Chapter 9: Ocean Circulation

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

- identify the major ocean surface currents of the world (i.e. the gyres) and explain how they are formed

- identify the features of the Gulf Stream, including the formation of warm and cold core rings

- explain the development and consequences of the Ekman spiral

- explain geostrophic flow, and how it helps keep the gyres flowing even when wind dies down.

- explain why gyre currents are more intense on the western side of the oceans (western intensification)

- explain the causes behind upwelling and downwelling, and the impacts of these events on primary production

- identify the locations of some of the major upwelling regions on Earth

- explain the causes and effects of ENSO events

- explain Langmuir cells

- explain the processes that drive thermohaline circulation

- interpret a T-S diagram to identify water masses

- identify the major global sites of deep water formation

- identify the major global water masses

- explain how deep water circulates throughout the world ocean

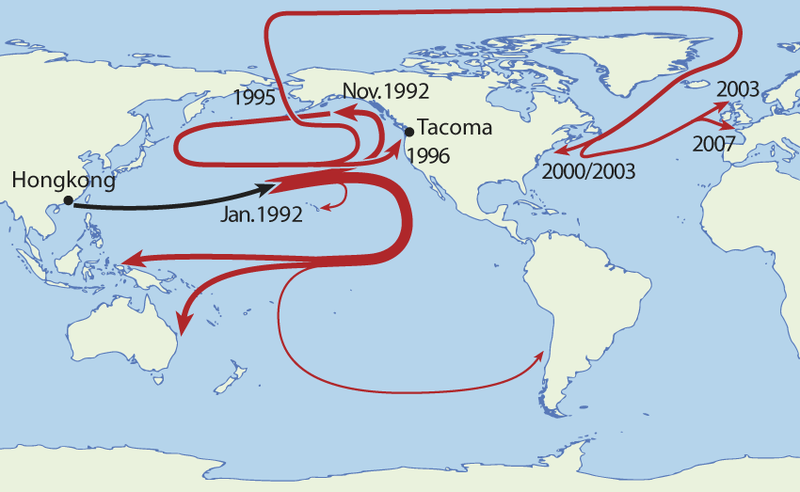

Ocean waters are constantly in motion, from ocean-scale surface currents, to density-driven vertical turnover, to small rotating eddies. Oceanographers have an array of sophisticated tools to measure ocean currents, but from time to time, fortuitous accidents can also aid our understanding of ocean circulation. A great example is the case of the container ship Ever Laurel, which was on its way from Hong Kong to Tacoma, Washington, in January 1992, when 12 containers were washed overboard in a storm in the middle of the Pacific. One of the containers contained over 28,000 plastic bath toys, which were released into the ocean as the container hit the water. Ten months later, the bath toys began washing ashore, first near Sitka, Alaska, then elsewhere along the Alaskan coast, and by 1996, in Washington. Over the next two decades, some toys traveled as far as the Pacific coasts of South America and Australia, while others were found in the Arctic ice, and some even made it through the Arctic into the North Atlantic, washing up in Newfoundland and Scotland (Figure 9.1). There are still a few thousand of the toys floating around in the central North Pacific, and the paths taken by all of these toys have allowed oceanographers to study the movements of large-scale ocean surface currents.