Pop Culture, Subculture, and Cultural Change

- Discuss the roles of both high culture and pop culture within society

- Differentiate between subculture and counterculture

- Explain the role of innovation, invention, and discovery in culture

It may seem obvious that there are a multitude of cultural differences between societies in the world. After all, we can easily see that people vary from one society to the next. It’s natural that a young woman from rural Kenya would have a very different view of the world from an elderly man in Mumbai—one of the most populated cities in the world. Additionally, each culture has its own internal variations. Sometimes the differences between cultures are not nearly as large as the differences inside cultures.

Popular Culture

The term popular culture refers to the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in mainstream society. Popular culture events might include a parade, a baseball game, or the season finale of a television show. Rock and pop music—“pop” is short for “popular”—are part of popular culture. Popular culture is often expressed and spread via commercial media such as radio, television, movies, the music industry, publishers, and corporate-run websites. Unlike high culture, reserved for the elite, popular culture is known and accessible to most people. You can share a discussion of favorite football teams with a new coworker or comment on American Idol when making small talk in line at the grocery store. But if you tried to launch into a deep discussion on the classical Greek play Antigone at a subway station, few members of U.S. society today would be familiar with it.

Subculture and Counterculture

A subculture is just what it sounds like—a smaller cultural group within a larger culture; people of a subculture are part of the larger culture but also share a specific identity within a smaller group.

Thousands of subcultures exist within the United States. Ethnic and racial groups share the language, food, and customs of their heritage. Other subcultures are united by shared experiences. Biker culture revolves around a dedication to motorcycles. Some subcultures are formed by members who possess traits or preferences that differ from the majority of a society’s population. The body modification community embraces aesthetic additions to the human body, such as tattoos, piercings, and certain forms of plastic surgery. In the United States, adolescents often form subcultures to develop a shared youth identity. Alcoholics Anonymous offers support to those suffering from alcoholism. But even as members of a subculture band together, they still identify with and participate in the larger society.

Sociologists distinguish subcultures from countercultures, which are a type of subculture that reject some of the larger culture’s norms and values. In contrast to subcultures, which operate relatively smoothly within the larger society, countercultures might actively defy larger society by developing their own set of rules and norms to live by, sometimes even creating communities that operate outside of greater society.

Cults, a word derived from culture, are also considered counterculture group. The group “Yearning for Zion” (YFZ) in Eldorado, Texas, existed outside the mainstream and the limelight, until its leader was accused of statutory rape and underage marriage. The sect’s formal norms clashed too severely to be tolerated by U.S. law, and in 2008, authorities raided the compound and removed more than two hundred women and children from the property.

Skinny jeans, chunky glasses, and T-shirts with vintage logos—the American hipster is a recognizable figure in the modern United States. Based predominately in metropolitan areas, sometimes clustered around hotspots such as the Williamsburg neighborhood in New York City, hipsters define themselves through a rejection of the mainstream. As a subculture, hipsters spurn many of the values and beliefs of U.S. culture and prefer vintage clothing to fashion and a bohemian lifestyle to one of wealth and power. While hipster culture may seem to be the new trend among young, middle-class youth, the history of the group stretches back to the early decades of the 1900s.

Where did the hipster culture begin? In the early 1940s, jazz music was on the rise in the United States. Musicians were known as “hepcats” and had a smooth, relaxed quality that went against upright, mainstream life. Those who were “hep” or “hip” lived by the code of jazz, while those who were “square” lived according to society’s rules. The idea of a “hipster” was born.

The hipster movement spread, and young people, drawn to the music and fashion, took on attitudes and language derived from the culture of jazz. Unlike the vernacular of the day, hipster slang was purposefully ambiguous. When hipsters said, “It’s cool, man,” they meant not that everything was good, but that it was the way it was.

By the 1950s, the jazz culture was winding down and many traits of hepcat culture were becoming mainstream. A new subculture was on the rise. The “Beat Generation,” a title coined by writer Jack Kerouac, were anti-conformist and anti-materialistic. They were writers who listened to jazz and embraced radical politics. They bummed around, hitchhiked the country, and lived in squalor.

The lifestyle spread. College students, clutching copies of Kerouac’s On the Road, dressed in berets, black turtlenecks, and black-rimmed glasses. Women wore black leotards and grew their hair long. Herb Caen, a San Francisco journalist, used the suffix from Sputnik 1, the Russian satellite that orbited Earth in 1957, to dub the movement’s followers “Beatniks.”

As the Beat Generation faded, a new, related movement began. It too focused on breaking social boundaries, but it also advocated freedom of expression, philosophy, and love. It took its name from the generations before; in fact, some theorists claim that Beats themselves coined the term to describe their children. Over time, the “little hipsters” of the 1970s became known simply as “hippies.”

Today’s generation of hipsters rose out of the hippie movement in the same way that hippies rose from Beats and Beats from hepcats. Although contemporary hipsters may not seem to have much in common with 1940s hipsters, the emulation of nonconformity is still there. In 2010, sociologist Mark Greif set about investigating the hipster subculture of the United States and found that much of what tied the group members together was not based on fashion, musical taste, or even a specific point of contention with the mainstream. “All hipsters play at being the inventors or first adopters of novelties,” Greif wrote. “Pride comes from knowing, and deciding, what’s cool in advance of the rest of the world. Yet the habits of hatred and accusation are endemic to hipsters because they feel the weakness of everyone’s position—including their own” (Greif 2010). Much as the hepcats of the jazz era opposed common culture with carefully crafted appearances of coolness and relaxation, modern hipsters reject mainstream values with a purposeful apathy.

Young people are often drawn to oppose mainstream conventions, even if in the same way that others do. Ironic, cool to the point of noncaring, and intellectual, hipsters continue to embody a subculture, while simultaneously impacting mainstream culture.

As the hipster example illustrates, culture is always evolving. Moreover, new things are added to material culture every day, and they affect nonmaterial culture as well. Cultures change when something new (say, railroads or smartphones) opens up new ways of living and when new ideas enter a culture (say, as a result of travel or globalization).

Culture lag can also cause tangible problems. The infrastructure of the United States, built a hundred years ago or more, is having trouble supporting today’s more heavily populated and fast-paced life. Yet there is a lag in conceptualizing solutions to infrastructure problems. Rising fuel prices, increased air pollution, and traffic jams are all symptoms of culture lag. Although people are becoming aware of the consequences of overusing resources, the means to support changes takes time to achieve.

This video was taken from the “Sociology Crash Course” series of videos http://thecrashcourse.com and created by Cindy Hager in collaboration with the Alexandria Technical Community College.

Summary

Sociologists recognize high culture and popular culture within societies. Societies are also comprised of many subcultures—smaller groups that share an identity. Countercultures reject mainstream values and create their own cultural rules and norms. Through invention or discovery, cultures evolve via new ideas and new ways of thinking. In many modern cultures, the cornerstone of innovation is technology. Technology is also responsible for the spread of both material and nonmaterial culture that contributes to globalization.

Section Quiz

Short Answer

Identify several examples of popular culture and describe how they inform larger culture. How prevalent is the effect of these examples in your everyday life?

Consider some of the specific issues or concerns of your generation. Are any ideas countercultural? What subcultures have emerged from your generation? How have the issues of your generation expressed themselves culturally? How has your generation made its mark on society’s collective culture?

What are some examples of cultural lag that are present in your life? Do you think technology affects culture positively or negatively? Explain.

Popular culture meets counterculture in this article as Oprah Winfrey interacts with members of the Yearning for Zion cult. Read about it here: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Oprah

References

Greif, Mark. 2010. “The Hipster in the Mirror.” New York Times, November 12. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/14/books/review/Greif-t.html?pagewanted=1).

Ogburn, William F. 1957. “Cultural Lag as Theory.” Sociology & Social Research 41(3):167–174.

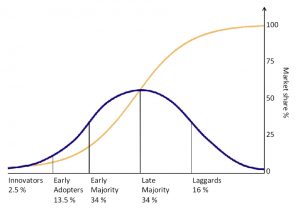

Rogers, Everett M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. Glencoe: Free Press.

Scheuerman, William. 2010. “Globalization.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Revised 2014. Zalta, Summer. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2010/entries/globalization/).

mainstream, widespread patterns among a society’s population

the cultural patterns of a society’s elite

groups that share a specific identification, apart from a society’s majority, even as the members exist within a larger society

groups that reject and oppose society’s widely accepted cultural patterns

the gap of time between the introduction of material culture and nonmaterial culture’s acceptance of it