Variations in Family Life

- Recognize variations in family life

- Understand the prevalence of single parents, cohabitation, same-sex couples, and unmarried individuals

- Discuss the social impact of changing family structures

The combination of husband, wife, and children that 99.8 percent of people in the United States believe constitutes a family is not representative of 99.8 percent of U.S. families. According to 2010 census data, only 66 percent of children under seventeen years old live in a household with two married parents. This is a decrease from 77 percent in 1980 (U.S. Census 2011). This two-parent family structure is known as a nuclear family, referring to married parents and children as the nucleus, or core, of the group. Recent years have seen a rise in variations of the nuclear family with the parents not being married. Three percent of children live with two cohabiting parents (U.S. Census 2011).

Single Parents

Single-parent households are on the rise. In 2010, 27 percent of children lived with a single parent only, up from 25 percent in 2008. Of that 27 percent, 23 percent live with their mother and three percent live with their father. Ten percent of children living with their single mother and 20 percent of children living with their single father also live with the cohabitating partner of their parent (for example, boyfriends or girlfriends).

Stepparents are an additional family element in two-parent homes. Among children living in two-parent households, 9 percent live with a biological or adoptive parent and a stepparent. The majority (70 percent) of those children live with their biological mother and a stepfather. Family structure has been shown to vary with the age of the child. Older children (fifteen to seventeen years old) are less likely to live with two parents than adolescent children (six to fourteen years old) or young children (zero to five years old). Older children who do live with two parents are also more likely to live with stepparents (U.S. Census 2011).

In some family structures, a parent is not present at all. In 2010, three million children (4 percent of all children) lived with a guardian who was neither their biological nor adoptive parent. Of these children, 54 percent live with grandparents, 21 percent live with other relatives, and 24 percent live with nonrelatives. This family structure is referred to as the extended family and may include aunts, uncles, and cousins living in the same home. Foster parents account for about a quarter of nonrelatives. The practice of grandparents acting as parents, whether alone or in combination with the child’s parent, is becoming widespread among today’s families (De Toledo and Brown 1995). Nine percent of all children live with a grandparent, and in nearly half those cases, the grandparent maintains primary responsibility for the child (U.S. Census 2011). A grandparent functioning as the primary care provider often results from parental drug abuse, incarceration, or abandonment. Events like these can render the parent incapable of caring for his or her child.

Changes in the traditional family structure raise questions about how such societal shifts affect children. U.S. Census statistics have long shown that children living in homes with both parents grow up with more financial and educational advantages than children who are raised in single-parent homes (U.S. Census 1997). Parental marital status seems to be a significant indicator of advancement in a child’s life. Children living with a divorced parent typically have more advantages than children living with a parent who never married; this is particularly true of children who live with divorced fathers. This correlates with the statistic that never-married parents are typically younger, have fewer years of schooling, and have lower incomes (U.S. Census 1997). Six in ten children living with only their mother live near or below the poverty level. Of those being raised by single mothers, 69 percent live in or near poverty compared to 45 percent for divorced mothers (U.S. Census 1997). Though other factors such as age and education play a role in these differences, it can be inferred that marriage between parents is generally beneficial for children.

Cohabitation

Living together before or in lieu of marriage is a growing option for many couples. Cohabitation, when a man and woman live together in a sexual relationship without being married, was practiced by an estimated 7.5 million people (11.5 percent of the population) in 2011, which shows an increase of 13 percent since 2009 (U.S. Census 2010). This surge in cohabitation is likely due to the decrease in social stigma pertaining to the practice. In a 2010 National Center for Health Statistics survey, only 38 percent of the 13,000-person sample thought that cohabitation negatively impacted society (Jayson 2010). Of those who cohabitate, the majority are non-Hispanic with no high school diploma or GED and grew up in a single-parent household (U.S. Census 2010).

Cohabitating couples may choose to live together in an effort to spend more time together or to save money on living costs. Many couples view cohabitation as a “trial run” for marriage. Today, approximately 28 percent of men and women cohabitated before their first marriage. By comparison, 18 percent of men and 23 percent of women married without ever cohabitating (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The vast majority of cohabitating relationships eventually result in marriage; only 15 percent of men and women cohabitate only and do not marry. About one half of cohabitators transition into marriage within three years (U.S. Census 2010).

