Chapter 14. DNA Replication

Chapter Outline

- 14.1 Historical Basis of Modern Understanding

- 14.2 Overview of DNA Replication

- 14.3 DNA Replication in Prokaryotes

- 14.4 DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

- 14.5 DNA Repair

Introduction

The three letters “DNA” have now become synonymous with crime solving, paternity testing, human identification, and genetic testing. DNA can be retrieved from hair, blood, or saliva. Each person’s DNA is unique, and it is possible to detect differences between individuals within a species on the basis of these unique features. DNA analysis has many practical applications beyond forensics. In humans, DNA testing is applied to numerous uses: tracing genealogy, identifying pathogens, archeological research, tracing disease outbreaks, and studying human migration patterns. In the medical field, DNA is used in diagnostics, new vaccine development, and cancer therapy. It is now possible to determine predisposition to diseases by looking at genes.

Each human cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes: one set of chromosomes is inherited from the mother and the other set is inherited from the father. There is also a mitochondrial genome, inherited exclusively from the mother, which can be involved in inherited genetic disorders. On each chromosome, there are thousands of genes, sequences of DNA that code for a functional product, that are responsible for determining the genotype and phenotype of the individual. The human haploid genome contains 3 billion base pairs and has between 20,000 and 25,000 functional genes.

In order for DNA to serve its role as the genetic material, all organisms must be able to faithfully copy the entire genome. This process, DNA replication, is the precursor to all forms of cell division.

14.1 | Historical Basis of Modern Understanding

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain transformation of DNA.

- Describe the key experiments that helped identify that DNA is the genetic material.

- State and explain Chargaff’s rules

Modern understandings of DNA have evolved from the discovery of nucleic acids to the development of the double-helix model. In the 1860s, Friedrich Miescher (Figure 14.2), a physician by profession, was the first person to isolate phosphate- rich chemicals from white blood cells or leukocytes. He named these chemicals (which would eventually be known as RNA and DNA) nuclein because they were isolated from the nuclei of the cells.

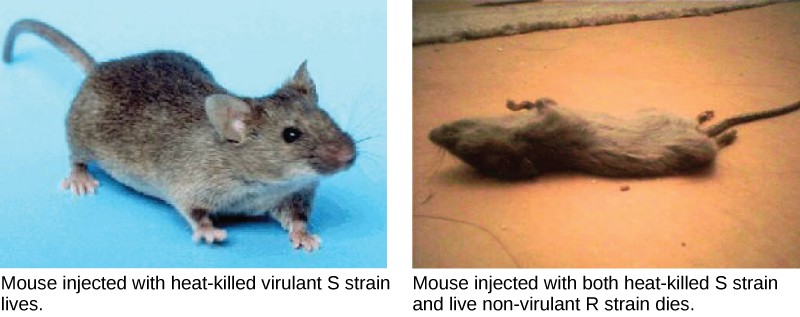

A half century later, British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith was perhaps the first person to show that hereditary information could be transferred from one cell to another “horizontally,” rather than by descent. In 1928, he reported the first demonstration of bacterial transformation, a process in which external DNA is taken up by a cell, thereby changing morphology and physiology. He was working with Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacterium that causes pneumonia. Griffith worked with two strains, rough (R) and smooth (S). The R strain is non-pathogenic (does not cause disease) and is called rough because its outer surface is a cell wall and lacks a capsule; as a result, the cell surface appears uneven under the microscope. The S strain is pathogenic (disease-causing) and has a capsule outside its cell wall. As a result, it has a smooth appearance under the microscope. Griffith injected the live R strain into mice and they survived. In another experiment, when he injected mice with the heat-killed S strain, they also survived. In a third set of experiments, a mixture of live R strain and heat-killed S strain were injected into mice, and—to his surprise—the mice died. Upon isolating the live bacteria from the dead mouse, only the S strain of bacteria was recovered. When this isolated S strain was injected into fresh mice, the mice died. Griffith concluded that something had passed from the heat-killed S strain into the live R strain and transformed it into the pathogenic S strain, and he called this the transforming principle (Figure 11.3). These experiments are now famously known as Griffith’s transformation experiments.

