2 Chapter 2: Vectors

Link to online textbook chapter

Khan Academy: Videos about Vectors

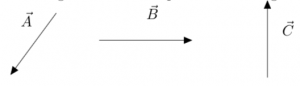

Section 2.1: Scalars vs. Vectors

Link to Section 2.1 of the textbook

A scalar is something you can measure. You have 45 bananas, or it’s 72 degrees in the room, or your tire has 3 holes in it. These are all scalar quantities. Common examples of scalars we will see in this class are distance, speed, temperature, energy, and length. Scalars can be positive or negative, but we’ll usually just see the positive aspect of them in class.

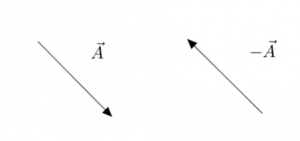

A vector has both term for how much you have of something (called a magnitude) and a direction (where you’re going). Common examples of vectors we’ll see in this class are displacement, velocity, acceleration, and forces.

Vectors are represented by either a line over a variable, ![]() , a bold variable,

, a bold variable, ![]() , or a line under a variable,

, or a line under a variable, ![]() . In physics, we use the notation

. In physics, we use the notation ![]() for vectors, except where the format doesn’t support that option, in which case we’ll use a bold value.

for vectors, except where the format doesn’t support that option, in which case we’ll use a bold value.

The magnitude of a vector is found by removing the directional component. A magnitude is always a positive value. The following notation means to take the magnitude of the vector: ![]() . Note that a vector without direction is simply a scalar value

. Note that a vector without direction is simply a scalar value ![]() .

.

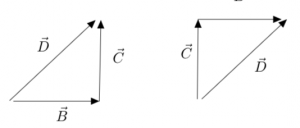

Section 2.2: Graphical Addition of Vectors

Link to Section 2.3 of the textbook

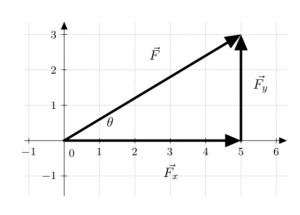

Section 2.3: Component Vectors

Link to Section 2.2 of the textbook

Any vector can be written as the sum of two vectors in any given coordinate system.

In the figure on the right, the vector ![]() can be described as the sum of the vectors

can be described as the sum of the vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . Why would we do this? We are breaking up the vector

. Why would we do this? We are breaking up the vector ![]() into its component vectors in the

into its component vectors in the ![]() coordinate system.

coordinate system. ![]() lies along the

lies along the ![]() -axis, and

-axis, and ![]() lies along the

lies along the ![]() -axis. We can describe a vector pointing in any two dimensional direction using the

-axis. We can describe a vector pointing in any two dimensional direction using the ![]() coordinate system in this manner.

coordinate system in this manner.

We can now write ![]() . Let’s recall some basic geometry. In a right triangle, the Sine of an angle is the side of the triangle Opposite the angle divided by the Hypotenuse of the triangle (SOH). The sine of the angle

. Let’s recall some basic geometry. In a right triangle, the Sine of an angle is the side of the triangle Opposite the angle divided by the Hypotenuse of the triangle (SOH). The sine of the angle ![]() in the figure above is given by sin(

in the figure above is given by sin(![]() ) =

) = ![]() . The Cosine of an angle is given by the Adjacent side to the angle divided by the Hypotenuse. The cosine of

. The Cosine of an angle is given by the Adjacent side to the angle divided by the Hypotenuse. The cosine of ![]() is given by cos(

is given by cos(![]() ) =

) = ![]() (CAH). The Tangent of the angle

(CAH). The Tangent of the angle ![]() is found by dividing the Opposite side by the Adjacent side, tan(

is found by dividing the Opposite side by the Adjacent side, tan(![]() ) =

) = ![]() (TOA). Thus, the abbreviation SOH CAH TOA.

(TOA). Thus, the abbreviation SOH CAH TOA.

Note that the system above depends on which angle you call ![]() . Every time you try to solve a vector graphically in this manner, you must draw a picture and indicate which angle is which.

. Every time you try to solve a vector graphically in this manner, you must draw a picture and indicate which angle is which.