While couples may use this time to “work out the kinks” of a relationship before they wed, the most recent research has found that cohabitation has little effect on the success of a marriage. In fact, those who do not cohabitate before marriage have slightly better rates of remaining married for more than ten years (Jayson 2010). Cohabitation may contribute to the increase in the number of men and women who delay marriage. The median age for marriage is the highest it has ever been since the U.S. Census kept records—age twenty-six for women and age twenty-eight for men (U.S. Census 2010).

Same-Sex Couples

The number of same-sex couples has grown significantly in the past decade. The U.S. Census Bureau reported 594,000 same-sex couple households in the United States, a 50 percent increase from 2000. This increase is a result of more coupling, the growing social acceptance of homosexuality, and a subsequent increase in willingness to report it. Nationally, same-sex couple households make up 1 percent of the population, ranging from as little as 0.29 percent in Wyoming to 4.01 percent in the District of Columbia (U.S. Census 2011). Legal recognition of same-sex couples as spouses is different in each state, as only six states and the District of Columbia have legalized same-sex marriage. The 2010 U.S. Census, however, allowed same-sex couples to report as spouses regardless of whether their state legally recognizes their relationship. Nationally, 25 percent of all same-sex households reported that they were spouses. In states where same-sex marriages are performed, nearly half (42.4 percent) of same-sex couple households were reported as spouses.

In terms of demographics, same-sex couples are not very different from opposite-sex couples. Same-sex couple households have an average age of 52 and an average household income of $91,558; opposite-sex couple households have an average age of 59 and an average household income of $95,075. Additionally, 31 percent of same-sex couples are raising children, not far from the 43 percent of opposite-sex couples (U.S. Census 2009). Of the children in same-sex couple households, 73 percent are biological children (of only one of the parents), 21 percent are adopted only, and 6 percent are a combination of biological and adopted (U.S. Census 2009).

While there is some concern from socially conservative groups regarding the well-being of children who grow up in same-sex households, research reports that same-sex parents are as effective as opposite-sex parents. In an analysis of 81 parenting studies, sociologists found no quantifiable data to support the notion that opposite-sex parenting is any better than same-sex parenting. Children of lesbian couples, however, were shown to have slightly lower rates of behavioral problems and higher rates of self-esteem (Biblarz and Stacey 2010).

Staying Single

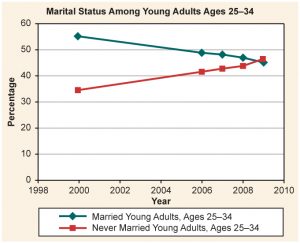

Gay or straight, a new option for many people in the United States is simply to stay single. In 2010, there were 99.6 million unmarried individuals over age eighteen in the United States, accounting for 44 percent of the total adult population (U.S. Census 2011). In 2010, never-married individuals in the twenty-five to twenty-nine age bracket accounted for 62 percent of women and 48 percent of men, up from 11 percent and 19 percent, respectively, in 1970 (U.S. Census 2011). Single, or never-married, individuals are found in higher concentrations in large cities or metropolitan areas, with New York City being one of the highest.

Although both single men and single women report social pressure to get married, women are subject to greater scrutiny. Single women are often portrayed as unhappy “spinsters” or “old maids” who cannot find a man to marry them. Single men, on the other hand, are typically portrayed as lifetime bachelors who cannot settle down or simply “have not found the right girl.” Single women report feeling insecure and displaced in their families when their single status is disparaged (Roberts 2007). However, single women older than thirty-five years old report feeling secure and happy with their unmarried status, as many women in this category have found success in their education and careers. In general, women feel more independent and more prepared to live a large portion of their adult lives without a spouse or domestic partner than they did in the 1960s (Roberts 2007).

The decision to marry or not to marry can be based a variety of factors including religion and cultural expectations. Asian individuals are the most likely to marry while African Americans are the least likely to marry (Venugopal 2011). Additionally, individuals who place no value on religion are more likely to be unmarried than those who place a high value on religion. For black women, however, the importance of religion made no difference in marital status (Bakalar 2010). In general, being single is not a rejection of marriage; rather, it is a lifestyle that does not necessarily include marriage. By age forty, according to census figures, 20 percent of women and 14 of men will have never married (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

It is often cited that half of all marriages end in divorce. This statistic has made many people cynical when it comes to marriage, but it is misleading. Let’s take a closer look at the data.

