Large waves crashing onto a shore bring a tremendous amount of energy that has a significant eroding effect, and several unique erosion features commonly form on rocky shores with strong waves.

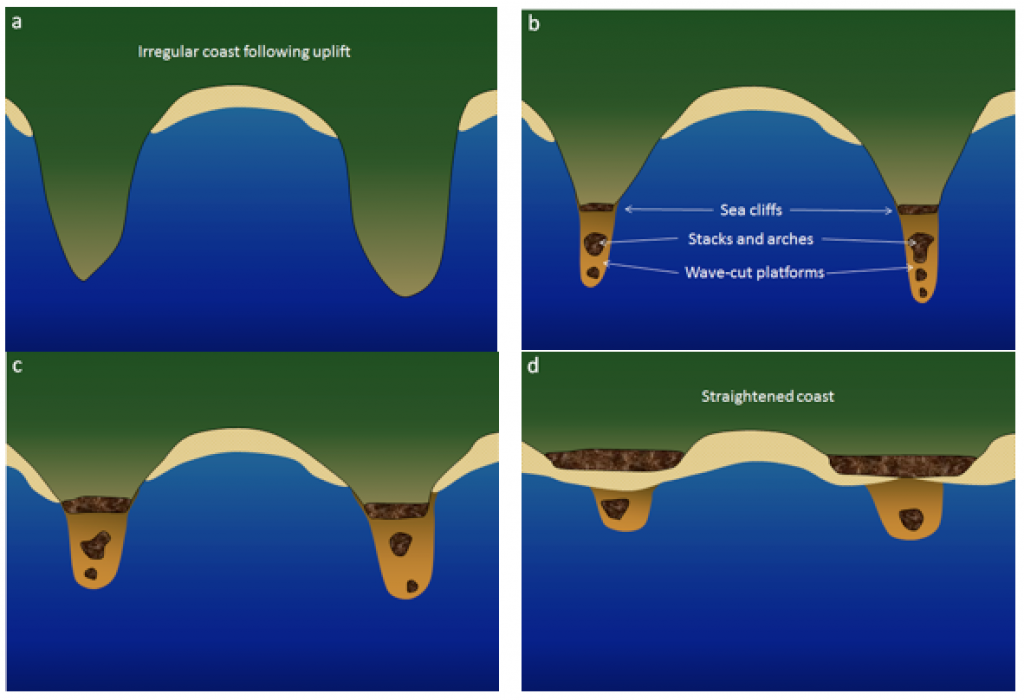

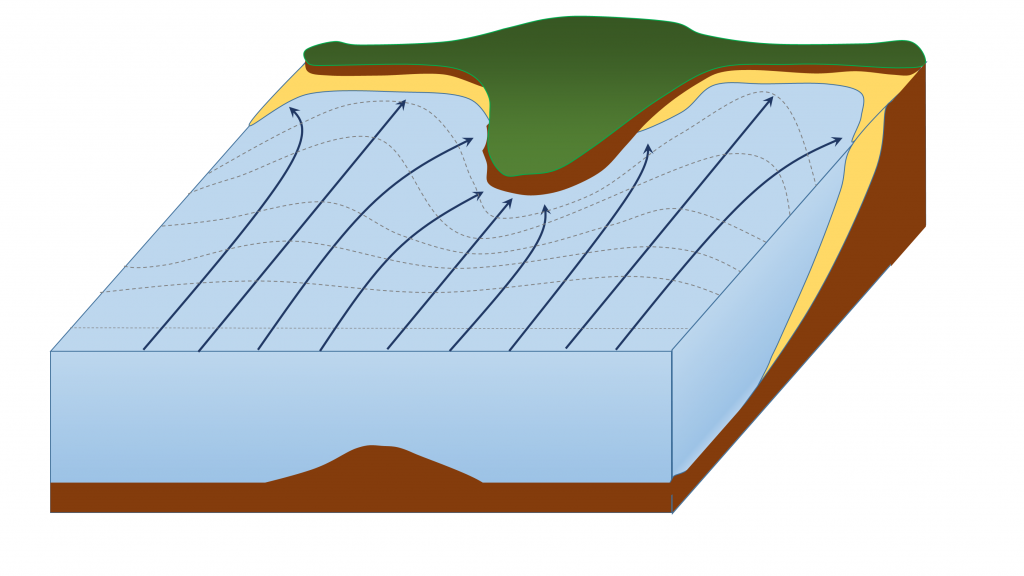

When waves approach an irregular shore, they are slowed down to varying degrees, depending on differences in the water depth, and as they slow, they are bent or refracted (section 10.3). In Figure 13.3.1, wave energy is represented by the blue arrows. That energy is evenly spaced out in the deep water, but because of refraction, the energy of the waves is being focused on the headlands. On irregular coasts, the headlands receive much more wave energy than the intervening bays, and thus they are more strongly eroded. The result of this is coastal straightening, where an irregular coast will eventually become straightened, although that process may take millions of years.

Wave erosion is greatest in the surf zone, where the wave base is impinging strongly on the seafloor and where the waves are breaking. The result is that the substrate in the surf zone is typically eroded to a flat surface known as a wave-cut platform (or wave-cut terrace) (Figure 13.3.2). A wave-cut platform extends across the intertidal zone.

Arches and sea caves form as a result of the erosion of relatively non-resistant rock. Wave action and strong longshore currents can carve a cave into a headland, and if the erosion extends all the way through, it becomes an arch. If a hole develops in the ceiling of a cave, a blowhole can be created, shooting water into the air when waves crash in the cave. An arch in the Barachois River area of western Newfoundland, Canada, is shown in Figure 13.3.3. This feature started out as a sea cave, and then, after being eroded from both sides, became an arch. During the winter of 2012-2013, the arch collapsed, leaving a small stack at the end of the point.

The tower of rock left behind from a collapsed arch is called a sea stack (Figure 13.3.4). But sea stacks can also form during the formation of wave-cut platforms or other features, when relatively resistant rock that does not get completely eroded remains behind to form the stack.