Scientists Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty (1944) were interested in exploring this transforming principle further. They isolated the S strain from the dead mice and isolated the proteins and nucleic acids, namely RNA and DNA, as these were possible candidates for the molecule of heredity. They conducted a systematic elimination study. They used enzymes that specifically degraded each component and then used each mixture separately to transform the R strain. They found that when DNA was degraded, the resulting mixture was no longer able to transform the bacteria, whereas all of the other combinations were able to transform the bacteria. This led them to conclude that DNA was the transforming principle.

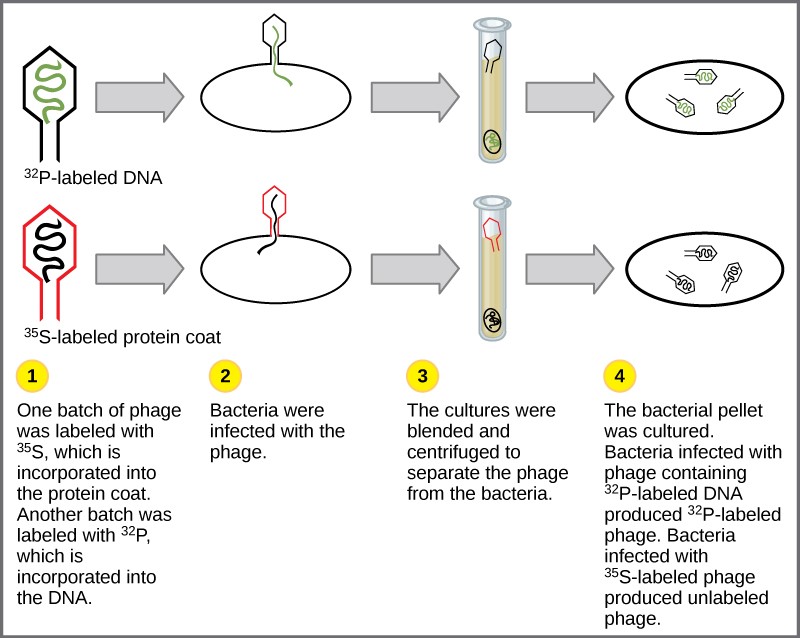

Experiments conducted by Martha Chase and Alfred Hershey in 1952 provided confirmatory evidence that DNA was the genetic material and not proteins. Chase and Hershey were studying a bacteriophage, which is a virus that infects bacteria. Viruses typically have a simple structure: a protein coat, called the capsid, and a nucleic acid core that contains the genetic material, either DNA or RNA. The bacteriophage infects the host bacterial cell by attaching to its surface, and then it injects its nucleic acids inside the cell. The phage DNA makes multiple copies of itself using the host machinery, and eventually the host cell bursts, releasing a large number of bacteriophages. Hershey and Chase labeled one batch of phage with radioactive sulfur, 35S, to label the protein coat. Another batch of phage were labeled with radioactive phosphorus, 32P. Because phosphorous is found in DNA, but not protein, the DNA and not the protein would be tagged with radioactive phosphorus.

Each batch of phage was allowed to infect the cells separately. After infection, the phage bacterial suspension was put in a blender, which caused the phage coat to be detached from the host cell. The phage and bacterial suspension was spun down in a centrifuge. The heavier bacterial cells settled down and formed a pellet, whereas the lighter phage particles stayed in the supernatant (the liquid above the pellet). In the tube that contained phage labeled with 35S, the supernatant contained the radioactively labeled phage, whereas no radioactivity was detected in the pellet. In the tube that contained the phage labeled with 32P, the radioactivity was detected in the pellet that contained the heavier bacterial cells, and no radioactivity was detected in the supernatant. Hershey and Chase concluded that it was the phage DNA that was injected into the cell and carried information to produce more phage particles, thus providing evidence that DNA was the genetic material and not proteins (Figure 14.4).

Around this same time, Austrian biochemist Erwin Chargaff examined the content of DNA in different species and found that the amounts of adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine were not found in equal quantities, and that it varied from species to species, but not between individuals of the same species. He found that the amount of adenine equals the amount of thymine, and the amount of cytosine equals the amount of guanine, or A = T and G = C. These are also known as Chargaff’s rules. This finding proved immensely useful when Watson and Crick were getting ready to propose their DNA double helix model, discussed in Chapter 5.

14.2 | Overview of DNA Replication

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how the structure of DNA reveals the replication process.

- Describe the Meselson and Stahl experiments.