Using National Center for Health Statistics data from 2003 that show a marriage rate of 7.5 (per 1000 people) and a divorce rate of 3.8, it would appear that exactly one-half of all marriages failed (Hurley 2005). This reasoning is deceptive, however, because instead of tracing actual marriages to see their longevity (or lack thereof), this compares what are unrelated statistics: that is, the number of marriages in a given year does not have a direct correlation to the divorces occurring that same year. Research published in the New York Times took a different approach—determining how many people had ever been married, and of those, how many later divorced. The result? According to this analysis, U.S. divorce rates have only gone as high as 41 percent (Hurley 2005). Another way to calculate divorce rates would be through a cohort study. For instance, we could determine the percentage of marriages that are intact after, say, five or seven years, compared to marriages that have ended in divorce after five or seven years. Sociological researchers must remain aware of research methods and how statistical results are applied. As illustrated, different methodologies and different interpretations can lead to contradictory, and even misleading, results.

Theoretical Perspectives on Marriage and Family

Sociologists study families on both the macro and micro level to determine how families function. Sociologists may use a variety of theoretical perspectives to explain events that occur within and outside of the family.

Functionalism

When considering the role of family in society, functionalists uphold the notion that families are an important social institution and that they play a key role in stabilizing society. They also note that family members take on status roles in a marriage or family. The family—and its members—perform certain functions that facilitate the prosperity and development of society.

Sociologist George Murdock conducted a survey of 250 societies and determined that there are four universal residual functions of the family: sexual, reproductive, educational, and economic (Lee 1985). According to Murdock, the family (which for him includes the state of marriage) regulates sexual relations between individuals. He does not deny the existence or impact of premarital or extramarital sex, but states that the family offers a socially legitimate sexual outlet for adults (Lee 1985). This outlet gives way to reproduction, which is a necessary part of ensuring the survival of society.

Once children are produced, the family plays a vital role in training them for adult life. As the primary agent of socialization and enculturation, the family teaches young children the ways of thinking and behaving that follow social and cultural norms, values, beliefs, and attitudes. Parents teach their children manners and civility. A well-mannered child reflects a well-mannered parent.

Parents also teach children gender roles. Gender roles are an important part of the economic function of a family. In each family, there is a division of labor that consists of instrumental and expressive roles. Men tend to assume the instrumental roles in the family, which typically involve work outside of the family that provides financial support and establishes family status. Women tend to assume the expressive roles, which typically involve work inside of the family which provides emotional support and physical care for children (Crano and Aronoff 1978). According to functionalists, the differentiation of the roles on the basis of sex ensures that families are well balanced and coordinated. When family members move outside of these roles, the family is thrown out of balance and must recalibrate in order to function properly. For example, if the father assumes an expressive role such as providing daytime care for the children, the mother must take on an instrumental role such as gaining paid employment outside of the home in order for the family to maintain balance and function.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists are quick to point out that U.S. families have been defined as private entities, the consequence of which has been to leave family matters to only those within the family. Many people in the United States are resistant to government intervention in the family: parents do not want the government to tell them how to raise their children or to become involved in domestic issues. Conflict theory highlights the role of power in family life and contends that the family is often not a haven but rather an arena where power struggles can occur. This exercise of power often entails the performance of family status roles. Conflict theorists may study conflicts as simple as the enforcement of rules from parent to child, or they may examine more serious issues such as domestic violence (spousal and child), sexual assault, marital rape, and incest.

The first study of marital power was performed in 1960. Researchers found that the person with the most access to value resources held the most power. As money is one of the most valuable resources, men who worked in paid labor outside of the home held more power than women who worked inside the home (Blood and Wolfe 1960). Conflict theorists find disputes over the division of household labor to be a common source of marital discord. Household labor offers no wages and, therefore, no power. Studies indicate that when men do more housework, women experience more satisfaction in their marriages, reducing the incidence of conflict (Coltrane 2000). In general, conflict theorists tend to study areas of marriage and life that involve inequalities or discrepancies in power and authority, as they are reflective of the larger social structure.

Symbolic Interactionism

Interactionists view the world in terms of symbols and the meanings assigned to them (LaRossa and Reitzes 1993). The family itself is a symbol. To some, it is a father, mother, and children; to others, it is any union that involves respect and compassion. Interactionists stress that family is not an objective, concrete reality. Like other social phenomena, it is a social construct that is subject to the ebb and flow of social norms and ever-changing meanings.