By rearranging the above equations, we can come to the conclusion that ![]() sin(

sin(![]() ) and

) and ![]() cos(

cos(![]() ). Now we can write the vector

). Now we can write the vector ![]() as the sum of its component vectors expressed as functions of

as the sum of its component vectors expressed as functions of ![]() ,

, ![]() sin(

sin(![]() ) +

) + ![]() cos(

cos(![]() ).

).

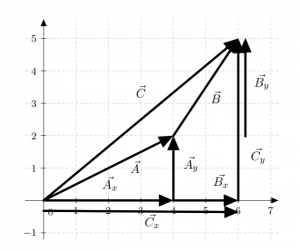

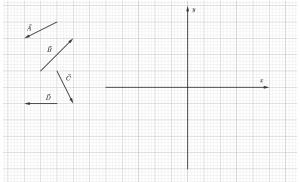

The figure to the left illustrates the components of the sum of vectors ![]() . Vectors

. Vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() have been broken into their components, where

have been broken into their components, where ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Vectors

. Vectors ![]() and

and ![]() have been slightly offset from their positions for clarity.

have been slightly offset from their positions for clarity.

Above, ![]() . However, since

. However, since ![]() , and

, and ![]() , we can also write this as

, we can also write this as ![]() , or, grouping

, or, grouping ![]() and

and ![]() terms,

terms,

![]()

and we can conclude that

![]()

![]()

What does this mean? Look at the figure above. The ![]() component of

component of ![]() is made up of the sum of the

is made up of the sum of the ![]() components of

components of ![]() and

and ![]() . The same is true for the

. The same is true for the ![]() components.

components.

We have defined ![]() . Does this also mean that

. Does this also mean that ![]() ? In other words, can you add the magnitudes of the vectors and come up with the same result as if you added the vectors themselves? The answer is no. Adding the vectors means adding

? In other words, can you add the magnitudes of the vectors and come up with the same result as if you added the vectors themselves? The answer is no. Adding the vectors means adding ![]() and

and ![]() , both of which include directional information. In terms of a path to take, adding the vectors is the equivalent of going from the origin to the tip of the

, both of which include directional information. In terms of a path to take, adding the vectors is the equivalent of going from the origin to the tip of the ![]() arrow directly. Adding only the magnitudes adds the numbers with no directional information included. In terms of a path, adding the magnitudes only is equivalent to going from the origin to the tip of

arrow directly. Adding only the magnitudes adds the numbers with no directional information included. In terms of a path, adding the magnitudes only is equivalent to going from the origin to the tip of ![]() , the continuing from there to the tip of

, the continuing from there to the tip of ![]() . Is this the same path? No, the second path was longer. In fact, the only case where adding the vectors is equivalent to adding the magnitudes is the case in which all vectors are pointing in the same direction. So we have concluded that

. Is this the same path? No, the second path was longer. In fact, the only case where adding the vectors is equivalent to adding the magnitudes is the case in which all vectors are pointing in the same direction. So we have concluded that ![]() .

.

When adding vectors, you must add their ![]() and

and ![]() components separately. You cannot directly add two numbers that point in different directions and expect to get an answer that makes sense.

components separately. You cannot directly add two numbers that point in different directions and expect to get an answer that makes sense.

Section 2.4: Unit Vectors

Link to Section 2.2 of the textbook

A unit vector, denoted with a hat (![]() ), is a vector with some direction and a magnitude of 1. The job of a unit vector is simply to point in some direction. What we’ll normally use it for is pointing in either the

), is a vector with some direction and a magnitude of 1. The job of a unit vector is simply to point in some direction. What we’ll normally use it for is pointing in either the ![]() or

or ![]() directions, along the axes of our coordinate system. As we’ve already seen, any vector that can be drawn in the

directions, along the axes of our coordinate system. As we’ve already seen, any vector that can be drawn in the ![]() coordinate system can be reduced to two vectors, one pointing along

coordinate system can be reduced to two vectors, one pointing along ![]() and one pointing along

and one pointing along ![]() . Why are we breaking up our vectors in this manner? Because if we want to do math with vectors, we can only add/subtract vectors pointing in the same direction.

. Why are we breaking up our vectors in this manner? Because if we want to do math with vectors, we can only add/subtract vectors pointing in the same direction. ![]() and

and ![]() are the most convenient directions for us to use.

are the most convenient directions for us to use.

The unit vectors used for the three dimensional coordinate system pointing along ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are

are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

. ![]() means you’re pointing in the

means you’re pointing in the ![]() direction,

direction, ![]() is for the

is for the ![]() direction, and

direction, and ![]() means the

means the ![]() direction.

direction.

We can use our unit vectors to re-write our normal definition of a vector with components, ![]() , as

, as

![]()

where ![]() is the magnitude of

is the magnitude of ![]() and

and ![]() is the magnitude of

is the magnitude of ![]() . As long as we’re using the unit vectors, we only need the magnitudes of the components. The unit vector tells us the direction.

. As long as we’re using the unit vectors, we only need the magnitudes of the components. The unit vector tells us the direction.

We can also re-write our previous equation from a bit earlier

![]()

as

![]()

using our unit vector notation.

Section 2.5: Mathematical Vector Addition

Link to Section 2.3 of the textbook

We’ve already seen how to add vectors graphically. What about adding them numerically? Let’s say we were given two vectors to add, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . What would these vectors look like?

. What would these vectors look like?

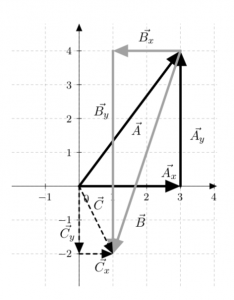

In the figure on the right, we show the graphical addition of ![]() . We begin by placing

. We begin by placing ![]() (solid black lines) at the origin, going over 3 units to the right (3

(solid black lines) at the origin, going over 3 units to the right (3 ![]() ) and 4 units up (4

) and 4 units up (4 ![]() ). Starting from the tip of

). Starting from the tip of ![]() , we now add in

, we now add in ![]() (solid grey lines) by moving 2 units left (-2

(solid grey lines) by moving 2 units left (-2 ![]() ) and then 6 units down (-6

) and then 6 units down (-6 ![]() ). The resulting vector sum

). The resulting vector sum ![]() (dotted black lines) points from the beginning of

(dotted black lines) points from the beginning of ![]() at the origin to the tip of

at the origin to the tip of ![]() . The components of

. The components of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are all given.

are all given.

Based on this graphical picture, we would expect the vector sum ![]() to correspond to 1 unit to the left and 2 units down (from the tail of the first vector to the head of the last vector), or

to correspond to 1 unit to the left and 2 units down (from the tail of the first vector to the head of the last vector), or ![]() . How can we find this numerically?

. How can we find this numerically?

To add vectors mathematically, we add the ![]() components and the

components and the ![]() components separately.

components separately. ![]() , and

, and ![]() , so we know that

, so we know that ![]() = 3,

= 3, ![]() = 4,

= 4, ![]() = -2, and

= -2, and ![]() = -6. Using a previous equation, we see that

= -6. Using a previous equation, we see that ![]() , or

, or ![]() , and

, and ![]() , or

, or ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

Now we know the ![]() and

and ![]() components of our resulting vector

components of our resulting vector ![]() . What if we wanted to know the length (magnitude) of

. What if we wanted to know the length (magnitude) of ![]() ? This is the same thing as finding the hypotenuse of a triangle made up of sides

? This is the same thing as finding the hypotenuse of a triangle made up of sides ![]() and

and ![]() . We use Pythagorean’s Theorem (

. We use Pythagorean’s Theorem (![]() ) to find the length of the third side. This is also called finding the magnitude of

) to find the length of the third side. This is also called finding the magnitude of ![]() (it does not supply us with the direction). To find the \emph{magnitude} of a vector,

(it does not supply us with the direction). To find the \emph{magnitude} of a vector, ![]() ,

,

![]()

So we see that in this case, ![]() . This is the length of

. This is the length of ![]() in the figure on the previous page.

in the figure on the previous page.