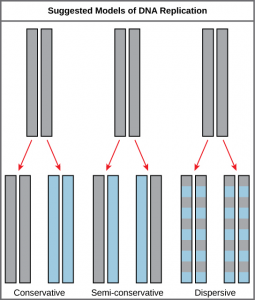

The elucidation of the structure of the double helix provided a hint as to how DNA divides and makes copies of itself. This model suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. What was not clear was how the replication took place. There were three models suggested (Figure 14.5): conservative, semi-conservative, and dispersive.

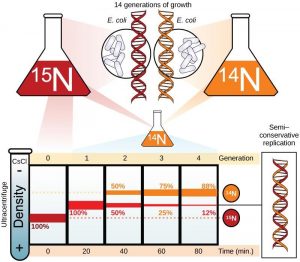

In conservative replication, the parental DNA remains together, and the newly formed daughter strands are together. The semi-conservative method suggests that each of the two parental DNA strands act as a template for new DNA to be synthesized; after replication, each double-stranded DNA includes one parental or “old” strand and one “new” strand. In the dispersive model, both copies of DNA have double-stranded segments of parental DNA and newly synthesized DNA interspersed. Meselson and Stahl were interested in understanding how DNA replicates. They grew E. coli for several generations in a medium containing a “heavy” isotope of nitrogen (15N) that gets incorporated into nitrogenous bases, and eventually into the DNA (Figure 14.6).

The E. coli culture was then shifted into medium containing 14N and allowed to grow for one generation. The cells were harvested and the DNA was isolated. The DNA was centrifuged at high speeds in an ultracentrifuge. Some cells were allowed to grow for one more life cycle in 14N and spun again. During the density graditent centrifugation, the DNA is loaded into a gradient (typically a salt such as cesium chloride or sucrose) and spun at high speeds of 50,000 to 60,000 rpm. Under these circumstances, the DNA will form a band according to its density in the gradient. DNA grown in 15N will band at a higher density position than that grown in 14N. Meselson and Stahl noted that after one generation of growth in 14N after they had been shifted from 15N, the single band observed was intermediate in position in between DNA of cells grown exclusively in 15N and 14N. This suggested either a semi-conservative or dispersive mode of replication. The DNA harvested from cells grown for two generations in 14N formed two bands: one DNA band was at the intermediate position, between 15N and 14N and the other corresponded to the band of 14N DNA. These results could only be explained if DNA replicates in a semi-conservative manner. Therefore, the other two modes were ruled out.

During DNA replication, each of the two strands that make up the double helix serves as a template from which new strands are copied. The new strand will be complementary to the parental or “old” strand. When two daughter DNA copies are formed, they have the same sequence and are divided equally into the two daughter cells.

14.3 | DNA Replication in Prokaryotes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the process of DNA replication in prokaryotes.

- Discuss the role of different enzymes and proteins in supporting this process.

DNA replication has been extremely well studied in prokaryotes primarily because of the small size of the genome and the mutants that are available. E. coli has 4.6 million base pairs in a single circular chromosome and all of it gets replicated in approximately 42 minutes, starting from a single origin of replication and proceeding around the circle in both directions. This means that approximately 1000 nucleotides are added per second. The process is quite rapid and occurs without many mistakes.

DNA replication employs a large number of proteins and enzymes, each of which plays a critical role during the process. One of the key players is the enzyme DNA polymerase, also known as DNA pol, which adds nucleotides one by one to the growing DNA chain that are complementary to the template strand. The addition of nucleotides requires energy; this energy is obtained from the nucleotides that have three phosphates attached to them, similar to ATP which has three phosphate groups attached. When the bond between the phosphates is broken, the energy released is used to form the phosphodiester bond between the incoming nucleotide and the growing chain. In prokaryotes, three main types of polymerases are known: DNA pol I, DNA pol II, and DNA pol III. It is now known that DNA pol III is the enzyme required for DNA synthesis; DNA pol I and DNA pol II are primarily required for repair.