Consider the meaning of other elements of family: “parent” was a symbol of a biological and emotional connection to a child; with more parent-child relationships developing through adoption, remarriage, or change in guardianship, the word “parent” today is less likely to be associated with a biological connection than with whoever is socially recognized as having the responsibility for a child’s upbringing. Similarly, the terms “mother” and “father” are no longer rigidly associated with the meanings of caregiver and breadwinner. These meanings are more free-flowing through changing family roles.

Interactionists also recognize how the family status roles of each member are socially constructed, playing an important part in how people perceive and interpret social behavior. Interactionists view the family as a group of role players or “actors” that come together to act out their parts in an effort to construct a family. These roles are up for interpretation. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a “good father,” for example, was one who worked hard to provided financial security for his children. Today, a “good father” is one who takes the time outside of work to promote his children’s emotional well-being, social skills, and intellectual growth—in some ways, a much more daunting task.

Summary

People’s concepts of marriage and family in the United States are changing. Increases in cohabitation, same-sex partners, and singlehood are altering of our ideas of marriage. Similarly, single parents, same-sex parents, cohabitating parents, and unwed parents are changing our notion of what it means to be a family. While most children still live in opposite-sex, two-parent, married households, that is no longer viewed as the only type of nuclear family.

Short Answer

Explain the different variations of the nuclear family and the trends that occur in each.

Why are some couples choosing to cohabitate before marriage? What effect does cohabitation have on marriage?

References

Bakalar, Nicholas. 2010. “Education, Faith, and a Likelihood to Wed.” New York Times, March 22. Retrieved February 14, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/23/health/23stat.html).

Biblarz, Tim. J., and Judith Stacey. 2010. “How Does the Gender of Parents Matter?” Journal of Marriage and Family 72:3–22.

Blood, Robert Jr. and Donald Wolfe. 1960. Husbands and Wives: The Dynamics of Married Living. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Coltrane, Scott. 2000. “Research on Household Labor: Modeling and Measuring the Social Embeddedness of Routine Family Work.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 62:1209–1233.

Crano, William, and Joel Aronoff. 1978. “A Cross-Cultural Study of Expressive and Instrumental Role Complementarity in the Family.” American Sociological Review 43:463–471.

De Toledo, Sylvie, and Deborah Edler Brown. 1995. Grandparents as Parents: A Survival Guide for Raising a Second Family. New York: Guilford Press.

Hurley, Dan. 2005. “Divorce Rate: It’s Not as High as You Think.” New York Times, April 19. Retrieved February 14, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/19/health/19divo.html).

Jayson, Sharon. 2010. “Report: Cohabiting Has Little Effect on Marriage Success.” USA Today, October 14. Retrieved February 14, 2012 (http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-03-02-cohabiting02_N.htm).

LaRossa, Ralph, and Donald Reitzes. 1993. “Symbolic Interactionism and Family Studies.” Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. New York: Plenum Press.

Lee, Gary. 1982. Family Structure and Interaction: A Comparative Analysis. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Roberts, Sam. 2007. “51% of Women Are Now Living Without a Spouse.” New York Times, January 16. Retrieved from February 14, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/16/us/16census.html?pagewanted=all0).

U.S. Census Bureau. 1997. “Children With Single Parents – How They Fare.” Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.census.gov/prod/3/97pubs/cb-9701.pdf).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2009. “American Community Survey (ACS).” Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.census.gov/acs/www/).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. “Current Population Survey (CPS).” Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.census.gov/population/www/cps/cpsdef.html).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. “America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. Forum on Child and Family Statistics. Retrieved January 16, 2012 (http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/famsoc1.asp).

Venugopal, Arun. 2011. “New York Leads in Never-Married Women.” WNYC, December 10. Retrieved February 14, 2012 (http://www.wnyc.org/blogs/wnyc-news-blog/2011/sep/22/new-york-never-married-women/).

Waite, Linda, and Lee Lillard. 1991. “Children and Marital Disruption.” American Journal of Sociology 96(4):930–953.

two parents (traditionally a married husband and wife) and children living in the same household

a household that includes at least one parent and child as well as other relatives like grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins