘run by’ a white cis-gender man and woman.

Their activism was two-fold: challenging the state/capitalism and fascism (some see this as 2 or 1). Racism was embedded in both, and they want to challenge both. They argued that both poor white people and poor people of color are fighting against the same enemy – the wealthy. (Bray, 2017). They framed their work as attacking white supremacy. The activists understood white supremacy as central to capitalism. The right to bear arms is entwined in the right to overthrow the state, if necessary. When asked to explain their activism, two different participants shared:

“It is radical politics that is in the same historical family that many of us wanted to participate in.” (5)

“I wanted something above ground that was visible and transparent. I wanted people to be connected to safe community defense.” (8)

Class and community-defense were much used phrases that the activists used when discussing their participation. For these activists, many ‘came to’ progressive politics, and were aware of how others would see them.

“I grew up outside of the Left. I was working-class. We realized to get people in we had to ‘make a plan’. (9)

Community defense was viewed as direct action. For them – to affect change requires guns. All emphasized the importance of firearms for themselves and training for communities who historically have not had access to firearms training. Ideology on what to do with arming is split between viewing guns as tools for self-empowerment and as tools for aiding others in community. Guns provided them the ability to directly fight fascism at its roots at all costs. A few respondents commented that sometimes the left leaning allies were not comfortable with the use and presence of firearms. The firearms of choice for members range from AK 47 machine guns to older Russian rifles that evoke a call to how firearms have been used in the past. Members did work at gaining trust with those on the left that did not carry firearms. They were ‘protecting’ and not initiating violence – and for many of the members, this distances them from Antifa. Though two subjects I spoke to aligned themselves with antifa ideology. Overall, Redneck Revolt activists saw the 2nd Amendment as not just right. They see gun control as racist – disarming black people. One convert to the use of guns as a tool in activism reported: “They showed me that guns were not the tool of the oppressor.” (1)

In addition to the use of guns, central to Redneck Revolt was what they called ‘counter-recruiting’. The Marxist rhetoric framed community and success as only possible with a coalition across classes, and identities to challenge the built-in oppression of capitalism. For Redneck Revolt this meant ‘working with’ white working-class people who might be ‘taught’ to embrace an alt-right or white supremacist ideology. “I didn’t want to do it [counter-recruiting] because I distrusted these people. But you are doing a great service by organizing and changing the way the alt-right think.” (6) Counter-recruiting was dreaded and hard, but it also helped bind the members together, and distinguished them from other Left leaning movements that centered firearms. “No one else was counter-recruiting…It really felt like a community.” (4)

In their counter-recruiting work, they occupied spaces that are often associated with white working-class places: country music concerts, flea markets, gun shows, NASCAR events and rodeos. In these spaces, they stood against white supremacy as an aboveground militant formation that was an anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-fascist group that used direct action to protect the marginalized and argued for the necessity of a revolution, while drawing attention to limits of liberalism. They saw themselves as challenging white nationalist groups, (Sonnie, 2011), arguing that these organizations do not ‘provide a way out’ for white working-class folks, but rather that these white nationalist organizations create more racial divisions while building up the capitalist enterprise. These tactics of Redneck Revolt were designed specifically to connect differing populations with new practices. Multiple responses to white nationalist demonstrations have come out of this as well. A way that the organization tried to practice this was to populate and support events that were not ‘theirs’ to connect to other groups. In the counter-recruiting, particular messaging was altered based on the audience. The necessity of racial and transgender justice might be geared towards rural whites, while the firearms trainings were for people who are typically shut out of gun culture in the United States: women and people of color.

In addition to the work of counter-recruiting, Redneck Revolt engaged in community survival projects and Mutual Aid. The community survival projects included firearm engagement, but also involved creating spaces in rural communities for Pride Parades. The mutual aid component included free stores, meet-ups, and attention to redistributing resources within their own communities. The attention to mutual aid was a way to build community and support as they garnered trust with people they were engaged in recruiting and/or working with. Mutual aid was also a deliberate means to challenge the tenets of capitalism, shunning consumerism in favor of cooperation and collectives. This was a clear activist practice of the group, more present in some regions, (Maine and California), according to my respondents.

Social media was a primary tool of tactical innovation (Kim and Lim, 2019) for the activists. Many participated in memes that initially showed their alliances to, and later their questioning or disdain for Redneck Revolt. Discord was used a way to communicate within and across chapters. Initially, the ability for all members to participate on Discord led to a sense of a ‘leaderless’ organization. The emphasis on a horizontal model of equity was strong initially, but calls of sexism, questions of sexual assault, and insular communication among select members led to a feeling of a more traditional ‘vertical’ organization, with hierarchy ‘built in’. This ultimately led to the downfall of the organization. As one member recalled: “Social media created and destroyed Redneck Revolt.” (9)

Everyone was very savvy and aware of their individual media presence, (Carty and Barron, 2018) and Redneck Revolt’s as well. They saw it as a double edge sword. On the one hand, they did get media coverage because of the perceived juxtaposition between who they are, and what they do. However, this coverage was often reductive and sensationalized, resulting in essentialized narratives of the members and the mission. At times this created more social distance between themselves as a group, as well as between members and society at large.