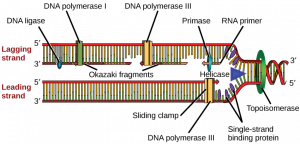

How does the replication machinery know where to begin? It turns out that there are specific nucleotide sequences called origins of replication where replication begins. In E. coli, which has a single origin of replication on its one chromosome (as do most prokaryotes), it is approximately 245 base pairs long and is rich in AT sequences. The origin of replication is recognized by certain proteins that bind to this site. An enzyme called helicase unwinds the DNA by breaking the hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous base pairs. ATP hydrolysis is required for this process. As the DNA opens up, Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed. Two replication forks are formed at the origin of replication and these get extended bi- directionally as replication proceeds. Single-strand binding proteins coat the single strands of DNA near the replication fork to prevent the single-stranded DNA from winding back into a double helix. DNA polymerase is able to add nucleotides only in the 5′ to 3′ direction (a new DNA strand can be only extended in this direction). It also requires a free 3′- OH group to which it can add nucleotides by forming a phosphodiester bond between the 3′-OH end and the 5′ phosphate of the next nucleotide. This essentially means that it cannot add nucleotides if a free 3′-OH group is not available. Then how does it add the first nucleotide? The problem is solved with the help of a primer that provides the free 3′-OH end. Another enzyme, RNA primase, synthesizes an RNA primer that is about five to ten nucleotides long and complementary to the DNA. Because this sequence primes the DNA synthesis, it is appropriately called the primer. DNA polymerase can now extend this RNA primer, adding nucleotides one by one that are complementary to the template strand (Figure 14.7).

The replication fork moves at the rate of 1000 nucleotides per second. DNA polymerase can only extend in the 5′ to 3′ direction, which poses a slight problem at the replication fork. As we know, the DNA double helix is anti-parallel; that is, one strand is in the 5′ to 3′ direction and the other is oriented in the 3′ to 5′ direction. One strand, which is complementary to the 3′ to 5′ parental DNA strand, is synthesized continuously towards the replication fork because the polymerase can add nucleotides in this direction. This continuously synthesized strand is known as the leading strand. The other strand, complementary to the 5′ to 3′ parental DNA, is extended away from the replication fork, in small fragments known as Okazaki fragments, each requiring a primer to start the synthesis. Okazaki fragments are named after the Japanese scientist who first discovered them. The strand with the Okazaki fragments is known as the lagging strand.

Concept check

You isolate a cell strain in which the joining together of Okazaki fragments is impaired and suspect that a mutation has occurred in an enzyme found at the replication fork. Which enzyme is most likely to be mutated?

The leading strand can be extended by one primer alone, whereas the lagging strand needs a new primer for each of the short Okazaki fragments. The overall direction of the lagging strand will be 3′ to 5′, and that of the leading strand 5′ to 3′. A protein called the sliding clamp holds the DNA polymerase in place as it continues to add nucleotides. The sliding clamp is a ring-shaped protein that binds to the DNA and holds the polymerase in place. Topoisomerase prevents the over-winding of the DNA double helix ahead of the replication fork as the DNA is opening up; it does so by causing temporary nicks in the DNA helix and then resealing it. As synthesis proceeds, the RNA primers are replaced by DNA. The primers are removed by the exonuclease activity of DNA pol I, and the gaps are filled in by deoxyribonucleotides. The nicks that remain between the newly synthesized DNA (that replaced the RNA primer) and the previously synthesized DNA are sealed by the enzyme DNA ligase that catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester linkage between the 3′-OH end of one nucleotide and the 5′ phosphate end of the other fragment.

Once the chromosome has been completely replicated, the two DNA copies move into two different cells during cell division. The process of DNA replication can be summarized as follows:

- DNA unwinds at the origin of replication.

- Helicase opens up the DNA-forming replication forks; these are extended bidirectionally.

- Single-strand binding proteins coat the DNA around the replication fork to prevent rewinding of the DNA.

- Topoisomerase binds at the region ahead of the replication fork to prevent supercoiling.

- Primase synthesizes RNA primers complementary to the DNA strand.

- DNA polymerase starts adding nucleotides to the 3′-OH end of the primer.

- Elongation of both the lagging and the leading strand continues.

- RNA primers are removed by exonuclease activity.

- Gaps are filled by DNA pol by adding dNTPs.

- The gap between the two DNA fragments is sealed by DNA ligase, which helps in the formation of phosphodiester bonds.

Table 11.1 Prokaryotic DNA replication: enzymes and their functions.

|

Enzyme/Protein |

Specific Function |

|

DNA pol I |

Exonuclease activity removes RNA primer and replaces with newly synthesized DNA |

|

DNA pol II |

Repair function |

|

DNA pol III |

Main enzyme that adds nucleotides in the 5′-3′ direction |

|

Helicase |

Opens the DNA helix by breaking hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous bases |

|

Ligase |

Seals the gaps between the Okazaki fragments to create one continuous DNA strand |

|

Primase |

Synthesizes RNA primers needed to start replication |

|

Sliding Clamp |

Helps to hold the DNA polymerase in place when nucleotides are being added |

|

Topoisomerase |

Helps relieve the stress on DNA when unwinding by causing breaks and then resealing the DNA |

|

Single-strand binding proteins (SSB) |

Binds to single-stranded DNA to avoid DNA rewinding back. |

14.4 | DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the similarities and differences between DNA replication in eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

- State the role of telomerase in DNA replication.

14.4.1 Prokaryote vs. Eukaryote Replication

Eukaryotic genomes are much more complex and larger in size than prokaryotic genomes. The human genome has three billion base pairs per haploid set of chromosomes, and 6 billion base pairs are replicated during the S phase of the cell cycle. There are multiple origins of replication on the eukaryotic chromosome; humans can have up to 100,000 origins of replication. The rate of replication is approximately 100 nucleotides per second, much slower than prokaryotic replication. In yeast, which is a eukaryote, special sequences known as Autonomously Replicating Sequences (ARS) are found on the chromosomes. These are equivalent to the origin of replication in E. coli.

The number of DNA polymerases in eukaryotes is much more than prokaryotes: 14 are known, of which five are known to have major roles during replication and have been well studied. They are known as pol α, pol β, pol γ, pol δ, and pol ε.

The essential steps of replication are the same as in prokaryotes. Before replication can start, the DNA has to be made available as template. Eukaryotic DNA is bound to basic proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. The chromatin (the complex between DNA and proteins) may undergo some chemical modifications, so that the DNA may be able to slide off the proteins or be accessible to the enzymes of the DNA replication machinery. At the origin of replication, a pre-replication complex is made with other initiator proteins. Other proteins are then recruited to start the replication process (Table 11.2).

A helicase using the energy from ATP hydrolysis opens up the DNA helix. Replication forks are formed at each replication origin as the DNA unwinds. The opening of the double helix causes over-winding, or supercoiling, in the DNA ahead of the replication fork. These are resolved with the action of topoisomerases. Primers are formed by the enzyme primase, and using the primer, DNA pol can start synthesis. While the leading strand is continuously synthesized by the enzyme pol δ, the lagging strand is synthesized by pol ε. A sliding clamp protein known as PCNA (Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen) holds the DNA pol in place so that it does not slide off the DNA. RNase H removes the RNA primer, which is then replaced with DNA nucleotides. The Okazaki fragments in the lagging strand are joined together after the replacement of the RNA primers with DNA. The gaps that remain are sealed by DNA ligase, which forms the phosphodiester bond.

Table 11.2 Differences between Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Replication

|

Property |

Prokaryotes |

Eukaryotes |

|

Origin of replication |

Single |

Multiple |

|

Rate of replication |

1000 nucleotides/s |

50 to 100 nucleotides/s |

|

DNA polymerase types |

5 |

14 |

|

Telomerase |

Not present |

Present |

|

RNA primer removal |

DNA pol I |

RNase H |

|

Strand elongation |

DNA pol III |

Pol δ, pol ε |

|

Sliding clamp |

Sliding clamp |

PCNA |

14.4.2 Telomere Replication

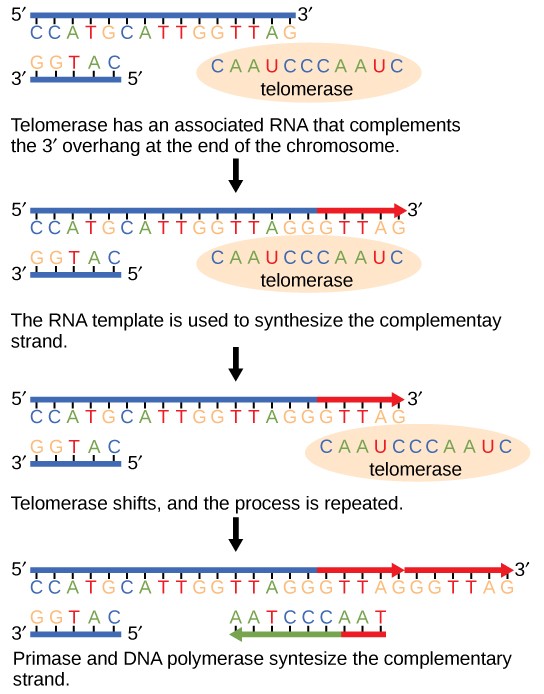

Unlike prokaryotic chromosomes, eukaryotic chromosomes are linear. As you’ve learned, the enzyme DNA pol can add nucleotides only in the 5′ to 3′ direction. In the leading strand, synthesis continues until the end of the chromosome is reached. On the lagging strand, DNA is synthesized in short stretches, each of which is initiated by a separate primer. When the replication fork reaches the end of the linear chromosome, there is no place for a primer to be made for the DNA fragment to be copied at the end of the chromosome. These ends thus remain unpaired, and over time these ends may get progressively shorter as cells continue to divide.

The ends of the linear chromosomes are known as telomeres, which have repetitive sequences that code for no particular gene. In a way, these telomeres protect the genes from getting deleted as cells continue to divide. In humans, a six base pair sequence, TTAGGG, is repeated 100 to 1000 times. The discovery of the enzyme telomerase (Figure 14.8) helped in the understanding of how chromosome ends are maintained. The telomerase enzyme contains a catalytic part and a built-in RNA template. It attaches to the end of the chromosome, and complementary bases to the RNA template are added on the 3′ end of the DNA strand. Once the 3′ end of the lagging strand template is sufficiently elongated, DNA polymerase can add the nucleotides complementary to the ends of the chromosomes. Thus, the ends of the chromosomes are replicated.

Telomerase is typically active in germ cells and adult stem cells. It is not active in adult somatic cells. For her discovery of telomerase and its action, Elizabeth Blackburn (Figure 14.9) received the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 2009.

Telomerase and Aging

Cells that undergo cell division continue to have their telomeres shortened because most somatic cells do not make telomerase. This essentially means that telomere shortening is associated with aging. With the advent of modern medicine, preventative health care, and healthier lifestyles, the human life span has increased, and there is an increasing demand for people to look younger and have a better quality of life as they grow older.

In 2010, scientists found that telomerase can reverse some age-related conditions in mice. This may have potential in regenerative medicine[1]. Telomerase-deficient mice were used in these studies; these mice have tissue atrophy, stem cell depletion, organ system failure, and impaired tissue injury responses. Telomerase reactivation in these mice caused extension of telomeres, reduced DNA damage, reversed neurodegeneration, and improved the function of the testes, spleen, and intestines. Thus, telomere reactivation may have potential for treating age-related diseases in humans.

Cancer is characterized by uncontrolled cell division of abnormal cells. The cells accumulate mutations, proliferate uncontrollably, and can migrate to different parts of the body through a process called metastasis. Scientists have observed that cancerous cells have considerably shortened telomeres and that telomerase is active in these cells. Interestingly, only after the telomeres were shortened in the cancer cells did the telomerase become active. If the action of telomerase in these cells can be inhibited by drugs during cancer therapy, then the cancerous cells could potentially be stopped from further division.

14.5 | DNA Repair

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the different types of mutations in DNA.

- Explain DNA repair mechanisms.

DNA replication is a highly accurate process, but mistakes can occasionally occur, such as a DNA polymerase inserting a wrong base. Uncorrected mistakes may sometimes lead to serious consequences, such as cancer. Repair mechanisms correct the mistakes. In rare cases, mistakes are not corrected, leading to mutations; in other cases, repair enzymes are themselves mutated or defective.

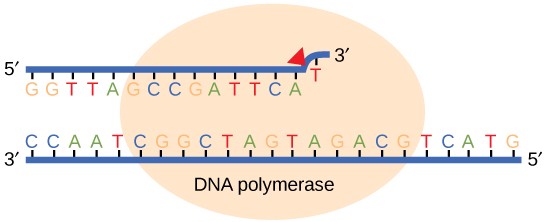

Most of the mistakes during DNA replication are promptly corrected by DNA polymerase by proofreading the base that has been just added (Figure 14.10). In proofreading, the DNA pol reads the newly added base before adding the next one, so a correction can be made. The polymerase checks whether the newly added base has paired correctly with the base in the template strand. If it is the right base, the next nucleotide is added. If an incorrect base has been added, the enzyme makes a cut at the phosphodiester bond and releases the wrong nucleotide. This is performed by the exonuclease action of DNA pol III. Once the incorrect nucleotide has been removed, a new one will be added again.