Now that we’ve found the magnitude of ![]() , how do we find the direction? The direction is given by the angle from a particular direction. The angle can be found using any of our trig functions now that we know the values of all three sides of the triangle. Working with only

, how do we find the direction? The direction is given by the angle from a particular direction. The angle can be found using any of our trig functions now that we know the values of all three sides of the triangle. Working with only ![]() and

and ![]() , we can see that tan(

, we can see that tan(![]() ) =

) = ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the angle between

is the angle between ![]() and the

and the ![]() axis. That means that

axis. That means that ![]() = tan

= tan![]() , or

, or ![]() = tan

= tan![]() east of south. That last part means starting from south (negative

east of south. That last part means starting from south (negative ![]() axis) move 26.6

axis) move 26.6![]() degrees towards the east direction (positive

degrees towards the east direction (positive ![]() axis). Ignore any negative signs when calculating the angles and instead indicate direction by using the angle (in the 0

axis). Ignore any negative signs when calculating the angles and instead indicate direction by using the angle (in the 0![]() to 90

to 90![]() range) and the cardinal directions north, east, south, and west.

range) and the cardinal directions north, east, south, and west.

Convince yourself that ![]() using the vectors given in the previous example.

using the vectors given in the previous example.

In Class Group Work Problems 2.1, 2.2, 2.3

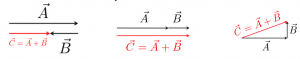

2.1 Given the two vectors on the left, which of the three graphical additions on the right are equal to ![]() ?

?

2.2 Could you change the equation to make another graphical addition correct?

2.3 Is there a way to change the equation to get the remaining graphical addition to be the correct answer?

In Class Group Work Problems 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6

2.4 Find vector ![]() in

in ![]() notation if

notation if ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

2.5 Calculate the angle between ![]() and the positive

and the positive ![]() -axis.

-axis.

2.6 Calculate the angle between ![]() and the positive

and the positive ![]() -axis.

-axis.

In Class Group Work Problem 2.7

2.7 Vector ![]() . Find the magnitude and directions of

. Find the magnitude and directions of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

In Class Group Work Problem 2.8

2.8 Vector ![]() is made up of components

is made up of components ![]() and

and ![]() . Find the magnitude and direction of

. Find the magnitude and direction of ![]() .

.

Previous Exam Question 1

These questions are provided for practice purposes. There is no guarantee a problem similar to this one will be on your exam.

Given the vectors and axes, draw the graphical addition of ![]() .

.

Write the vector ![]() you graphed in the previous question in

you graphed in the previous question in ![]() form.

form.

Calculate the magnitude of the vector ![]() you found in the previous questions.

you found in the previous questions.

Previous Exam Question 2

These questions are provided for practice purposes. There is no guarantee a problem similar to this one will be on your exam.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Find the resultant vector ![]() in

in ![]() form if

form if ![]() .

.

Previous Exam Question 3

These questions are provided for practice purposes. There is no guarantee a problem similar to this one will be on your exam.

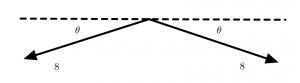

Two vectors each have a magnitude of 8 units and each vector makes a small angle ![]() with the horizontal as shown below. Four students are arguing about the resultant vector obtained by adding these two vectors.

with the horizontal as shown below. Four students are arguing about the resultant vector obtained by adding these two vectors.

Amanda: “Since these are vectors, we need to use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the magnitude. In this case, the magnitude should be the square root of 128. The direction should be downward.”

Do you agree with Amanda? Why or why not, and on which statements?

Belle: “Since these are vectors, we have to find a direction and a magnitude. We use the vectors to determine the direction, which is down. But to get the magnitude, we just add the individual magnitudes. The magnitude of the resultant vector is sixteen.”

Do you agree with Belle? Why or why not, and on which statements?

Conrad: “I think the direction is actually up. The resultant should add to these vectors to get zero, and since these ones point down, we need another vector pointing up.”

Do you agree with Conrad? Why or why not, and on which statements?

Douglas: “The magnitude will be less than eight. Each of these point down just a little so the resultant will be pretty small.”

Do you agree with Douglas? Why or why not, and on which statements?

A quantity that has a magnitude (how much you have) but no associated direction.

A quantity that has both a magnitude (how much you have) and a direction (where you're going).

How much of something you have. Magnitude can also refer to the absolute value of a vector.

The part of the vector that indicates where the object is going.

Any vector can be broken into components in a given coordinate system. Typically, we break a vector into x and y components.

A vector with a magnitude of 1 whose only job is to point in some direction. The unit vector that points in the x-direction is called i, the unit vector that points in the y-direction is called j, and the unit vector that points in the z-direction is called k.