By the time I spoke to the participants in the Spring and Summer of 2022, no one had remained active in the organization, and the movement was defunct. Some cited social media, others misogyny, still others the press, as the primary reason of the collapse. However, many argued that there was a pseudo-intellectualism that was not healthy for their movement in the long run. Another spoke directly about Lenin and Marxism in reference to intellectualism as having the ability to harm a movement. For the most part though, most of the members spoken to, left the movement because they felt disillusioned with Redneck Revolt as a whole. Two reported not knowing what the movement stood for anymore. One was trying to keep the local chapter he was involved in afloat with a new name, another was repeatedly ‘doxed’, and was unsure if it was from people within or beyond the movement. “People who spend time on the internet have a warped sense of what is reasonable and what is bat-shit insane.” (5) As community eroded, so did the clear message of protest and the purpose of the movement: “People just don’t get collective action.” (5). “It was not in the Mission Statement to be paternalistic white people protecting people of color – but, anyway I think it happened.” (9)

However, despite the decline of the movement, everyone claimed that they are still connected to at least someone in the movement today – and see themselves forever part of a community, even if some of them have never met each other past the keyboard. Many viewed the movement overall as a success. A few pointed out that the success or ‘footprint’ would not be seen until people could look back and see how much Redneck Revolt accomplished by countering militia movements, emphasizing firearm training, and counter-recruiting.

References:

Bray, Mark (2017). Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing, 2017.

Carty, Victoria and Francisco G. Reynoso Barron. “Social Movement and new technology: The dynamics of cyberactivism in the digital age.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Social Movements and Social Transformation. London: Palgrave Publishers, 2018: 373-397, 2018.

Earl, Jennifer and Thomas Maher and Thomas Elliot. “Youth, Activism, and Social Movements.” Sociology Compass. Volume 11, Number 4, 2017: 1-14.

Faysse, Nicholas. “Finding common ground between theories of collective action: The potential of analyses at a meso-scale.” International Journal of the Commons. Volume 11, Number 2, 2017: 928-949.

Hyun-soo Kim, Harris and Chaeyoan Lim. “From Virtual Space to Public Space: The Roles of Online Political Activism in Protest Participation During Arab Spring. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 2019, Volume 60, Number 6, 2019: 409-434.

Rothschild, Teal. “Multiplicity in movements: the case for Redneck Revolt.” Contexts. American Sociological Association Journal. Summer 2019, Volume 18, Issue 3, pp.57-59, 2019.

Smolla, Rodney A. “Rednecks and Saint Paul” in Confessions of a Free Speech Lawyer: Charlottesville and the Politics of Hate. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020; 243-246.

Sonnie, Amy and James Tracy. Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishers, 2011

Student Questions:

- How do the primary questions that guide this research lend themselves to semi-structured interviews? Are there other methods I could have employed, given these research questions?

- Why do you think ‘context’ and ‘history’ are so important to this particular group of activists?

- What are some examples of how the narratives (direct quotes from subjects) illustrate how these activists viewed their activism?

- Why do you think the participants emphasize aspects of their identity so much?

- Try to use their particular (micro) experience with social media and activism to develop a broader more generalized research project (macro) that focuses on social media and activism.

- Try and find some narratives that show emotions. The subjects might not say “I am angry”, for example, but there are emotional themes that are present here. Try and find some individual examples, and then locate any emotional themes across interviews.

Section Quiz

Further Research

For a historical perspective on the scientific method in sociology, read “The Elements of Scientific Method in Sociology” by F. Stuart Chapin (1914) in the American Journal of Sociology: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Method-in-Sociology

References

Arkowitz, Hal, and Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2009. “Lunacy and the Full Moon: Does a full moon really trigger strange behavior?” Scientific American. Retrieved October 20, 2014 (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lunacy-and-the-full-moon).

Berger, Peter L. 1963. Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Merton, Robert. 1968 [1949]. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

“Scientific Method Lab,” the University of Utah, http://aspire.cosmic-ray.org/labs/scientific_method/sci_method_main.html.

an established scholarly research method that involves asking a question, researching existing sources, forming a hypothesis, designing and conducting a study, and drawing conclusions

a sociological research approach that seeks in-depth understanding of a topic or subject through observation or interaction; this approach is not based on hypothesis testing

a measure of a study’s consistency that considers how likely results are to be replicated if a study is reproduced

the degree to which a sociological measure accurately reflects the topic of study

a testable proposition

variables that cause changes in dependent variables

a variable changed by other variables

specific explanations of abstract concepts that a researcher plans to study

a scholarly research step that entails identifying and studying all existing studies on a topic to create a basis for new research