Some errors are not corrected during replication, but are instead corrected after replication is completed; this type of repair is known as mismatch repair (Figure 14.11). The enzymes recognize the incorrectly added nucleotide and excise it; this is then replaced by the correct base. If this remains uncorrected, it may lead to more permanent damage. How do mismatch repair enzymes recognize which of the two bases is the incorrect one? In E. coli, after replication, the nitrogenous base adenine acquires a methyl group; the parental DNA strand will have methyl groups, whereas the newly synthesized strand lacks them. Thus, DNA polymerase is able to remove the wrongly incorporated bases from the newly synthesized, non- methylated strand. In eukaryotes, the mechanism is not very well understood, but it is believed to involve recognition of unsealed nicks in the new strand, as well as a short-term continuing association of some of the replication proteins with the new daughter strand after replication has completed.

In another type of repair mechanism, nucleotide excision repair, enzymes replace incorrect bases by making a cut on both the 3′ and 5′ ends of the incorrect base (Figure 14.12). The segment of DNA is removed and replaced with the correctly paired nucleotides by the action of DNA pol. Once the bases are filled in, the remaining gap is sealed with a phosphodiester linkage catalyzed by DNA ligase. This repair mechanism is often employed when UV exposure causes the formation of pyrimidine dimers.

A well-studied example of mistakes not being corrected is seen in people suffering from xeroderma pigmentosa (Figure 14.13). Affected individuals have skin that is highly sensitive to UV rays from the sun. When individuals are exposed to UV, pyrimidine dimers, especially those of thymine, are formed; people with xeroderma pigmentosa are not able to repair the damage. These are not repaired because of a defect in the nucleotide excision repair enzymes, whereas in normal individuals, the thymine dimers are excised and the defect is corrected. The thymine dimers distort the structure of the DNA double helix, and this may cause problems during DNA replication. People with xeroderma pigmentosa may have a higher risk of contracting skin cancer than those who dont have the condition.

Errors during DNA replication are not the only reason why mutations arise in DNA. Mutations, variations in the nucleotide sequence of a genome, can also occur because of damage to DNA. Such mutations may be of two types: induced or spontaneous. Induced mutations are those that result from an exposure to chemicals, UV rays, x-rays, or some other environmental agent. Spontaneous mutations occur without any exposure to any environmental agent; they are a result of natural reactions taking place within the body.

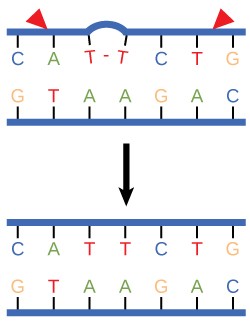

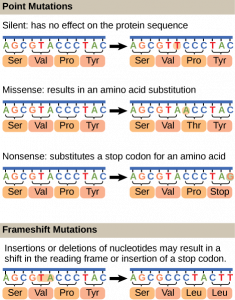

Mutations may have a wide range of effects. Some mutations are not expressed; these are known as silent mutations. Point mutations are those mutations that affect a single base pair. The most common nucleotide mutations are substitutions, in which one base is replaced by another. These can be of two types, either transitions or transversions. Transition substitution refers to a purine or pyrimidine being replaced by a base of the same kind; for example, a purine such as adenine may be replaced by the purine guanine. Transversion substitution refers to a purine being replaced by a pyrimidine, or vice versa; for example, cytosine, a pyrimidine, is replaced by adenine, a purine. Mutations can also be the result of the addition of a base, known as an insertion, or the removal of a base, also known as deletion. Sometimes a piece of DNA from one chromosome may get translocated to another chromosome or to another region of the same chromosome; this is also known as translocation. Some of these mutation types are shown in Figure 14.14.

Mutations in repair genes have been known to cause cancer. Many mutated repair genes have been implicated in certain forms of pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and colorectal cancer. Mutations can affect either somatic cells or germ cells. If many mutations accumulate in a somatic cell, they may lead to problems such as the uncontrolled cell division observed in cancer. If a mutation takes place in germ cells, the mutation will be passed on to the next generation, as in the case of hemophilia and xeroderma pigmentosa.

- Jaskelioff et al., “Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice,” Nature 469 (2011): 102-7. ↵